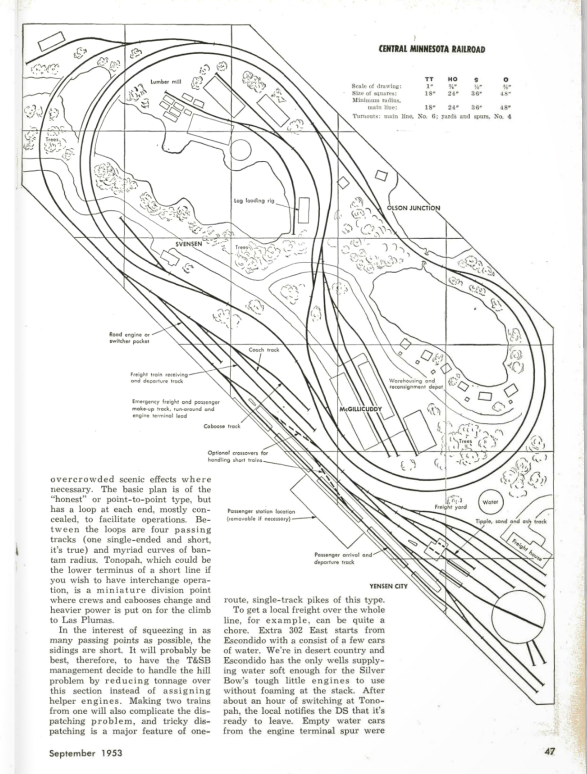

A John Armstrong inspired layout: In March of 1952 Model Railroader magazine began a series called Track Plan of the Month. A frequent contributor was John Armstrong, an undisputed genius of model railroad planning. Armstrong designed two track plans for the September 1953 issue. John rotated the center line of the layouts’ footprints 45-degrees and chose the title, “On the Bias.”

