Lillian “Curly” Lawrence and the history of live-steam locomotives

Lillian “Curly” Lawrence was a British model engineer who lived from 1882 to 1967. He built his first live-steam locomotive at the age of 13 on a used treadle lathe. A curious and reclusive fellow, he wrote live-steam columns for British model-engineering magazines under the pen name of “LBSC”–the initials of his favorite line and one-time employer, the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway.

Curly was a prolific model-locomotive designer. Over a 45-year period he produced an astonishing 150 model locomotives, described in serialized construction articles he referred to as his “words and music.” LBSC wrote in simple, understandable terms so that even the most inexperienced of builders could successfully construct a live-steam model locomotive on a home lathe (back when most home workshops had a lathe) and fire it on domestic heating coal.

Not only did he cover building locomotives, he wrote about machining techniques, locomotive operations, and even workshop tools (often with a rather wry, humorous style). His book Shop, Shed and Road, which first appeared in 1929, is still regarded by many as a standard reference for building steam engines. Several editions were published and it is readily available from used-book dealers and online auctions. It’s a worthwhile read for anyone interested in the technical and design aspects of small-scale live steam.

If you have heard of LBSC, it has probably been in the context of larger-scale locomotives. He designed locomotives in many different sizes, from gauge 0 to 5″ gauge and, in fact, of the 150 or so locomotives he designed, 30 were for gauge 0 and gauge 1 track. Curly lived for a couple of years in the US during the 1930s and, influenced by American railway practice, produced designs for a number of North American locomotives as well as British ones. LBSC’s locomotives were largely freelance and not highly detailed. However, his design approach was to scale down full-size-locomotive practice wherever possible. This was particularly true for his gauge-0 and gauge-1 locomotive designs, whose performance was far superior than that of the commercial toy steam engines available in the early part of the twentieth century.

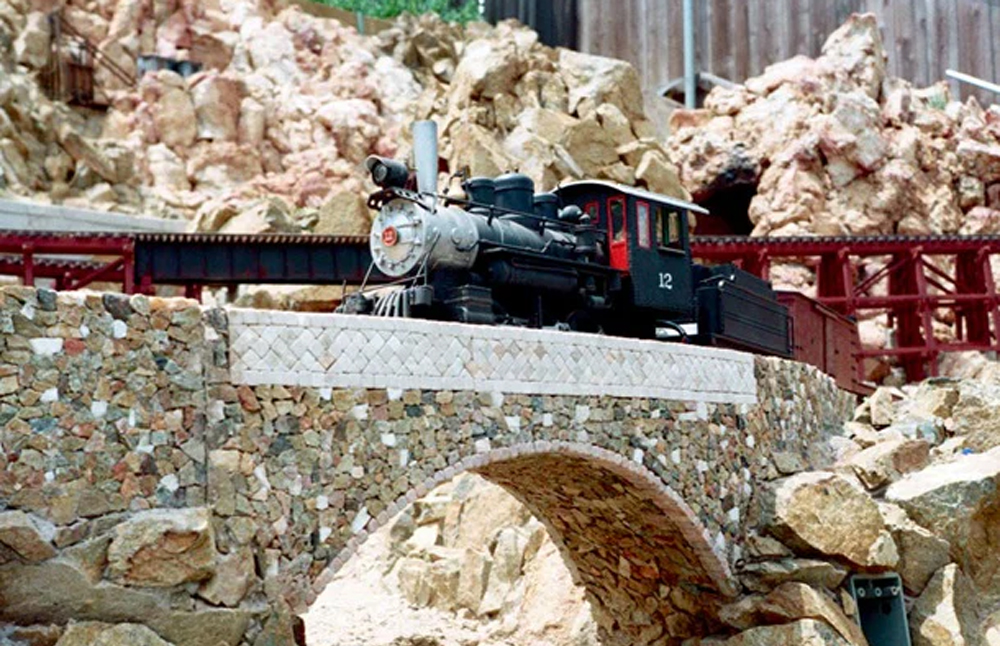

A design produced in the 1930s by LBSC was the basis for Aster’s Southern Railway “Schools” class 4-4-0 in 1975, considered to be the first “modern era,” gauge 1, production, live-steam locomotive. In examining a good number of the most current commercial small-scale steam locomotives, you will find a certain degree of Curly’s influence in their design. In 1926, LBSC designed Sir Morris de Cowley, (a play on the tradition of naming locomotives of British railways and a particular British automobile manufacturer of the day), it was a freelance, coal fired, 0-gauge Pacific that was capable of hauling full-size passengers. Several Sir Morris locomotives have been built over the years and the accompanying photo shows an example (a little modified from LBSC’s design) made by an unknown builder.

During World War II, LBSC produced designs for two locomotives, Bat and Owl, that could be built in either gauge 1 or gauge 0, for alcohol or coal firing. His premise was that these locomotives could be operated indoors during the wartime blackout, since (he claimed) large-scale locomotives operating outdoors in evening would cast unwanted light from their fireboxes! Always ahead of his time, he even produced a couple of narrow-gauge designs for use on gauge 1 track, namely an 0-4-0 industrial locomotive called Small Bass, and Zoe, a massive 2-8-2 tender locomotive, not to mention an 0-gauge diesel shunter with a boiler and single-cylinder steam engine hidden inside.

It is amazing to note that castings and drawings for Bat and Sir Morris de Cowley, along with a large number of LBSC’s larger-scale locomotives, remain available to this day from suppliers in the UK, a testament to the success of his designs. I think LBSC would be pleased.