Zimo

Available from:

Train Li

3 Kensington Way

Upton MA 01568

Price: $180-$240, depending on configuration

Website: www.trainli.com

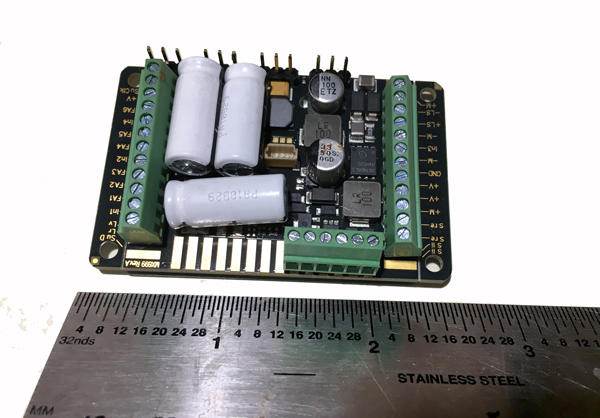

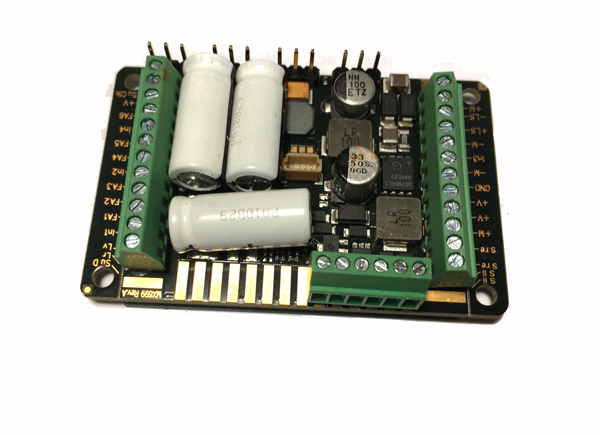

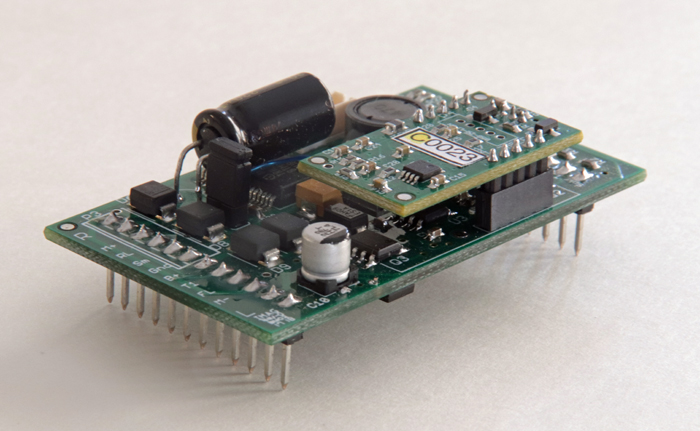

Zimo MX699 motion/sound DCC decoder; light, servo, and smoke control outputs;

multiple configurations available. Dimensions: 2″ x 15/8″ x 5/8 “

Pros: Smooth motor control; high current output; many outputs for lights, servos, pulsed smoke; available in multiple configurations including “Plug-and-play” and full screw terminals; built-in “Keep Alive” keeps sound and power going over dirty track; extensive choice of individual sound files to choose from; high degree of customization for individual locomotives; good customer support when you have questions about setting up various control parameters

Cons: Limited ability to preview sounds before selecting suitable sound file; some sound files have more flexibility than others in choosing options, but no documentation indicating which do and which do not; documentation written for the complete class of decoder, not specific to individual sound files; sound-default settings do not necessarily match common US DCC practice

The decoder comes in a handful of different connection options—some with solder pads, some with screw terminals—and versions designed to plug into the onboard plug-and-play sockets from Bachmann, Aristo-Craft, and others. All are the same basic board, but with slightly different components for interfacing with the wiring in the locomotive. The board has a total current capacity of 6 amps and can handle peak loads of up to 10 amps. There are 15 function outputs (lights, smoke), each rated at 1 amp, but the whole group is limited to 2 amps total. The board also has four servo outputs.

The board arrives packed in a small tin, held in place by high-density foam. The tin has a description of the decoder but, alas, it’s in German, leaving you to refer to the online manual for English hook-up instructions (more on that later). Mine also had the sound file and software version hand-written on the sheet. Knowing what software version you have plays an important part in programming via the manual, as there are some functions that do not apply to older software versions.

When you order this decoder from your Zimo dealer, you have to specify which sound file you want loaded onto it. This is where things get tricky. There’s an extensive library of sounds, recorded from locomotives all across the globe. That’s the good news. The downside is that sound samples for all are not posted on Zimo’s website, so you often have no way of previewing the sounds you may actually want for your locomotive. Some sound files offer a small handful of options for whistles and bells (typically five or six), while others offer no variations. There is no documentation on the website telling you which files offer what so, in many ways, you’re flying blind. The theory seems to be that you would know the locomotive into which you’re installing the decoder (GP-7, 2-6-0, Shay, etc.) and choose the appropriate sound file as they’ve labeled them. I like to audition sounds, especially for locomotive whistles, so the lack of ability to preview the sounds bugged me. Train-Li tells me they’re working with Zimo to increase the number of website samples.

I chose the “Colorado & Southern #9” recording to be loaded on the review sample. It didn’t have a preview sample available but, having produced a series of news stories on the prototype’s return to service, I had plenty of footage as a reference.