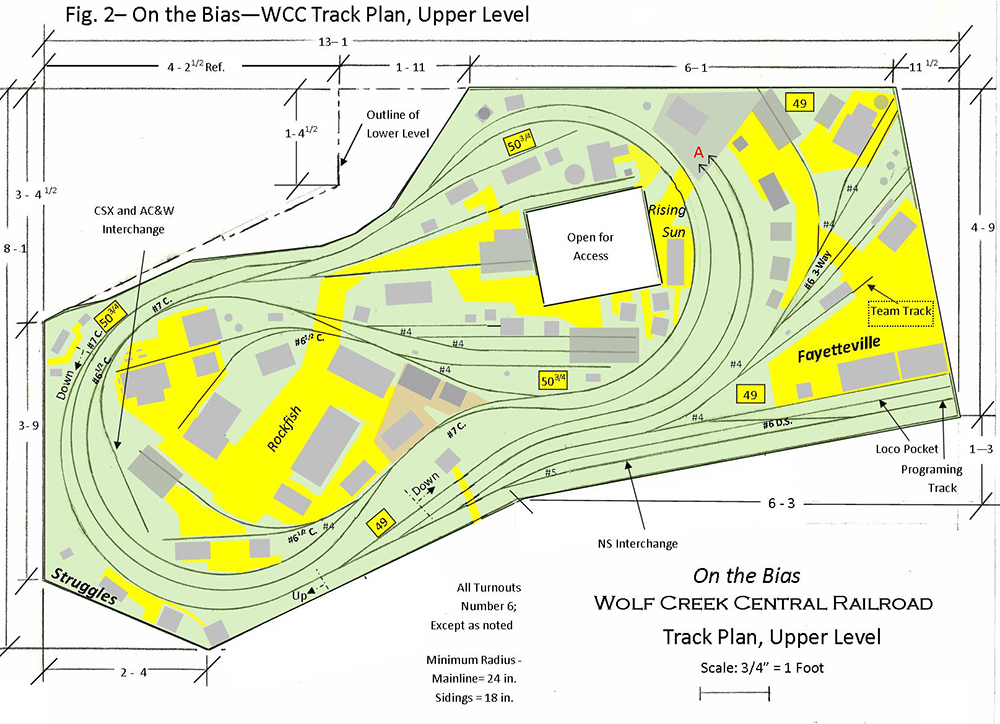

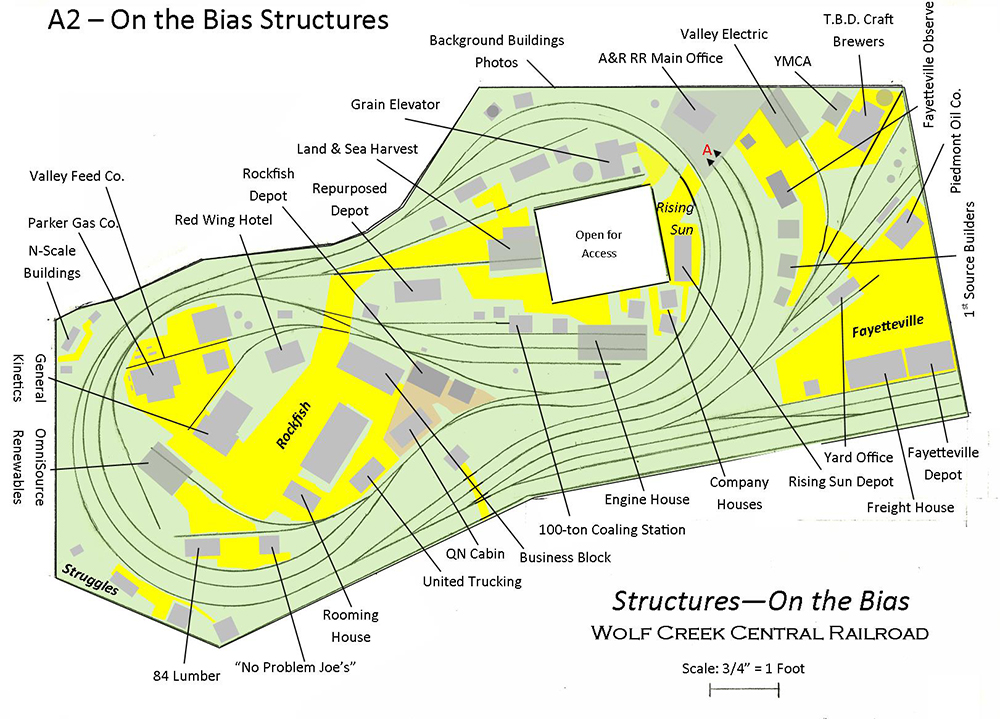

One of John’s two designs was “The Central Minnesota Railroad,” a tabletop railroad with 24-inch minimum radii. My railroad room was too narrow for an HO-scale railroad with its axis canted at 45-degrees. To make the best of John’s proposal, I altered the footprint into a dogleg configuration – one portion tipped at approximately 11.5 degrees, with the remainder bent to 25 degrees. The layout measures 13 ft. 1 in. long, by 8 ft. 1 in. wide.

A few years ago I visited the Aberdeen & Rockfish Railroad in the southeast U.S. [Model Railroader magazine ran a feature on the A&R in its November 1965 issue]. The versatile 50-mile A&R shortline offers both modeling and operational variety to satisfy almost any need. The A&R’s small-town/big city personality carried over to my model of the Wolf Creek Central R.R.

