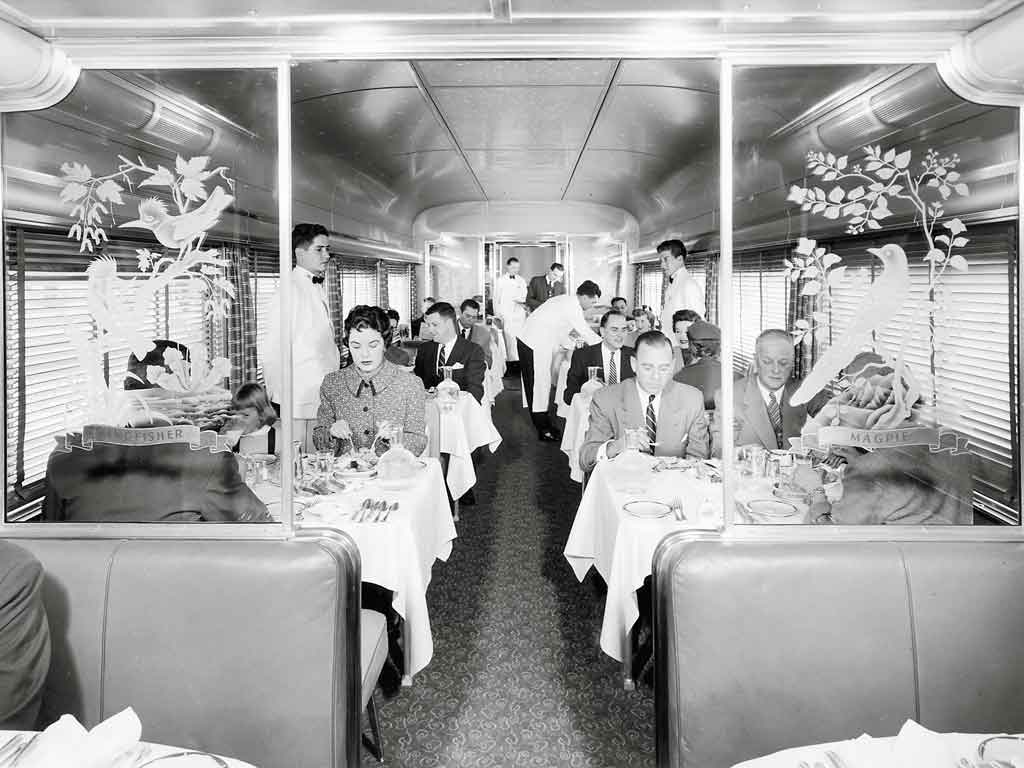

Mind-blowing dining car facts

Dining by rail was transformed from a disgusting experience to a culinary calling card pitting one railroad against another to garner passengers. At the table, passengers enjoyed fine food served with the grace and style of the best restaurants. What we didn’t see was the world and culture of the dining car staff and beyond them the supporting commissary workers. Let us look further with these five mind-blowing dining car facts.

No. 1 Are these your leftovers?

At the beginning of American railroading — the late 1820s — the passenger experience was less than satisfactory, compared to what traveling by train would become. Food aboard a train, let alone a fine meal in the dining car, was not existent. There were no dining cars as we would come to know and love.

Into the 1880s and 1890s, trains in some parts of the U.S. made meal stops at trackside roadhouses to accommodate passenger hunger. Such stops lasted 20 to 30 minutes and where anything but civil affairs or something that came close to fine dining of the time. Trackside roadhouses were characterized by bitter coffee, greasy meats, unsanitary eating facilities and rude service.

In some cases, the train conductor and roadhouse proprietor worked a scam on the unsuspecting passengers. The conductor, for a fee, would have the train’s whistle blown early, shorting the dining period by five or 10 minutes. With poor service, most passengers would have had only enough time for a few bites before stampeding back to the train. The partially eaten food would then be gathered, returned to the kitchen, and held for service to the next train of hungry patrons. Are these your leftovers?

No. 2 Martha Washington’s cool diner

Dining cars did become rolling five-star restaurants, providing remarkable culinary delights presented with impeccable service. Railroads constantly worked to improve service, introduce new recipes, and enhance dining car designs.

What does Martha Washington have to do with railroad dining? There were no trains when she was alive.

Between 1923 and 1930, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had Pullman build a series of dining cars that made up the F-4b Colonial series. The diners were named for famous women of the colonial period, Martha Washington among them. In 1930 a large shed adjacent to the B&O’s Mount Clare Shops in Baltimore was closed off to all but specifically authorized workers. What took place inside was a mystery. It was, however, a cool project, to say the least.

In the shed, Martha Washington was being fitted with the first true air conditioner applied to a railcar. Shopmen from the B&O worked with the technicians of the Carrier Engineering Corp., to install the system. Yes, that is the same Carrier that today supplies home heating and cooling equipment.

The Martha Washington, with its colonial-inspired interior design and comfortably cool atmosphere, was a big hit with B&O passengers.

No. 3 Mr. Green went pearl diving

The dining car staff was a close-knit group who worked together with precision to serve passengers. The staff exhibited intense pride in providing good food with outstanding service. To accomplish this, railroads had strict rules the staff was required to follow. Among these rules were notations on how passengers were to be treated. At times the dining car staff needed to express themselves on various topics or in a manner that was not for public consumption.

To carry on a conversation within the ear of the passenger, but not to run the risk of them understanding what was being said, the dining car staff had a language all their own. If you weren’t part of the crew, you would not understand what was being said.

