Mind-blowing beer and train facts

Beer arrived first, but the railroads helped this favorite beverage grow to national prominence. The beer in your glass, however, is not the whole story. Throughout history there are many twists and turns in the relationship between beer and trains. Here are five mind-blowing beer and train facts.

No. 1: The real Coors Light Silver Bullet train

In April 2011, Molson Coors Canada, working with VIA Rail, fielded a real Coors Light Silver Bullet train for an excursion party through the Canadian Rockies. Departing from Edmonton, Alberta, the 100 lucky passengers (contest winners) were treated to great scenery and on-board amenities like an arcade car, a “sports” car, a cinema car, and the Neon Boxcar, the ultimate Coors Light nightclub on rails.

VIA Rail provided a pair of F40PH-2s for power. The locomotives were graphically wrapped to resemble the animated locomotives seen in Coors Light television commercials.

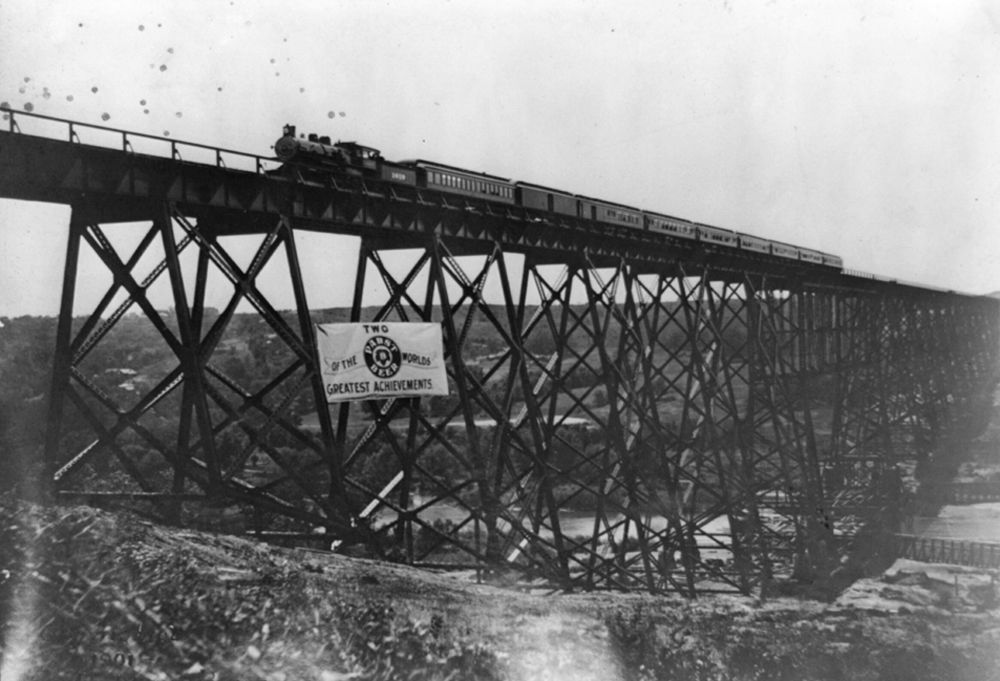

No. 2: F.&M. Schaefer Brewing and Grand Central Depot-Terminal

In January 1850, Friedrich and Maximilian Schaefer moved their prosperous brewery to the corner of Park (Fourth) Avenue and 51st Street, New York. As part of the construction, they excavated a lagering cave 30 feet wide and 250 feet deep. The new cooling facility was to hold a double row of beer casks. By 1871, Schaefer would be the eighth-largest U.S. brewer, rolling out more than 43,000 barrels annually.

The F.&M. Schaefer brewery also enjoyed the services of the New York Central and Harlem River Railroads. The railroad tracks came right up to the west side of the brewery at street level along Park Avenue. Receiving grain and other materials by rail couldn’t be more convenient.

