Introduction to Clearing Yard in Chicago

Clearing Yard in Chicago often operates at 1.8 mph, slower than the speed at which an average adult walks. Compound that brutally slow pace with the idea that this same portion of railroad connects six of the seven Class I carriers, and you soon get the feeling somebody has a lot of explaining to do.

One such somebody is Roy Gelder, a 35-year industry veteran and former director of process improvement for The Belt Railway Company of Chicago, operator of Clearing Yard in Chicago, but technically Bedford Park, Ill. On this day, prior to his 2014 retirement, Gelder explains the key to operating a hump yard like Clearing really doesn’t boil down to how fast railcars move. Instead, he says, the success of the operation hinges on consistency and constant throughput.

“You can do the arithmetic quickly: If you’re humping at 1.8 mph, that’s so many feet per second and so many cars per 24 hours,” Gelder says, meaning that, in theory, 9,500 feet of train can be classified, or “humped,” in an hour. “We don’t get close to that simply because we have other things going on at the crest. Better put, the objective is to keep engines moving, always be pushing cars to the hump, and always be ready to go with the next cut when you’re done with the one previous. It’s really about feeding the process, or as some guys will say around here: ‘feeding the Beast.’”

Basics of Clearing Yard

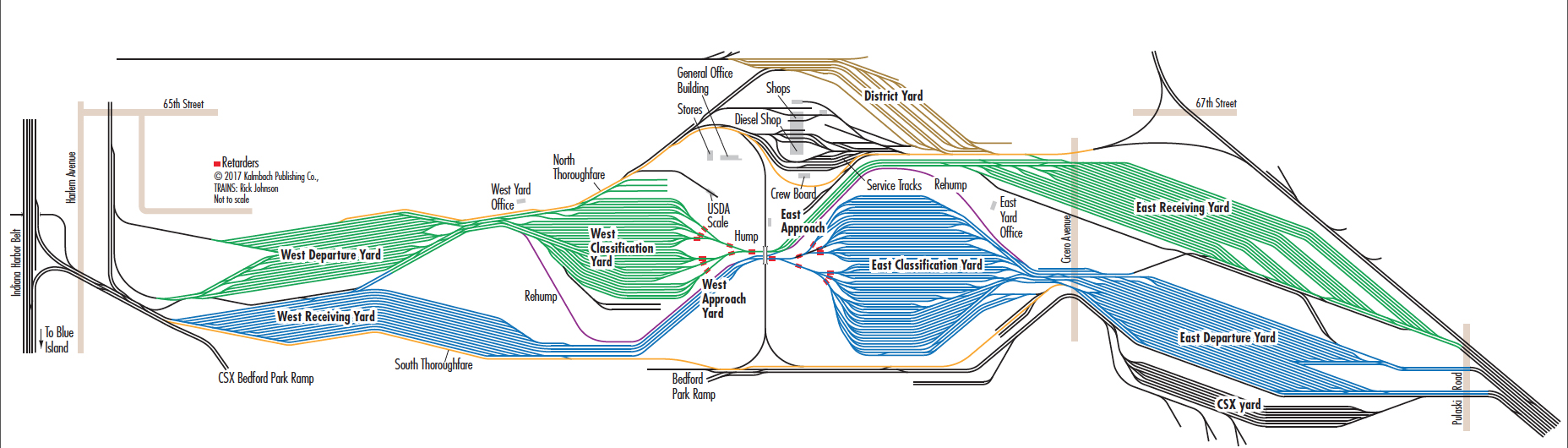

Clearing Yard in Chicago lies about 11 miles southwest of Chicago’s Loop and boasts 350 miles of yard track within 786 acres, making Clearing 15% larger than nearby Midway International Airport.

In several ways, Clearing Yard epitomizes the basic operation of other active hump yards in North America. After inbound trains arrive and are inspected in the receiving yard, cars flow toward the heart of a hump yard: the crest. Here, a lead track or collection of lead tracks gradually climb the incline, peaking at “the hump,” over which railcars are pushed by one or more locomotives, then uncoupled by a switchman or conductor. Once uncoupled, gravity takes the railcars, either individually or in small blocks, into destination tracks in the classification bowl.

As at other hump yards, railcars humped at Clearing are carefully controlled by power switches and retarders, pneumatic devices at the rail level that regulate the speed of humped cars, before entering the assigned destination track. As required, yard crews gather up cuts of cars from the classification yard and forward them to the departure yard, where outbound trains originate.

On the surface, the operation of a hump yard seems simple enough: Trains arrive, get humped into classification tracks, and soon become new trains to faraway destinations. And that basic understanding is enough to satisfy a casual observer. But to the Belt’s six owners (Union Pacific, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, BNSF Railway, Norfolk Southern, and CSX Transportation), whose networks effectively begin or end at Clearing Yard, nothing’s casual about this operation.

The 21st-century Beast

Forced to do more with less by way of procedures rather than property expansions, most current-day efforts to improve yard operation have come by way of automation and information technology.

Recent improvements to the physical plant include the addition of powered switches at the west end of Clearing’s East Receiving Yard. “Prior to powering those switches,” says Assistant Superintendent-Transportation Chris Gorski, “to shove a train up to the crest of the hump was basically a three-part shove.” Now, it’s only a two-part process, and when one train is finished, the next should be in the position to be humped.

