BNSF Railway is taking back Montana Rail Link’s lease on the former Northern Pacific main line across Montana and Idaho for one simple reason: To control its own destiny.

In recent years the growth-minded BNSF has made significant capacity investments on its routes to and from the Pacific Northwest.

To the east of MRL, BNSF built new and extended sidings between Fargo, N.D., and the Billings, Mont., area while adding centralized traffic control and positive train control even though it was not mandated to do so. BNSF also expanded its terminals in Forsyth and Glendive, Mont., and Mandan, N.D.

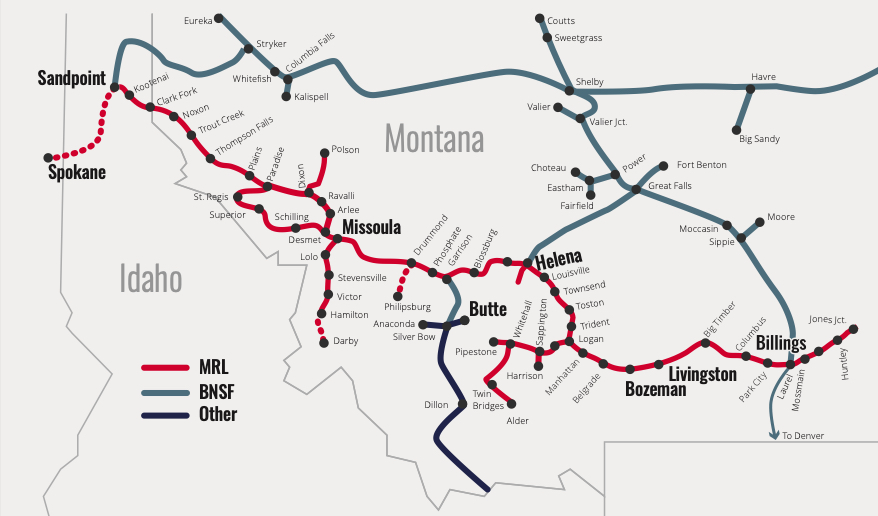

To the west of MRL, BNSF is building a second bridge over Lake Pend Oreille in Sandpoint, Idaho, to eliminate the single-track bottleneck at “The Funnel” where MRL and the Northern Transcon converge. BNSF also has double-tracked from Sandpoint to Spokane, Wash., and installed double track and extended sidings from Spokane to Pasco, Wash.

BNSF can’t add more capacity on the former Great Northern Hi Line across Montana’s northern tier. There’s just no room to double track the Northern Transcon in the confines of the Kootenai River Canyon.

Which brings us to MRL. The unicorn regional railroad was created as a 590-mile bridge route between Burlington Northern at Sandpoint and Jones Junction, near Billings. While MRL has added capacity since its inception in 1987, it has not done so at the same pace as BNSF. The result? BNSF could more than double the traffic carried on its route from Fargo to Jones Junction – if not for Jones Junction-Sandpoint capacity constraints on MRL.

There aren’t physical barriers to adding capacity on Montana Rail Link. But because of the way the 60-year lease is structured – with volume guarantees for MRL – the proudly independent regional has little incentive to lay new track or hire more train crews to support BNSF volume growth and seasonal traffic surges.

Twenty five years ago BNSF CEO Rob Krebs sought to undo the lease. But savvy MRL owner The Washington Companies knew a good deal when it saw one and would not budge. Since then BNSF has taken a carrot-and-stick approach. At times it offered MRL more volume in exchange for capacity expansion projects. At other times BNSF diverted traffic off MRL to the Hi Line. But neither approach, or good faith efforts, could get BNSF and MRL on the same page.

Before the pandemic hit, a traffic surge tapped out capacity on the Hi Line. MRL couldn’t serve as a relief valve because it didn’t have enough crews or sidings. Traffic backed up on BNSF, with congestion raising costs and taking a toll on service. The bottom line? BNSF can’t take full advantage of the millions spent on capacity projects unless the MRL constraint is removed.

So BNSF CEO Katie Farmer did what her predecessors could not: Bought out the MRL lease long before it was set to expire in 2047. Assuming federal regulators approve the transfer, BNSF will be back in full control of the former Northern Pacific main line.

This will give BNSF the ability to add capacity at will. Ultimately, BNSF will gain more operational flexibility and be able to send more trains over what’s now the MRL.

