Milwaukee Road Hiawatha passenger trains are the long-lasting legacy of a Midwestern railroad plagued with underperformance and mismanagement — right up until its merger with the much smaller Soo Line in 1986. Rather than recount the bad times, join us for a look back at the Hiawatha trains over the years. Only from Trains.com.

Twin Cities Hiawatha

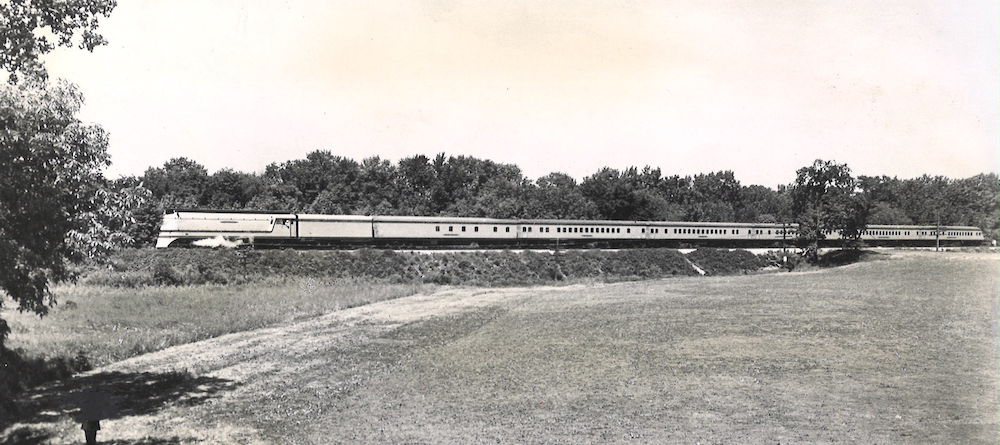

It was the first, it was the flagship, and it was fast. The original Hiawatha passenger train zipped into service between Minneapolis, Milwaukee and Chicago on May 29, 1935, to help the Milwaukee Road leave both the Great Depression and its competitors in the dust. The iconic orange-and-maroon streamlined speedster, from the shrouded 4-4-2 Atlantic-type steam locomotive to the “beaver tail” observation car, became a breath of fresh air along the system’s upgraded main line of 90-plus miles per hour.

The chosen name, “Hiawatha” was inspired by the indigenous American whose legend through Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem relates of outrunning an arrow. In later years as the Twin Cities Hiawatha, the service grew to two trains a day as a Morning and Afternoon Hiawatha, while usually receiving the latest equipment. It was the genuine flagship all the way to the very end of passenger service in 1971. The train’s highspeed success and popularity led to the Hiawatha brand being adapted on the railroad’s other passenger services to enhance the image and business.

North Woods Hiawatha

In June of 1936, the Hiawatha – North Woods Section was inaugurated on the Milwaukee Road’s Valley Line between New Lisbon and Minocqua, Wisconsin. While connections were made with the Twin Cities Hiawatha at New Lisbon, the North Woods Section only reached maximum speeds of up to 55 mph. Despite not replicating the quick service its speedy counterpart produced, the train’s early success still justified the extension between Chicago and Star Lake, Wis., by way of New Lisbon, in the summer of 1939.

The North Woods Hiawatha became known as the “fisherman’s friend” with its primary passengers being tourist to the state’s North Woods, and fisherman heading to the lakes around the areas of Tomahawk, Minocqua, and Star Lake. Station stops were also made at resort entrances or depots serving fishing camps instead of established communities. With better roads providing easy access to northern Wisconsin, the name of the North Woods Hiawatha was quietly eliminated on April 29, 1956, when the service was shortened as far north as Wausau, Wis.

Chippewa-Hiawatha

The Milwaukee Road’s secondary line from Milwaukee north to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula reached smaller communities while bypassing more populated areas with the exceptions of Green Bay, Wis., and Iron Mountain, Mich. That didn’t stop the railroad’s continuous expansion in the Hiawatha branding. On May 28, 1937, the Chippewa was put into service between Chicago, Milwaukee and Iron Mountain, later extending to the Lake Superior shores in Ontonagon, Mich. While not picking up the Hiawatha name until 1948, it was more or less a fast streamlined train from the very beginning, with a shrouded 4-6-2 Pacific-type steam locomotive leading mostly light-weight passenger cars and cutting the run time by two hours. It was a short-lived Hiawatha as the name was dropped from the Chippewa in April 1957, reflecting the drop in popularity for passenger trains at that time.