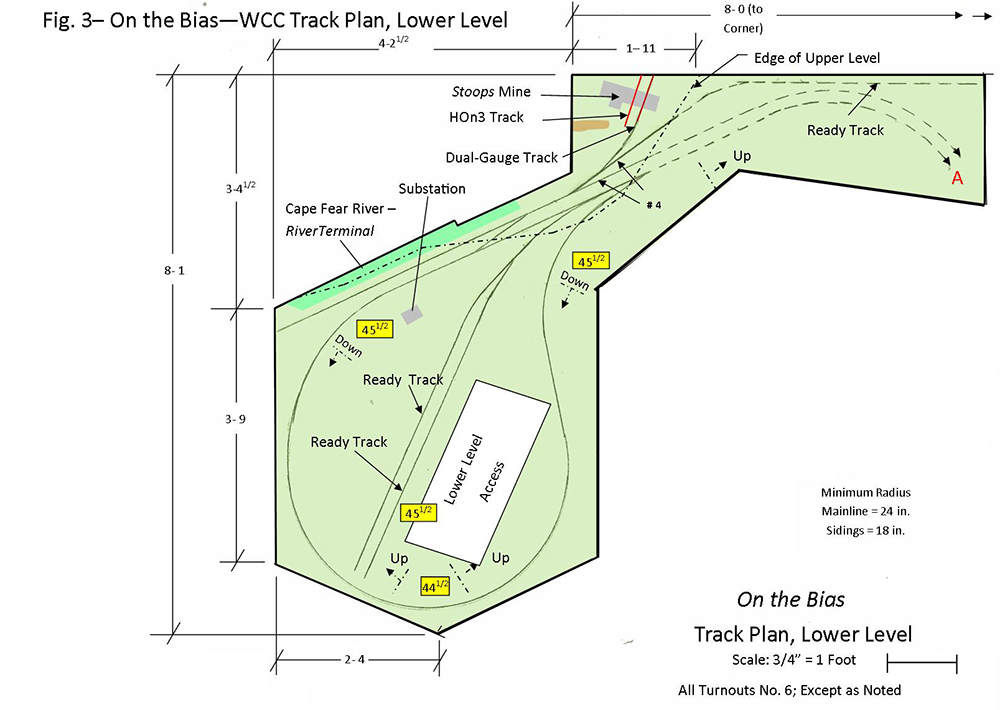

The daily out-and-back activity of the Aberdeen & Rockfish makes a lot of sense. Moving goods for pick-up and delivery satisfies customer requirements and gives a business purpose. John’s Central Minnesota’s turntable was replaced with a Fayetteville industrial park on the Wolf Creek Central. The mainline from Fayetteville continued to one of the major features (and centers of activity) on the Aberdeen & Rockfish: River Terminal, along the headwaters of the Cape Fear River.

River Terminal does duty as a “universal interchange.” Barges tie up to either receive or offload goods. While almost anything can travel by barge, commodities handled at River Terminal are mainly grain, lumber, coal, and petroleum products. I added a balloon track (reverse loop) at River Terminal to allow for turnaround and return to Fayetteville. The River Terminal also offers some not-too-obvious operating considerations. On the WCC ,empty cars for receiving materials at the riverfront need to be requisitioned in advance from the most appropriate of the three connecting railroads. They can be parked at a “ready track” or at one of the interchange tracks on the layout. After loading at River Terminal, cars are routed either on-line or off-line via interchange.

The Cape Fear riverfront, with its space-eating balloon track, caused a demand for more real estate. John’s original flat, table-top, concept became more complex. A grade was run from Fayetteville down to River Terminal, with its ready tracks and the balloon track. The mainline’s end-to-end running length grew to 81 feet.

The Aberdeen & Rockfish RR meanders approximately 50-miles, west-to-east, from Aberdeen, NC, to Fayetteville, NC. The town of Raeford sits midway along the line. Between Raeford and Fayetteville lies Dundarrach. At Dundarrach the railroad makes a sharp turn to the north on an 8-degree curve. In the past, a sawmill received rail service at Dundarrach. The sawmill is gone, but the sharp curve remains on the A&R. I kept the curve and added a whistle stop named “Struggles.” River Terminal is approximately one mile beyond Fayetteville. While the A&R general offices and engine terminal are back at Aberdeen, the majority of railroad business transpires at Raeford, Fayetteville, or River Terminal.

Three common carriers interchange at the end-points of the A&R. On the west end, at Aberdeen, the Aberdeen, Carolina & Western and CSX touch base and trade cars. Fifty miles, or so down the line at Fayetteville, Norfolk Southern makes a visit. The Wolf Creek Central includes an interchange track for each of these three railroads. There are hidden “ready tracks” to park cars or short trains of CSX, AC&W, and NS, ready for interchange.