One of the first things BNSF might do is reopen the long-dormant route over Homestake Pass to set up directional running. Westbound traffic would tackle Mullan Pass via Helena, while eastbound empty grain and coal trains would use Homestake Pass via Butte. This would go a long way to create capacity.

Many at BNSF came to view Burlington Northern’s decision to spin off the NP to Montana Rail Link as a costly and shortsighted blunder.

But Darius Gaskins, who was BN’s CEO at the time, insists the MRL deal was necessary. BN didn’t need two parallel mains across Big Sky country, he explains, and due to high labor costs and union-management animosity the decision was made to favor the GN route and lease the NP to Montana Rail Link. “It scratched a bunch of itches. It was a very successful deal,” Gaskins says. “It accomplished what we hoped it would accomplish.”

It does make sense to unwind the MRL lease now, Gaskins says. For one thing, BNSF’s labor costs are likely on par with MRL’s. For another, having full control of the NP and GN will provide BNSF with resilience in the event of a bridge or tunnel calamity. “It gives you a lot of reassurance,” he says.

So shed no tears for Montana Rail Link. It served its purpose, outlived its usefulness as an independent railroad, and will be fondly remembered.

You can reach Bill Stephens at bybillstephens@gmail.com and follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter @bybillstephens

I heard that a Bridge issues arose in the Northwest

BNSF might want to let MRL run a little longer until the sort out their impending strike.

Maybe this serves as a model to preserve rail lines rather than scrapping. I still wonder why the B&O from Cincinnati to St. Louis was allowed to deteriorate to near abandonment and not serve as a Chicago bypass. Blessings.

ANDREW — Add that line to my own list of about three or four days ago on failed Chicago bypasses. These included the Kankakee Belt, Santa Fe’s short-lived ownership of TP&W, and the woebegone Michigan Central line from Porter (Indiana) to Joliet. All of those routes were deteriorated but all of them could have been improved rather than dumped.

Then the railroads moan about Chicago congestion – which for now is CPKC’s route from Toronto and Detroit to KCMO and Houston. Adding more trains to the gridlock.

The former B&O from Cincy to St Louis was allowed to deteriorate because post the Conrail split, CSX directed this traffic via Avon (Indianapolis). There are 2 tunnels between Seymour & Mitchell Indiana which don’t allow double stacks due to clearance, so it could only take merchandise freights and auto racks.

Second issue was in the post C&O/B&O world, they ripped out much of the B&O route between Cincy and Washington DC in West Virginia, leaving the C&O route only. This caused the river level route east access to Queensgate to be pulled up and sold to the Cincy Sports Authority for building stadiums.

This took away all ability for CSX to have have a direct route from the Atlantic seaports to transfer at St Louis without having to navigate Queensgate. It is possible to reconnect the C&O route to the B&O route south of Queensgate.

The “last hope” for the Cincy-St Louis route is perishables. Before the failure of Railex, they had plans to route California produce to Jacksonville via Vincennes Indiana and bring pineapples back west in return. But the long lasting California drought killed this and UP ended up forcing the reefer exchange to Chicago which added time and miles to the service and made it uneconomic.

So while CSX uses Cincy to Seymour as a sort of directional running to Louisville, and CSX provides a weekly as far west as Flora Illinois, the rails are still cut back in O’Fallon (East St Louis). UP would like to use this as a reliever route to reach the former CE&I in Salem.

As soon as the MacArthur bridge rehabilitation work is complete in St Louis, UP is expected to start bringing more traffic to CSX, but in the interim CSX is routing everything through Avon due to the reduced volumes.

CSX has turned all the auto crossing signals from O’Fallon to west of Flora, but the block signals are all still active. The diamond with BNSF at Shattuc has been removed, but are still there with UP.

Bill said, “So shed no tears for Montana Rail Link. It served its purpose, outlived its usefulness as an independent railroad, and will be fondly remembered.”

While I had the honor of working with many fine railroaders at Montana Rail Link, let’s also remember the hundreds of railroaders and their families who had their lives upended by the creation of MRL in 1987. Remember: Not all crafts would be utilized on MRL (such as trainmen/UTU, only engineers). Of those who couldn’t or chose not to work for MRL and wanted to continue with BN were forced to displace junior workers elsewhere, further disrupting lives. For those wondering “Why Now?” with regard to BNSF taking the MRL back after 35 years, I think one component is the passage of time. The vast majority of railroaders affected by the 1987 MRL lease/sale are either retired, deceased, or work elsewhere. Clearly, this transition will be much much less traumatic.

