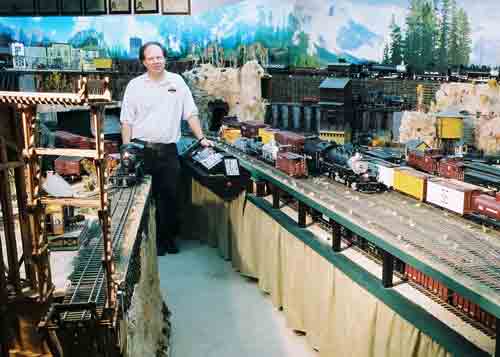

The scale of the bridge is a good introduction to Barry’s large-scale indoor layout. As the visitor soon discovers, the entire upstairs of Barry’s house has been converted into a “train floor.” A large room, hallway, and small room-about 1,000 square feet altogether-are filled with track and scenery. Barry’s Colorado & Western depicts the narrow-gauge railroads of Colorado in the fall of 1952.

Barry explains how it all started: “In 1969 I went to visit Colorado. I was fascinated by Colorado trains. The scenery was absolutely mindblowing to me, because I always lived in flat Houston, Texas.” After a childhood with HO trains, hot rods replaced model railroads as Barry’s favorite hobby. Then he got married and, one day, his wife asked him to go with her to the craft shop to look at cross-stitch patterns. There, Barry saw his first LGB catalog. That was in 1985 and the rest, as they say, is history. He bought a starter set and was hooked: “I saw how big it was and how well it ran.”

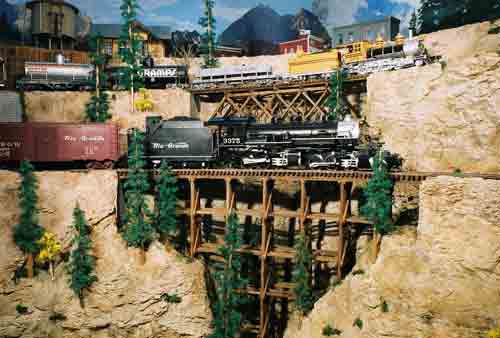

Barry’s trains have come a long way from that starter set. Wandering through a doorway, the visitor discovers a small town, Silverton, perched high in the mountains. Trestles cross ravines and bridges span doorways, all in front of a photo backdrop of Colorado’s mountains covered with yellow aspens and dark-green conifers, with the blue sky above. As in a child’s dream, the railroad’s tunnels go through walls and closets before reaching the main yard in Durango. More towns are nestled in the mountains above and across the valley below, surrounded by the sparse trees, shrubs, and grasses that characterize the vegetation of the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

There is a lot of track here-about 1,200 feet. However, even though the length of track resembles that of many large garden railroads, the Colorado & Western does not appear crowded. “My goal has been to depict the massiveness of Colorado-the little trains traveling through big scenery.” Barry’s layout captures this impression through its clever use of the three-dimensional space. Instead of running next to each other, the C&W’s tracks are scattered over the steep mountainsides of Barry’s layout. Each track goes somewhere and every place is reached only by one set of tracks. (In fact, there are connecting tracks that allow continuous running on several loops during open houses, but the railroad is usually operated as a point-to-point line.)

With this sense of purpose and so much vertical space between the tracks, Barry’s layout conveys the impression of lonely trains battling steep grades in the mountains. Barry explains: “What got me started doing something with floor-to-ceiling scenery was reading the book, Model Railroading with John Allen. I kept thinking, if John could do it in HO, there is no reason why I couldn’t do it in 1:22.5-scale. Another inspiration has been Malcolm Furlow. His vertical use of scenery has given me the inspiration to do things that I probably would not have done before.”

Locomotives on the Colorado & Western have to work hard, just like they did on the prototype Denver & Rio Grande Western. Grades of up to 3% challenge the motive power, and trains are usually short.