Midwest Hiawatha

Much like the route of the Chippewa-Hiawatha, the Milwaukee Road’s other secondary line from Chicago to Omaha, Nebraska was considered uncanny for avoiding populated communities in between. That didn’t stop the Midwest Hiawatha from making its first run at a maximum 70 mph on December 7, 1940, between Chicago, Omaha, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Both the Omaha and Sioux Falls sections of the service would either split or combine at Manilla, Iowa in each direction, making it a double-destination train. The Midwest Hiawatha was well received at the time for operating a reasonable daytime schedule.

By September 1955, the Milwaukee Road began handling all streamlined passenger trains of the Union Pacific Railroad east of Omaha. This resulted in the Midwest Hiawatha and the Chicago-Los Angeles Challenger from UP being combined into the Challenger-Midwest Hiawatha. The later combination of the Challenger and City of Los Angeles in the spring of 1956 resulted in a nighttime schedule on the Milwaukee Road and ultimately ending the Midwest Hiawatha.

Olympian Hiawatha

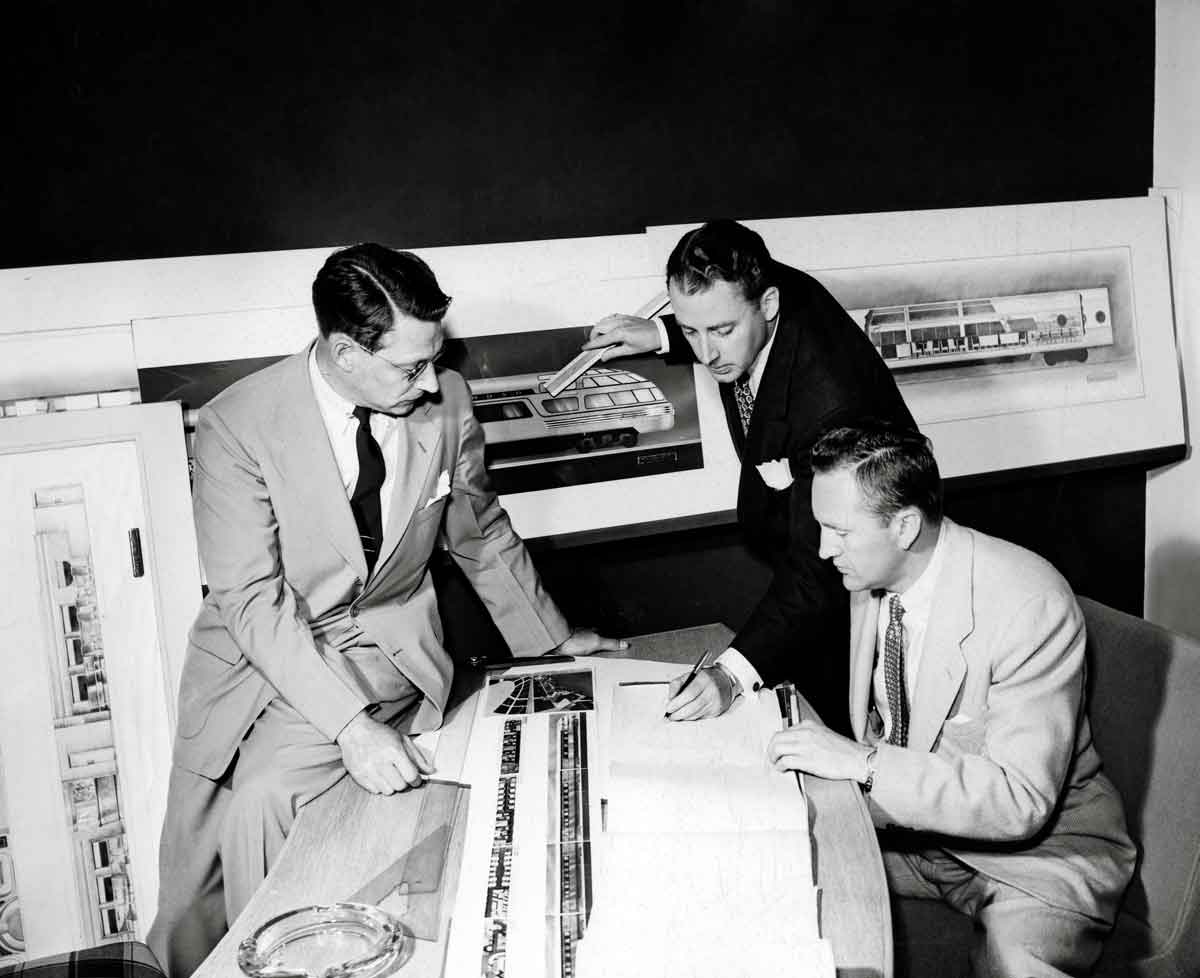

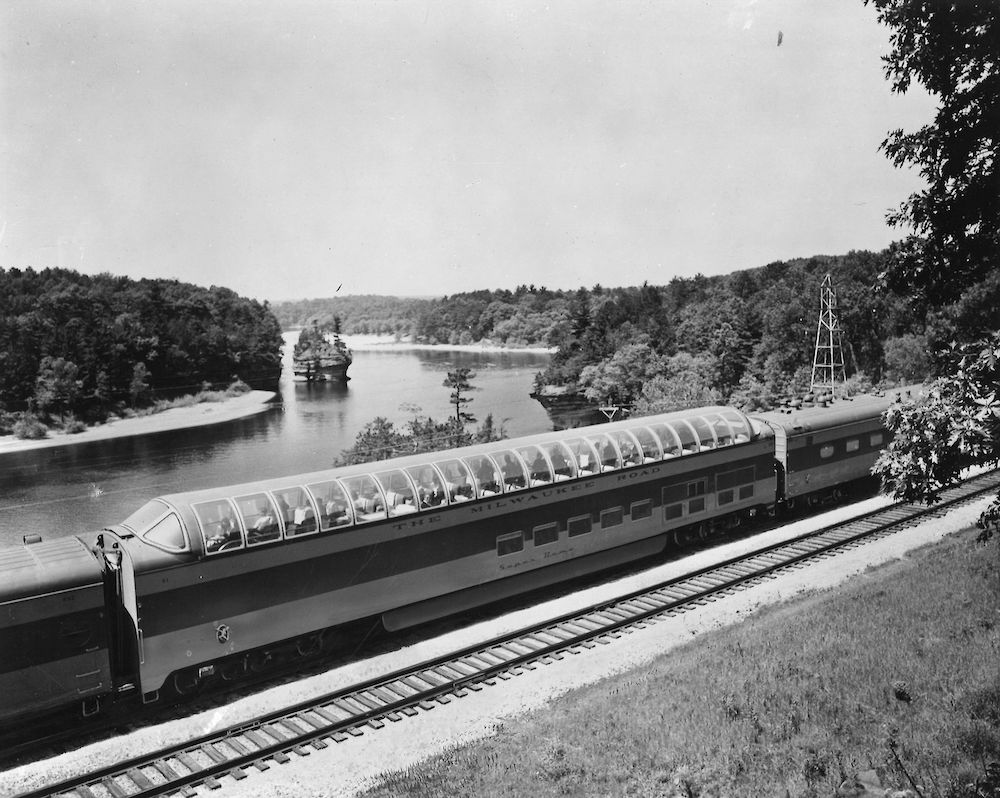

While the Chicago-Seattle-Tacoma, Washington Olympian was around long before the original Hiawatha hit the rails, it wasn’t until June 29, 1947, when it too received the Hiawatha treatment. In competition with the Great Northern’s Empire Builder and Northern Pacific’s North Coast Limited, the Milwaukee Road’s Olympian Hiawatha aimed to break the mold with industrialist designer, Brooks Stevens as an ally.

