Track type and uses: Understanding prototypical trackwork and operation is essential to building an accurate model railroad. Of course, strictly prototypical operations and layouts are not the goal of every model railroader, but an understanding of prototype trackwork and its model counterparts is nonetheless imperative for those modelers wishing to deviate from prototype to ensure smooth and enjoyable operations.

Rail

Let’s start with track structure: after all, what Is a model railroad layout without the railroad? Track structure is composed of a few essential parts: rails, ties, and hardware. The standard track gauge, or in other words, the width between the interior edges of the rails, in North America is 4’-8½”.

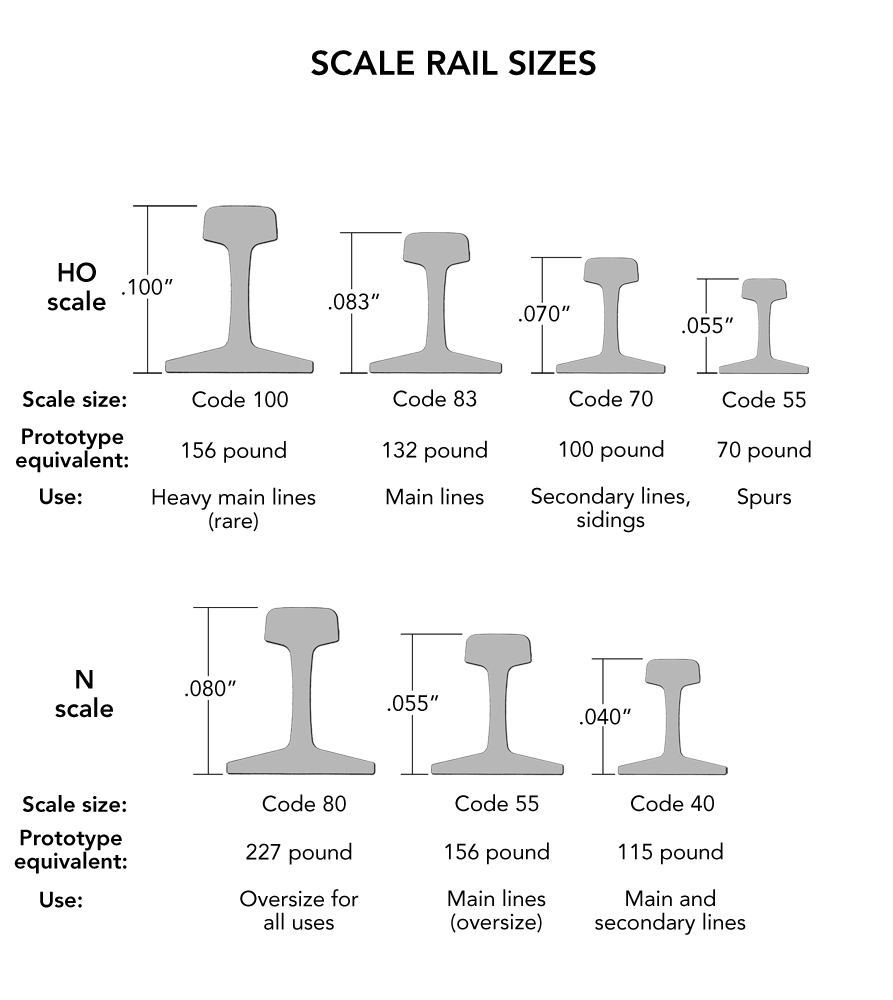

In model railroading, scale rail “Codes”, which refers to the height of the rail as measured in thousandths of an inch, correspond with a prototype-equivalent rail type. HO scale Code 100 track, for example, which measures .100” in height, corresponds to 156 pound prototype equivalent rail, typically used for heavy main lines. N scale Code 40 rail, which measures .040” in height, corresponds to 115 pound prototype equivalent rail, often used in both main and secondary lines.