Bill’s analysis gives a good overview of Montana Rail Link, and of course includes something for the railfans: Mentioning Homestake Pass is always a crowd-pleaser, especially amongst those who long for freight trains over Tennessee and Raton Passes. But a bit of elaboration/reality check is order.

And let’s start with the Homestake Pass statement. For those unfamiliar, this is the 122-mile alternate route (to the current route via Helena) between Logan and Garrison via Butte. The line is out of service for 20 miles from Spire Rock to Butte, and hasn’t seen a train in over 40 years. MRL operates the east end of the line from Logan to Pipestone, largely to serve a ballast pit; BNSF operates the west end of the line from Butte to Garrison. The one-time ABS system is gone. Even when owned by Northern Pacific and Burlington Northern, this was never a regular through route for freight trains, and siding capacity was minimal (with most of them removed now). The grade on each side of Homestake Pass is 2.2%, and the east approach from Pipestone to Homestake has a degree of serpentinity that would be almost unmatched in standard-gauge U.S. railroading with many 10- and 12-degree curves. (Take a look on Google Earth if you want to be amazed. The railroad is 5.5 miles further between Butte and Whitehall than the 26.6 miles via Interstate 90.) Basically, the entire railroad would need a redo, depending on the traffic control system put in place, and would be very expensive to maintain. And since the current main line trains change crews at Helena between Missoula and Laurel, this alternate route would set up an awkward crew management situation for a one-way eastward operation and a new crew change point. The line would be worthless for anything but empties trains. While Mullan Pass west of Helena is also a 2.2% grade for westward trains, it is only 1.4% for eastward trains, which would keep trains of any tonnage at all on that route, unless an additional helper situation was created – pretty much the last thing BNSF would want. A truly big-ticket item for a limited number of trains.

And yes, MRL operates two routes between DeSmet (Missoula) and Paradise with the eastward empties trains plying the steeper Evaro Hill line, but the 2.2% hills on the Evaro route are much shorter with much less curvature. Plus, the total mileage of this alternate route is only 64, about half that of the Homestake Pass line.

A lot of the premise of Bill’s analysis is predicated on this misinformation: “BNSF can’t add more capacity on the former Great Northern Hi Line across Montana’s northern tier. There’s just no room to double track the Northern Transcon in the confines of the Kootenai River Canyon.” This statement ranges from not true to needs context.

First of all, a lot of things are possible with enough money, and Berkshire Hathaway has that. (Example: Billions and Billions spent to accommodate traffic during the Bakken Boom.) Also, the $100 million or more that it might take to get a Homestake Pass in service would go a long way into changing the “can’t” to a “could.” And, evidently even Rob Krebs thinks it’s a “could.” In 1998, BNSF added a new siding at Katka, in the heart of the Kootenai River Canyon, which even involved a tunnel. On the west end of the canyon, 7 miles of two main track CTC (with an intermediate crossover) was completed from Bonners Ferry to Crossport. East of the canyon, are long sidings at Yakt and Troy. The supposed bottleneck is 19 miles of 30 MPH (35 MPH for passenger) track between Crossport and Yakt. In these 19 miles are the controlled sidings of Katka and Leonia, which comprise a total of about 3.2 miles of second track. With the two sidings, the furthest a train has to go before reaching a meet/pass location is 6 miles from Crossport to Katka with the Katka-Leonia and Leonia-Yakt segments about 5 miles. And keep in mind, this is river grade, so maintaining track speed (and even most of the turnouts allow it) is not a big deal. As a BN dispatcher who worked the district from Sandpoint to Whitefish and retired before the upgrades in the late 1990s said, “If I’d had had that double track west of Crossport and a long siding at Katka, that job would have been a cake walk.” And since I also worked that area as a dispatcher and other duties, I agree.

And, it should be noted that there are hundreds of locations nationwide with over 5 or 6 miles between sidings or second main tracks on steep grades, unlike the water-level route between Crossport and Yakt. The ability for all trains to maintain track speed in the Kootenai River Canyon is huge contributing factor to this route’s ability to handle more traffic with the additional applied infrastructure.

The second main track west of Crossport is important because the key to fluidity and prioritization on a segment of track with a lower maximum speed is the ability to stage trains as necessary to allow higher-priority trains to meet at the optimum location. In other words, that lower-priority trains are not occupying vital sidings, such as, in this case, Leonia (because there is track capacity to put them elsewhere).