The postwar streamliner introduced quality passenger and sleeper accommodations from Pullman-Standards with designs of larger dimensions than the original Hiawatha cars. This was followed by Steven’s unique Skytop Lounge bedroom-observation cars. Super Dome, the very first full-length dome car on the Milwaukee Road, provided a 360-degree panoramic view when introduced on the train in 1952. From 1947 to 1961, the Olympian Hiawatha traversed the railroad’s Pacific Extension through the Rocky and Cascade mountains.

Amtrak

On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over nearly all the nation’s passenger rail services, including what was left operating on the Milwaukee Road. The main line that was once the stomping grounds for the Twin Cities Hiawatha today sees Amtrak’s long-distance Empire Builder between Chicago and Minneapolis, while the Hiawatha corridor service provides a quick commute between the Windy City and Milwaukee. These modern passenger trains may not be like the old days when a flash of orange and maroon from the Midwest to the Puget Sound was common. However, they help carry on the memory, legacy and spirit of the Milwaukee Road Hiawatha passenger trains.

The Touralux Tourist sleeping cars, including a short-lived combo Women/Children coach/8-section sleeper, should not be overlooked. Lightweight Tourist sleeping cars were an attraction and a rarity.

Having lived in the 1950s for 3 years in Chicago a block from the Milwaukee’s route northwest out of Chicago–and getting daily views of the Morning, Afternoon and Olympian Hiawathas as they speeded out of town–and then for 2 years in little suburban Bartlett with its daily visits from the Midwest Hiawathas, I still wonder how an “underperforming railroad” could have managed to field such a magnificent roster of passenger trains.

Excellent article

It still blows me away that not one Hiawatha Locomotive was saved.