Example: Mr. Sam had been flattened out all night. It was nothing but 48 flat and standing. For all he worked, however, he hadn’t experienced the lamb’s tongue maybe once or twice that evening. The snakes were really biting. Meanwhile back in the kitchen, Mr. Green was just as busy running between watching television and pearl diving. The entire crew was looking forward to getting greased and a bit of gold-bricking at the end of the run.

Flattened out: a waiter whose deuce (two-person table) and large (four-person table) were filled with customers.

48 flat and standing: a 48-seat dining car that is filled to capacity with additional passengers waiting.

Lamb’s tongue: a generous tip, usually a dollar or more.

Snakes: someone who does not leave a tip.

Mr. Green: the newest man on the crew.

Watching television: doing dishes in a dishwasher with a window in the door.

Pearl diving or pearl diver: washing the dishes, pots, pans, and kitchen utensils by hand, or the fourth cook assigned to do the dishes.

Greased: to get paid.

Gold-bricking: taking some time off.

No. 4 Cantaloupe pie

Yes, this is strange. Railroads like to impress potential shippers. Sometimes, good track, reliable equipment, fast service, and great rates were only a part of the pitch. On occasion, the little extra touches illustrated that a railroad was sincerely interested in gaining a shipper’s business.

One such instance is the case of the Texas & Pacific Railroad and several prominent Pacific Coast fruit growers. Chef Eddie Pierce was assigned to a train the T&P was hosting for this group of fruit growers. T&P was hoping they would be able to transport the growers’ products, one of which was cantaloupe. Pierce developed this recipe for cantaloupe pie, in an effort to impress the growers.

Cantaloupe pie filling:

- 1 large cantaloupe, well ripened

- 1 cup cold water

- 4 Tbsp. cornstarch

- 2 Tbsp. flour

- 1 ½ cups sugar

- 3 Tbsp. butter

- 1/8 tsp. nutmeg

- 1 baked 9-inch pie crust

Preheat oven to 275 degrees. Dissolve cornstarch in cold water and let stand. Cut cantaloupe in half, taking care not to lose juice. Strain juice from seeds of cantaloupe into a medium saucepan, mashing to gain maximum juice, and discard seeds. Remove meat of cantaloupe and put through ricer, or chop in food processor and put in saucepan, conserving both meat and juice. Stir cornstarch/water mixture into saucepan and bring all to a boil over high heat. Reduce heat and continue boiling for 5 minutes. Blend flour and sugar together and add slowly to the hot mixture, stirring constantly. Add butter and nutmeg and stir until thoroughly combined. Refrigerate to cool. Meanwhile, bake a single pie crust and allow to cool. Before cantaloupe mixture sets, pour into crust. Top with meringue.

Meringue:

- 3 egg whites, stiffly beaten

- 1 tsp. sugar

In mixing bowl, beat egg whites until frothy. Continue beating and slowly add sugar. Beat mixture until stiff — peaks form and hold. Cover pie with meringue. Cover pie with meringue. Bake in 400-degree oven until brown, about 10 minutes.

No. 5 Great Big Baked Potatoes

Occasionally it pays to be nosy and eavesdrop on someone’s conversation. Such was the case in December 1908 aboard the Northern Pacific’s North Coast Limited. Hazen J. Titus, newly appointed superintendent of dining cars, tuned his ears into a conversation between two potato farmers. The farmers were lamenting the spuds they had grown but were unable to sell. They feared the potatoes would be nothing more than hog feed. Joining the conversation, Titus discovered that these were no ordinary spuds. These were mega potatoes, if you will, growing to weigh between 1 to 5 pounds each! The farmers related complaints about poor taste, texture, and appearance.

When the farmers detrained at Yakima, Wash., Titus followed and procured a large box of the gigantic potatoes. He continued on his trip westward, ultimately arriving at Northern Pacific’s Seattle commissary. Here, several days were spent experimenting with various cooking methods in an attempt to find the perfect means of preparing the potatoes.

The results: When a 2-pound spud was baked for 2 hours, then gently rolled to loosen the skin, split lengthwise and slathered with butter, well, the outcome was a baked potato that tasted better than any old russet, including those from Idaho. Titus knew he had struck on an item that must be added to Northern Pacific dining car menus.

Titus returned to the main commissary in St. Paul, Minn., late in December 1908. Immediately, he ordered all the big potatoes he could find. He was looking for spuds in the 1-to-2-pound range. On Feb. 9, 1909, aboard the North Coast Limited, the Great Big Baked Potato was offered for the first time. For all of 10 cents passengers could enjoy an outstanding, exceedingly large, perfectly baked potato.

The Great Big Baked Potato became a dining car legend for the Northern Pacific. The railroad even developed an advertising song to help promote the gigantic spuds.

As neither the Burlington nor The Milwaukee Road were noted for their diner cuisine between Chicago-Minneapolis, I thoroughly looked forward to dinner on the “North Coast” and breakfast+lunch on the “Empire Builder.” A tough choice in the summer years of the early 1960s, as both trains offered a terrific prime rib for dinner.

Until Amtrak killed the all-Pullman status of the “Super Chief,” the Santa Fe maintained consistently high food preparation standards (as Amtrak declined to the level of the Pennsy.)

Beyond the 1990s and into the mid 2000 teens, only VIA Rail offered aboard its transcontinental “The Canadian” first class meal preparation, with a different menu for every meal–and such meals! And the dining car manager was most eager to oblige with a perfectly prepared Martini (shaken, not stirred).