Other things that happened during the early Krebs era (Krebs was quoted at a BNSF Town Hall meeting in Havre, Montana as stating MRL “was the worst mistake BN ever made”) were adding or lengthening four sidings between Great Falls and Laurel, adding numerous trackside warning devices between Shelby and Laurel, expanding staging tracks in the yard at Shelby to accommodate trains to/from the route via Great Falls, and adding 25 miles of second main track between Gildford and Joplin west of Havre. And though the track has yet to be laid, grading for a second main track is in place on the east approach to Flathead Tunnel from Brimstone to Twin Meadows and the east approach to the Kootenai River Canyon from Troy to Yakt, which would have completed a 7-mile section of 2 MT CTC on that side of the canyon, too. Clearly, there was a consensus at BNSF that this route could indeed accommodate more traffic than was currently being operated. As I understand it, the goal was to operate only the amount of traffic required by quota on the MRL with the remainder on an all-BNSF route. But traffic levels dropped shortly after the initial upgrades were done, and others were deemed superfluous at the time.

And lest anyone mention Flathead Tunnel as a similar “can’t be done” limitation: Not the case. The tunnel can handle 55 trains daily or so (demonstrated day after day during the MRL Mullan tunnel collapse in the summer of 2009), and another bore and/or cut is already a consideration. While it would seem to be a huge expenditure (the cost of Flathead Tunnel in today’s dollars would be about $410 million), it’s understandable when one looks at the billions BNSF spent on infrastructure during the Bakken Oil Boom.

In other words, Bill’s claim “a traffic surge tapped out capacity on the Hi Line. MRL couldn’t serve as a relief valve because it didn’t have enough crews or sidings. Traffic backed up on BNSF, with congestion raising costs and taking a toll on service. The bottom line? BNSF can’t take full advantage of the millions spent on capacity projects unless the MRL constraint is removed” can be viewed from the opposite, and more-logical point of view: If BNSF was not restrained by having to operate certain traffic via MRL, might not have BNSF made improvements to its own routes over the years, but didn’t because with a seemingly (at the time) iron-clad traffic guarantee on the MRL the traffic in question didn’t justify the expense? You can agree or not, but clearly Rob Krebs was willing to give it a shot.

Bill’s statement also suggests that a routing via the Hi-Line versus BNSF-Mandan/MRL is an “either-or” proposition. It isn’t. Westward, for example, between Casselton, ND and Sandpoint, ID, a route via MRL is a bit less than 100 miles longer, requires one more road crew, and as many as two helper crews, unnecessary on the Hi-Line route (westward). The steeper grades occur sooner on the Mandan route (first 1 percent grade is 27 miles west of Casselton) than on the Hi-Line route (625 miles west of Casselton); A standard 110-car grain train uses about 2,250 gallons more fuel on the Mandan/MRL routing. And the Mandan/MRL routing can be 12-24 hours slower for general merchandise and unit trains during normal operations, and with it the accompanying longer cycle times for locomotives and rolling stock. Between Laurel and Sandpoint, the all-BNSF routing via Great Falls and Whitefish is less expensive than via MRL for westward unit trains. Though further, not needing helper power or helper crews necessary on the MRL route is a huge savings. For years, BN/BNSF maintained two 2-unit helper consists at Essex to help eastward trains over Marias Pass while MRL maintained a fleet of 18-20 units for traffic over Bozeman and Mullan Passes. (For a more complete synopsis, see: http://www.gngoat.org/GN-MILW-NP.pdf ) In other words, as long as the higher-cost route is used, efficiency is not what it could be. And the longer the higher-cost route is expected to be used, the more incentive to ameliorate those costs with investing in the lower-cost route. It would be one thing if the MRL routing was faster or flatter or shorter, but it’s none of those things.

Another wild card for the future are BNSF’s coal routes which tie-in more to the MRL than BNSF’s Hi-Line. As coal traffic is expected to decline in the coming decades, might BNSF elect to use these routes simply because of available capacity despite their higher operating costs? These are likely to become, as ex-BNSF Executive Chairman Matt Rose called them, “Stranded Assets.”

I’m not suggesting a major shift in traffic one way or the other once BNSF assumes control of what is now the MRL, but it is relatively pointless to use past practice to make a prediction. Thirty-Five years of guaranteed traffic via MRL has skewed the logical progression of the why of how freight is routed across the BN-BNSF Northern Corridor. Immediately prior to MRL in 1987, BN was in the mood to downsize. And then prior to that – all the way back to 1970 – the railroad was preoccupied with merger-related infrastructure modifications and then obtaining capital to fund upgrading and/or building thousands of miles of track for the Powder River Basin coal boom. For the past 52 years, it’s never really been a status-quo operation in the classic sense. We’ll see if that changes.