The casual observer may note that the WCC has no staging tracks. The underlying logic for this omission is: one does not usually find foreign traffic running end-to-end over the Aberdeen & Rockfish. A&R power typically pulls short trains to serve its many customers. It would be unusual for, say, a CSX or an NS train to appear at Aberdeen or Fayetteville to make a run across the line. The three “ready tracks” that bring cars for trade on the WCC work just fine.

On the Wolf Creek Central, the main features of the A&R remain intact; only the names have changed. Aberdeen, with the A&R General Offices and engine terminal, is now Rockfish. Raeford is Rising Sun. Dundarrach is now Struggles. Fayetteville remains as Fayetteville; River Terminal is still alongside the Cape Fear River.

There are three distinct plateaus on the WCC: River Terminal, Fayetteville, and Rockfish. Short grades connect the three levels. Grades are approximately 2.7%. There is 20” of vertical easement into and out of each grade. Grades are typically 2.5% on the hilly A&R. The model railroad is therefore not too far off base. The actual lowest elevation on the WCC is below River Terminal and the corresponding Cape Fear River. A 1” dip on the balloon track, below the finished grade above, gave room for a 24″ minimum radius.

Flextrack for the WCC has been salvaged from previous layouts. The track is a mix of code 100, code 83, and code 70. The code 100 was used on hidden tracks and in the River Terminal region. Track is either code 88 or code 70 in the remaining visual areas. There are six curved turnouts, a No. 6 double-slip switch, and a No. 6 three-way.

The longitudinal L-girders and the 1 x 3 framing were also salvaged from previous layouts. I did purchase new Homasote and ½” plywood for this layout’s flat surfaces. The Homasote is screwed to the plywood from below. Flex track and turnouts are spiked directly onto the Homasote – no roadbed. After a decent application of ballast, the finished track is presentable.

A 60-lb. capacity caster is screwed to the bottom of each of the layout’s six legs. The casters were also salvaged from an earlier layout. Later I found that the salvaged casters are too small. I should have invested in 100 lb. capacity casters.

The majority of the turnouts are hand thrown via Caboose Industries ground throws. For remote control of other turnouts, there are 12 Tortoise and 8 double-coil switch machines. Four Tortoise switch machines run the turnouts in the center of the layout at Rockfish, four for the double slip and the crossover at Fayetteville, and four more for the ladder track at the head of the Fayetteville yard. At River Terminal I used six twin-coil switch machines on code 100 turnouts.

The layout is controlled by Digitrax DCC using the DB150 command station with a hand-held radio throttle. A decoder programming track is near the Fayetteville depot. On the main control panel a heavy-duty DPDT switch toggles the layout between either “Run” or “Programming.” Another DPDT switch on the panel allows for the entire railroad to change from DCC to 12V DC for troubleshooting. The layout is divided into four electrical blocks. The balloon track and the yard in downtown Rockfish are auto-reversing zones and are also two more electrical blocks.

Except for the scratchbuilt Rising Sun depot, all the structures were built from kits. Most have some degree of kitbashing and weathering.

A four-cycle car forwarding system is used for operation. It works well with the short sidings of the Wolf Creek Central. Short trains of up to five cars are more than practical.

The “reach” to the center of the layout at Rockfish is a little more than recommended by John Armstrong. There is little to operate out in the middle of town, though, so the reach-in distance is tolerable.

The moderate size of the Wolf Creek Central pike presented everything that I wanted. The bias footprint offered special challenges that made it interesting but fun to build. I believe John would be pleased to know that someone actually did build a layout designed “on the bias.”

Meet Jon Fruth

Jon is a member of the C&O Historical Society; Kokomo, Ind.’s Midwestern Model Railroad Club; the Nickel Plate Historical & Technical Society; and the Fostoria, Ohio, Rail Preservation Society. Jon grew up in Fostoria’s “Iron Triangle” and was forever bitten with the railroad bug. Jon and his wife, Jean, live in Kokomo. Jon also enjoys hiking and bicycling.