In 1871, few blocks south at 42nd Street, the New York Central; New York, New Haven & Hartford; and Harlem River Railroads opened Grand Central Depot. The new station sent passenger traffic in Manhattan on an upward trajectory. It also sent citizens complaining about the number of trains and accidents occurring on Park Avenue.

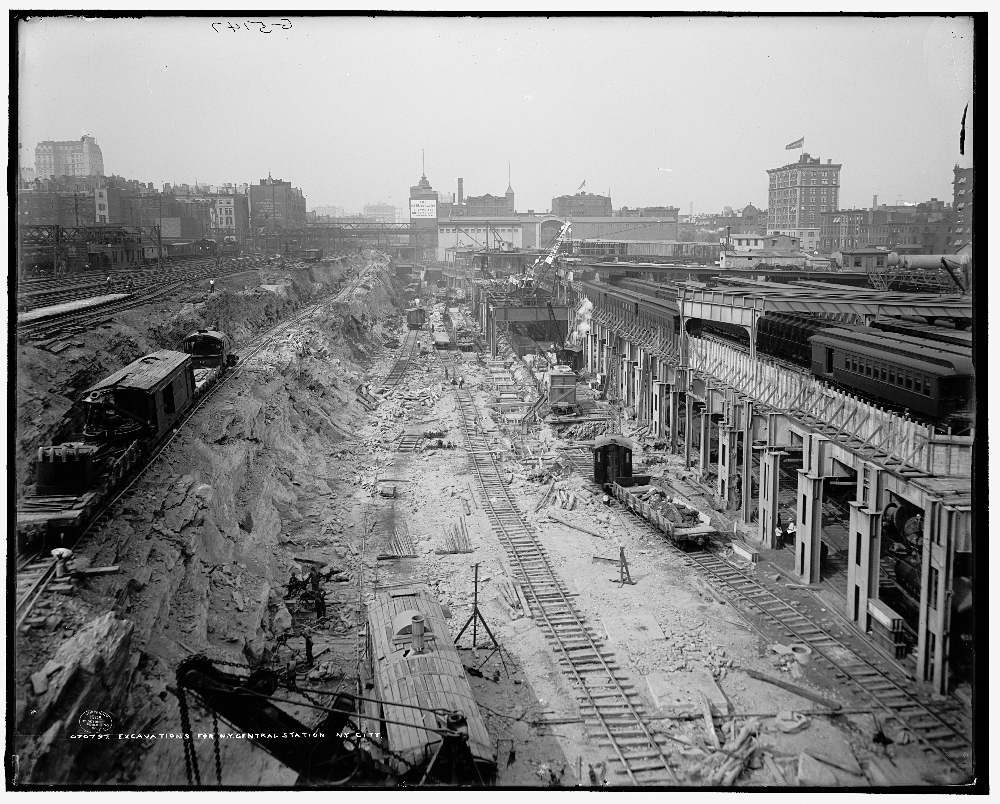

By the late 1870s, the situation had reached its breaking point. The solution: The tracks had to go. Building up was not an option; going down, however, held promise, so the tracks went underground. Over the next 30 years, several waves of railroad construction radically altered Park Avenue.

Digging this subterranean rail route required several million cubic feet of dirt and rock to be excavated. Although the Park Avenue area was a less-than-desirable section of town, as opposed to its contemporary high-profile status, there were some concerns over existing structures when the steam shovels and cranes pitched in. One of those was the F.&M. Schaefer brewery and its lagering cave. In the construction, Schaefer lost its street-level rail spur. Although there were concerns on both sides about hitting or damaging the lagering cave, little damage was done. The below-street-level, passenger-car holding yard ended right across East 50th Street from the brewery.

By the time Grand Central Terminal opened on Feb. 2, 1913, Park Avenue was well on its way to being a fashionable residential address. The factories along Park Avenue, including F.&M. Schaefer, had to go. In 1916, the brewery moved its operations to Brooklyn, selling its Manhattan property. One block front became the Ambassador Hotel, the other St. Bartholomew’s Church. The land sale netted the brewery significant cash for its new plant.