Thanks for all the great information.

Is the Kootenai River the problem or was it the Flathead Tunnel (which must be an impediment anyway like Stevens Pass Tunnel)?

Is BNSF looking at MRL for traffic growth from the Pacific Northwest through Denver to Texas? What about growth through Lincoln, NE to points beyond east and south?

I wonder why the lease didn’t start at Billings going west instead of Jones Jct? Just seems to make more sense from BNSF perspective or by the lines on the map would suggest. However, Mr. Washington made himself a good deal so assume their was a good reason for picking Jones Jct.

Maybe BNSF will reopen the Darby sub….Darby Mt is where they film Yellowstone….and you can actually stay at the lodge where John Dutton supposedly lives (in the show). Imagine a BNSF tourist train to Darby. I want to go.

Anybody know if the gas local is still running? If so is is lucrative enough for BNSF to keep?

Gas local is still running. I’m sure BNSF will continue to run it.

Great insight by Bill. Makes a lot of sense. I understand Gaskins reasoning, but the one thing I think BN flubbed on with the MRL lease was guaranteeing a minimum amount of traffic to move over MRL lines. I’m sure at the time it seemed like no big thing, but Dennis Washington isn’t a rich man for no reason. Traffic increases or traffic downturns, it didn’t matter, MRL could just sit back and collect cash, trains running or not – literally a license to print money. That’s where Gaskins blundered, and I believe the reason many at BN and BNSF feel the deal was a bad one. And it is going to cost BNSF dearly – I’d love to see the size of the check BNSF is writing Washington to get out of the lease – rest assured it has a lot of zeros!

The size of the check needed was why Krebs wasn’t able to do the deal.

Hmm…did this article say maybe “opening the long dormant Homestake Pass”…??? Whoa, rhetoric, or reality….it would take a lot of money to do it, but then again, there was a time that the idea of re-opening Stampede Pass was considered a no deal. Who knows?

I followed Homestake Pass on Google Earth not long ago. Or at least what I believe to be the line in question. It didn’t strike me as crazily expensive if I indeed looked at the right place. Route was intact, no encroachment, not a lot of grade crossings, three or so intact bridges that may be able to be refurbished, and just one small housing development looked to have popped up adjacent to the right of way (So hopefully not a lot of NIMBY opposition if it were to happen).

I should add that I’m specifically talking about the relatively short out of service portion that looked to be 15-25 miles long or thereabouts. A lot of the pass is in active use today, although obviously a lot of upgrading would be needed for those portions as well to get them in shape for heavy mainline use.

I doubt it actually happens, but at least where the inactive segment of Homestake Pass is concerned, I didn’t see anything that appeared to be a major deterrent to restoring it for service. The big question in my mind isn’t the cost to bring this route into service, but the expense to operate it. Heavy grades and lots of curves makes for an expensive operation.

Hopefully the demand for capacity ends up justifying that, but I’ll believe it when I see it.

Agree with Jacob, nice write up and gave some good insight on why BNSF would be making the move now. It would be interesting to know what Amtrak thinks as I believe Big Sky rail commission is trying to reinstate passenger rail over the line as well. BNSF might put argument that taking control & adding capacity is a good thing if Amtrak service is expanded in the mix as well

…

I can see STB misguided idea on what dictates competition by putting up hurdles. Especially if MRL comes up with a proposed plan of capacity improvements even though a piece a paper saying your going to do something doesn’t mean you are going to do something as most of us probably know about life. I would proceed that way if I owned MRL in order to keep a good thing going for my pocketbook another 3 or so years. Especially with the current admin blaming big railroads for inflation and ignoring the fact that big part of increased shipping /container prices has a lot to do with shipping & logistic companies owning and parking those big container ships off Port of LA/Long Beach having record revenues & profits.

You’re right about not being to add a second main thru the Kootenai River Canyon on the former GN. However, BNSF could add a second main between Williston, ND to Shelby, MT.

On MRL, the NP had a double track main line from Garrison to Missoula, MT until 1959 when CTC was installed. To put the second main back in, 3 tunnels would need to be enlarged but it would be doable.

Thank you Bill for the background. I learned a lot.