Our review sample had screw terminals so, once I downloaded the instruction manual from Zimo’s website, installation was a relatively simple matter of attaching the requisite wires to the correct terminals. I installed this in my Bachmann K-27. This is a battery R/C installation and I’m using an Airwire T-5000 throttle and Tam Valley Depot receiver to provide DCC control to the decoder. In a track-powered DCC environment, you’d hook up the rail inputs to the decoder and use whatever base station you have chosen.

When I applied power, the bell rang for a short time, then stopped. Apparently, that was its way of testing itself to make sure it was working. The user must then actually turn the sounds on by hitting the “8” key on the transmitter. Once I did that, I had control over the sounds. Problem: the sounds are mapped to function keys slightly differently than what is “standard” for US DCC-function mapping. For instance, the “2” key usually gives you a whistle for as long as you hold down that button. In this case, it played the grade crossing “long-long-short-long” whistle. Pressing the “3” key blew the whistle, but you had to press it once to start, then press it again to stop it. You can correct these by re-mapping, but I’d much prefer to have the US-based sound files come already loaded on the decoder to US mapping standards. Also, when starting out, the whistle automatically blows. This would ordinarily be good, except it just blows once instead of the US standard of twice for forward, three times for reverse. There’s no way to change that; the only option is to turn off the automatic whistle sounds (by lowering their volume), then blowing the whistle manually. Train-Li says they will pass this on to Zimo so it can be corrected.

When I bumped the throttle to step one, the locomotive began to creep slowly along with a quiet, barely audible chuff. The Zimo decoder uses the motor’s back EMF (BEMF) to control the sounds—particularly that of how hard the locomotive is working. When the locomotive is just creeping along with no load, the prototype would have little to no audible chuff. Neither does the Zimo board.

A side note: When Train-Li sent the decoder, they recommended downloading the manual and reading it to understand the available functions and how to program the board. Without the board in front of me, it didn’t make a lot of sense. Once I got the board, and began to see what first seemed like quirks in its operation, I went back to the manual and realized these are things that needed to be set up by the user, specific to how the locomotive runs. Make sure that, when you order your decoder, you have your dealer send the documentation for the specific sound file you’re ordering. This will tell you which sounds are available, which functions these sounds are mapped to, and to which specific CV values they are set, which may be different than the defaults listed in the manual. (The manual, while extensive in its coverage, is generic regarding specific sound files.)

Wiring the decoder into the locomotive was only a small part of the full installation. I then set about tweaking the decoder to get the most out of it. Some things were intuitive (like setting the BEMF-controlled chuff rate, master volume, and motor control CVs for

acceleration and deceleration), while others took some figuring out—particularly function-mapping. Zimo has an unusual way of mapping functions that isn’t clear from the instructions. It also requires you to know specifics about your sound file and what is mapped where. This took some getting used to but, once it clicked, it was easy to navigate. I credit the patience of Train-Li in being able to talk me through some of this stuff.

Jumping through all those programming hoops results in a locomotive that runs and sounds great, particularly the chuff and its response to load. If you run the engine light, the chuff is very quiet. Add a few cars, and the chuff increases in volume because the load is slightly more. Run that train up a grade, and the volume of the chuff increases even more. When you back off the throttle, the chuff almost disappears as the locomotive slows to a stop. The BEMF-calibrated chuff remains consistent with the drivers throughout the speed range. The decoder also offers the option of a trigger input for locomotives with optical, magnetic, or mechanical chuff triggers. You can also tie a fan-driven smoke unit to the chuff in order to get pulsed smoke in sync with the drivers. My K-27 lacks a functioning smoke unit, so I could not hook this up. I did connect the locomotive’s classification lights up to one of the lighting-function outputs.

The sounds themselves are good. The whistle isn’t as clear as it sounds in the footage I shot but it’s definitely the same whistle. The chuff is great and other sounds are also well-reproduced. Since each sound file is different, sourced from different sound engineers, I hesitate to spend a lot of time discussing the quality of the sound, since it’s likely to vary.

Motor control is smooth and even, and the BEMF works to keep the locomotive running at the same speed for a given throttle setting regardless of the load. The decoder offers the ability for “prototypical braking,” where you set the deceleration rate to be really long so that, when you decrease the throttle, the locomotive takes a l-o-n-g time to respond. You then use a function key to “apply the brake” to bring the locomotive to a stop. It also offers a momentum-override function for those times when you want precise control of the speed from your handheld throttle. “Shunting speed, reduces the speed of the locomotive to half, usually used for switching operations. My K-27 already has a 2:1 reduction gearhead installed, so it runs plenty slowly already. Still, this is a great feature to have with junior engineers.

The decoder comes equipped with “keep alive” capacitors that allow it to continue running over dirty track, where contact may be momentarily lost. I run battery power so, just to test their capacity, I shut the power off. The locomotive continued running for around five seconds before the motor stopped. Sound continued for a few more seconds before it stopped, and the cab and firebox lights stayed on for a few minutes after power was shut off. For one used to turning off the power and having things shut down, this took a little bit of getting used to.

Overall, I’m impressed with this decoder. Like many latest-generation decoders, it’s complex in what it can do, so programming them is likewise complex. But that’s a week of fiddling for a lifetime of really cool operation once it’s set up. I hope to see Zimo increase the availability of sound samples on their website, so that potential customers can get a better sense of what’s available.