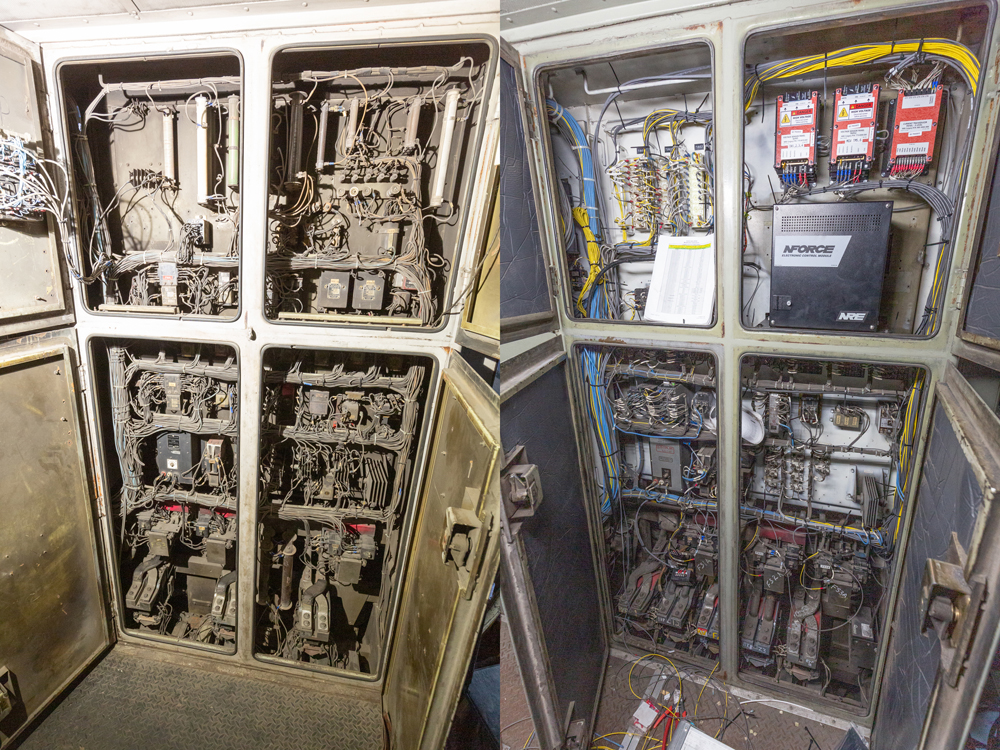

Technologically, the Trainyard Tech Classmaster yard-automation system, introduced in 2009, has been one of the most useful improvements. The system automates many basic classification functions, including the operation of the switches and retarders leading into the bowl tracks. While such an application isn’t completely new to the railroad industry, nor BRC — Trainyard Tech’s product is the third example of yard automation used here — the system’s abilities to deliver key statistics and measure the operation’s performance are clearly advanced.

The Classmaster system integrates diverse devices (such as the remote-controlled hump locomotives, automatic equipment identification gear, car scales at the hump crest, the switches, retarders, radar sensors, and even an anemometer for measuring wind speed, to name a few) to account for the endless number of variables involved in dropping a railcar off the crest. The system uses data from these devices, as well as information on the inherent rolling resistance created by the track structure, to determine the optimum speed at which a railcar should enter, traverse, and exit the retarders. Achieving the optimum speed translates to achieving a perfect balance: The railcar must move quickly enough to clear for the next car coming off the crest, but not so fast so as to damage its freight.

By precisely controlling the flow off the crest, the Trainyard Tech system has reduced the number of “misroutes,” a bugaboo intrinsic in every hump yard. Misroutes, named for those occasions when humped railcars roll onto the wrong track, occur for any number of reasons. In one case, a heavy, loaded railcar rolling quickly off the crest might catch up to a lighter, empty railcar and “tailgate” onto the wrong track. Also, as Gorski explains, misroutes in Clearing occur simply because of short leads in the yard built in a time when railcars were significantly shorter.

The infrastructure running this and other systems has also evolved. In 2013, the railroad brought in Nick Chodorow, now chief information officer; he has overseen upgrades, among them replacing an on-site data center with a hosted provider. That change has provided 24/7 system care, “whereas before, it had to break first,” Chodorow says. “That’s been really helpful for us.

Some upgrades are simply a matter of keeping the railroad’s technology up to date, an ongoing task. “It’s continuing to drive that overarching technology and modernize it,” Chodorow says, “so we can give people better data to make better decisions in real time. And then we can use that as a way to really push.”

The railroad also used computer modeling to produce sophisticated yard simulations that analyze and refine current operations.

BRC managers say that those simulations will help analyze operations at the engine level, analyze costs, and objectively order capital improvements, which prove invaluable to hump yards like Clearing.

— Trains editor David Lassen based this 2016 report on a November 2012 TRAINS magazine story by Sayre C. Kos, who did not participate in the update. Lassen thanks Patrick O’Brien, Tim Coffey, Chris Gorski, and Nick Chodorow at Belt Railway of Chicago for their assistance. Abridged from an article in the out-of-print Trains special issue “Chicago: America’s Rail Capital,” published in 2017.

How do the retarders actually work?

Any 2021 update available for this yard? Has PSR invaded its operations? Many hump yards have been converted to flat switching. How about this one?

Hopefully, the ongoing improvements to rail interchange trackage in the Chicago area have speeded car arrivals and deliveries to the other roads involved. True?

Boy, to model this operation adequately, you would need to buy a retired munti-court tennis building.