Barry models to a scale of 1:22.5, rather than the more common 1:20.3. The reason is simple: When Barry started large-scale modeling in 1985, the only available equipment was LGB’s 1:22.5-scale line. He bought some cars and scratchbuilt those he could not buy. “Back then, there wasn’t much 1950s Colorado equipment available off the shelf,” Barry explains. His first project was two, frameless Gramps tank cars, which still run on his layout today. Faced with a lack of suitable locomotives, Barry built a 2-8-0

C-16. A K-27 followed and, since then, a steady stream of scratchbuilt rolling stock has come from his workbench. Over the last 19 years, he has built about 30 locomotives and countless cars.

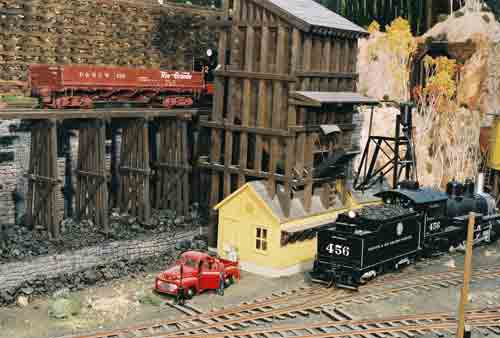

Today, a few of his original LGB cars remain, but most rolling stock is scratchbuilt to Barry’s high standards. Because he usually needs multiples of everything, he takes molds from his scratchbuilt parts and replicates them by casting. Barry’s philosophy sounds simple: “If I can purchase it, then I will do that and put a kit together. If I can’t, I will scratchbuild it.” In practice, however, this means that almost everything on his layout is scratchbuilt, with the exception of the above-mentioned LGB cars and a few water towers from Piko and Pola. Barry built most of his buildings, including the impressive roundhouse in Durango, as well as the coaling tower, mine, oil racks, and other lineside industries. Some models, such as the stock pens, were built by Barry’s friends.

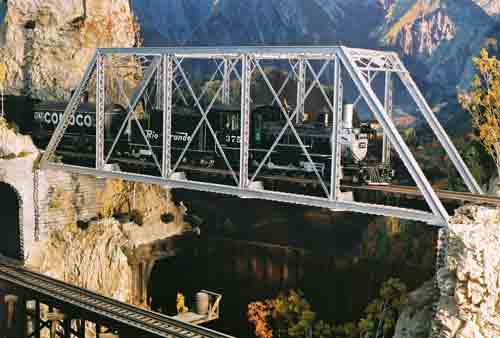

Barry is especially proud of his bridges: “I love bridges. Bridges take you from one section of the layout to another. A bridge is a transition as well as a way of getting tracks over another line. The Lobato Bridge is probably the model of which I am most proud. I went to the real bridge in Chama, New Mexico, crawled around with a tape measure, measured the thing completely, then built it to scale.” Trains cross 17 feet above the foyer below on this 14-foot-long bridge. The individual bents are up to four feet high, and even the biggest locomotives of the D&RGW, the K-36 and K-37, look small on this immense structure.

This is Barry’s second Colorado & Western. He started working on the current layout after his family moved to this house in 1997. “When we were looking at houses, the train layout was a major consideration,” admits Barry. He began working on this layout in February 1999, after moving a few walls and closets. With the experience of the previous layout, he made sure his new layout had the clearances he needed to run large locomotives. He recommends that beginners plan their layouts carefully, then execute their plans. “Make minor adjustments, but stay on track so you are not wasting or losing time.” For example, Barry’s layout from the beginning included a loop of standard-gauge track at the “valley” level, even though he didn’t have any standard-gauge equipment then.

Because Barry handlaid all his track with code-250 rail, using ties cut on a table saw and track nails for HO-gauge track, it was easy to incorporate three rail, dual-gauge track at this stage. His switches are handmade, using Llagas Creek components and his own castings for the more complex dual-gauge switches. The handlaid track makes the railroad blend nicely with the scenery; its curves flow naturally.

Minimum radius on the narrow-gauge tracks is four feet. The smallest radius of the dual-gauge track measures five feet. In the tight confines of the indoor space, many switches are located on curves. Inventive track configurations, such as a “gantlet” track, where two tracks are overlaid, rather than being built next to each other, help keep operations interesting.