No. 3: What’s in a name?

At the dawn of the 20th century, Pabst was clearly a recognized name. When Johann Gottlieb Friedrich Pabst arrived in America, he had not a penny to his name. He grew his brewing empire to one of the largest in the nation, and from its proceeds built a comfortable life for his family and enriched his community. To say that Pabst was well respected is an understatement.

As Christmas 1903 approached, the health of Captain Pabst was beginning to fail. The family gathered to celebrate the holiday with as much festivity as possible. In the week following Christmas Gustave Pabst, the eldest son, and his wife Hilda traveled by train to visit her parents in St. Louis.

As New Year’s Day approached Captain Pabst took a turn for the worse. With family at his side, he died on Jan. 1, 1904, at 12 p.m.

Word was sent for Gustave and Hilda to return to Milwaukee immediately. A private train was quickly chartered and left St. Louis late in the afternoon on Jan. 1. The grieving couple arrived in Milwaukee at 12:30 a.m., Jan. 2, 1904. The trip was made in near-record time.

No. 4: Your beer, Pullman style

Pullman porters and waiters had strict rules detailing the procedure for serving a beer. It was all about good service — the same type of service to be expected in a fine restaurant or club. Pullman’s 1939 Commissary Instructions, a pocket-sized book issued to all chefs, waiters, busboys, and ground personnel, included a plethora of detailed instructions. Along with rules on how to handle meal checks, proper uniform, cocktail recipes, and how to serve popular menu items, could be found the 12 steps required to serve a beer.

Beer

- Ascertain from passenger what kind of Beer is desired.

- Arrange set-up on bar tray in buffet: one cold bottle of Beer, which has been wiped, standing upright; glass (No. 11) 2/3 full of finely chopped ice (for chilling purpose — making it a distinctive service); glass (No. 12); bottle opener; and paper cocktail napkin. Attendant should carry clean glass towel on his arm with the fold pointing toward his hand while rendering service.

- Proceed to passenger with above set-up.

- Place bar tray with set-up on table (or etc.).

- Place paper cocktail napkin on table in front of passenger.

- Present bottle of Beer to passenger displaying label and cap. Return bottle to bar tray.

- Pour ice from chilled glass (No. 11) into glass (No. 12).

- Open bottle of Beer with bottle opener in presence of passenger, (holding bottle at an angle) pointing the neck of bottle away from passenger; wipe top of bottle with clean glass towel.

- Pour Beer into glass (No. 11) by placing top of bottle into glass, and slide the beer down the side until beer reaches about 2 inches from the top — then put a collar on the beer by dropping a little in the glass which now should be upright.

- Place glass containing Beer on paper cocktail napkin.

- Place bottle containing remainder of Beer on table before passenger, with label facing him.

- Remove bar tray with equipment not needed by passenger and return to buffet.

No. 5: Adolphus

Adolphus Busch — think Budweiser — spared no expense when it came to enjoying the finer things available to those with means during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Busch maintained two homes in St. Louis, two more in Pasadena, Calif., a hop farm and retreat outside Cooperstown, N.Y., and two villas around Langenschwalbach, Germany.

To conduct business and visit his properties, Busch owned and traveled aboard a private Pullman car. The car, named Adolphus, was presented to him in the early 1900s by the brewery’s board of directors in appreciation for building the brewing empire bearing his name.

Without saying, the Adolphus was appointed with all form of luxuries to ensure comfort while traveling. Busch also had an office aboard the car. It was stocked with records and notes identical to his office at the brewery so that business could be conducted on the road. At the St. Louis brewery, Adolphus was stored inside its own facility. When Busch returned to the brewery aboard his car, a cannon war fired to herald his arrival.

Anheuser-Busch Co. had a second Adolphus in the 1950s. Built by the Wabash at their Decatur, Ill., shops, the car was used by August Busch Jr. until it was sold in 1965.

I love this train article about railroad and their involvement with beer.

Unfortunately, this has not changed my distaste for beer and all who overindulge.