As a result of all this careful planning, even the huge standard-gauge Denver & Salt Lake 2-6-6-0 Mallet required only one minor “adjustment” to the size of a single tunnel portal built years ago. Standing next to this behemoth, the narrow-gauge equipment looks diminutive, even though the D&RGW’s K-36 and K-37 locomotives are among the largest narrow-gauge locomotives in the world.

For most of his locomotive scratchbuilding projects, Barry uses wheels and gearboxes from LGB. He explains: “It’s the best. LGB’s gearboxes are reliable and run well. LGB’s flanges work extremely well-they stay on the track. They may be a bit oversize, but that never has been a major consideration of mine. To me, it has to run well first and look good second.”

Barry’s finely detailed, scratchbuilt trains are not display models, but are designed to operate. Once a week, the Colorado & Western truly comes to life, when a number of friends gather to operate trains. Using RailOp software, freight trains are made up and, with much switching, cars are picked up and dropped off at various points along the way. Barry uses Kadee couplers with remotely controlled magnets to allow switching on tracks that are hard to reach. Underneath the railroad is a large storage yard. Like many scratchbuilders, Barry has accumulated more rolling stock than his railroad can handle. Even with a railroad as large as this, prototypical operation usually has only four trains running on the mainline at a time. Add to that two yard switchers, and there is enough to keep a few friends busy for an evening, while maintaining the feeling of loneliness so characteristic of the Colorado mountains.

Barry operates his trains with Easy DCC, a digital command-control system. His locomotives are equipped with Digitrax decoders. Barry explains: “The reason I went to DCC is because, with it, I can run any train anywhere, with the capability of blowing a specific whistle or sounding the bell on any particular locomotive.” Every locomotive is equipped with a Phoenix 2K2 sound system. Barry especially likes the “real time” whistles, which sound as long as you hold the button.

The lonely whistle of a K-27 locomotive echoes in the mountains, as the short train passes the stock pens at Lobato. The caboose vanishes around a rock outcrop and all is quiet again. You can almost hear the wind rustling the grass growing next to the tracks.

Barry has liked trains since his parents gave him a plastic pull train at the age of two years old. He says it was one of the best gifts he ever got, as it set him on his journey as a model railroader, going on to HO and Lionel trains in his youth. After graduating from high school, college, jobs, cars, and girls took most of his time. He married Janet in 1985. After discovering large scale, it became his quest to change people’s idea that it was not just toy trains around the Christmas tree, but a scale model railroad with may fine qualities. During his 20-year journey, he became a Master Model Railroader at the age of 34, the youngest person to achieve it at the time and also the first to do it exclusively in large scale.

Blake, Barry’s favorite (only) son is 12 years old. He became a “Choo-Choo Guy” in 1999, when they started the current layout. To this day, he too enjoys the trains-just not as much as his Dad.

Barry’s job as a field engineer (repairing business machines) has kept him busy for the past 22 years. Janet, a stay-at-home mom, loves to cross-stitch.

The railway at a glance

Name: Colorado & Western

Size of railroad: 1,000 square feet

Scale: 1:22.5

Gauge: 45 & 64 mm (ga. 1 & 3)

Era: Fall of 1952

Theme: Mountain railroading in Colorado on the Denver & Rio Grande

Age: 8 years

Motive power: 32 locomotives, mostly scratchbuilt K-series, narrow-gauge Mikados. Standard-gauge engines include a 2-6-6-0, 2-4-4-2, and an Alco S1

Length of mainline: About 400′

Maximum grade: 3%

Type of track: Hand laid, weathered, code-250 rail; turnouts use cast-urethane frogs with Llagas Creek points and guard rails; 15 dual-gauge and over 35 narrow-gauge turnouts

Minimum radius: 4′ for narrow gauge; 5′ for standard gauge

Structures: Scratchbuilt and kit-built buildings

Control system: Easy DCC with five wireless throttles and three, 10-amp power boosters. All locomotives have Digitrax DG583S decoders with Phoenix 2K2 sound boards

Would be nice to see overview sketch of track plan.

Impressive hand laid track. I found outdoor track is a lot more stable hand laid with staggered rail joints except at switches and crossings. Articles on how he build switches would be fantastic.