Ties

As one may infer from the name, ties hold the rails together, keeping them at the appropriate gauge. Additionally, their wide stance allows for better displacement of weight from locomotives and cars. Ties are typically constructed from one of two material: wood or concrete.

Wooden ties are inexpensive and flexible, which means when overloaded, they bend, rather than break. However, they are more susceptible to deterioration than their concrete counterparts.

Concrete ties, conversely, are stronger than their wood alternatives, but rigid, meaning that they are more prone to cracking. They are also more expensive per-unit than wooden ties, but the tradeoff is their resistance to weathering which wooden ties are prone to means they will need to be replaced less frequently, theoretically negating a cost difference in the long-term. Concrete ties are also spaced further apart than wooden ties, meaning fewer total ties are needed on a given line.

Scale rail manufacturers more often focus on modeling wooden ties, as they are the de facto of eras most frequently chosen by modelers. Of course, scale concrete ties are still produced.

Turnouts

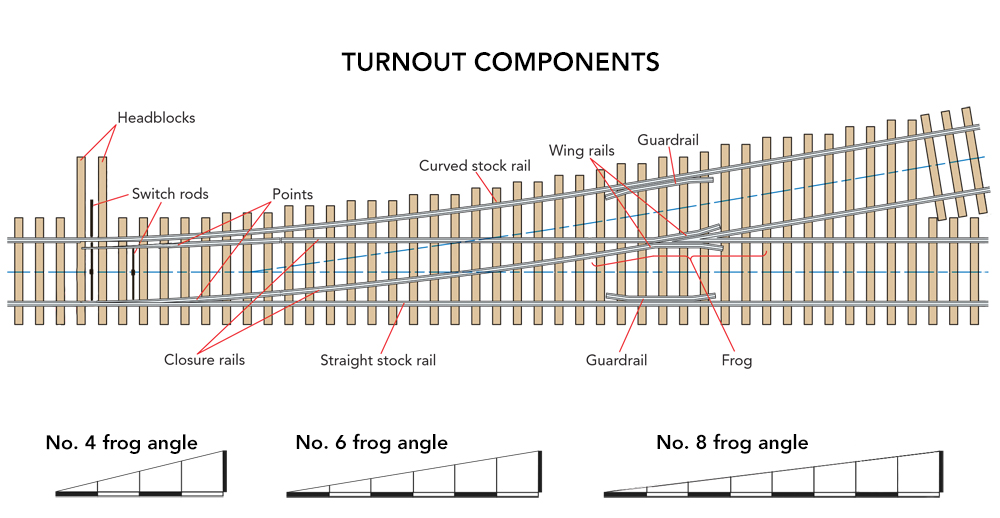

Turnouts open alternative routes for your trains. If you wish to model something other than a loop, you’ll need turnouts. Prototypically speaking, the split-point turnout has been the standard since the late 1800s. This design features a set of moving rails which guide trains into different available routes. Stock rails constitute the diverging “routes.” The frog is the meeting point of the inner rail of each stock route, which forms an “X.”

Often times, the terms “switch” and “turnout” are used interchangeably, but in reality, they refer to separate things. Prototypically, the switch refers to the moving elements of the turnout which changes the routes, whereas the turnout is the entire track component itself.

In prototype operation, there are manual and remote turnouts. Similarly, in model railroading, there are powered turnouts, typically controlled by a switch machine under the layout, and manual turnouts, operated with a simple lever or slide on the layout itself.

Most model turnouts produced feature wooden ties. Prototypically, wooden turnouts are the industry standard. Their flexibility, compared to the concrete alternative, offers better reliability, and they are more cost effective to produce.

Switch stands and targets

A switch stand is a manual device mounted to a headblock which moves the points and holds them in position, and in turn facilitates the changing of routes.

Model switch stands, like the one shown above, come in two varieties: functioning and non-functioning. It’s not uncommon for functioning switch stands to break scale to ensure reliability and durability. Non-functioning switch stands do not require these qualities, at least not to the same degree, as they serve a purely aesthetic role on your layout, and are better able to adhere to scale.

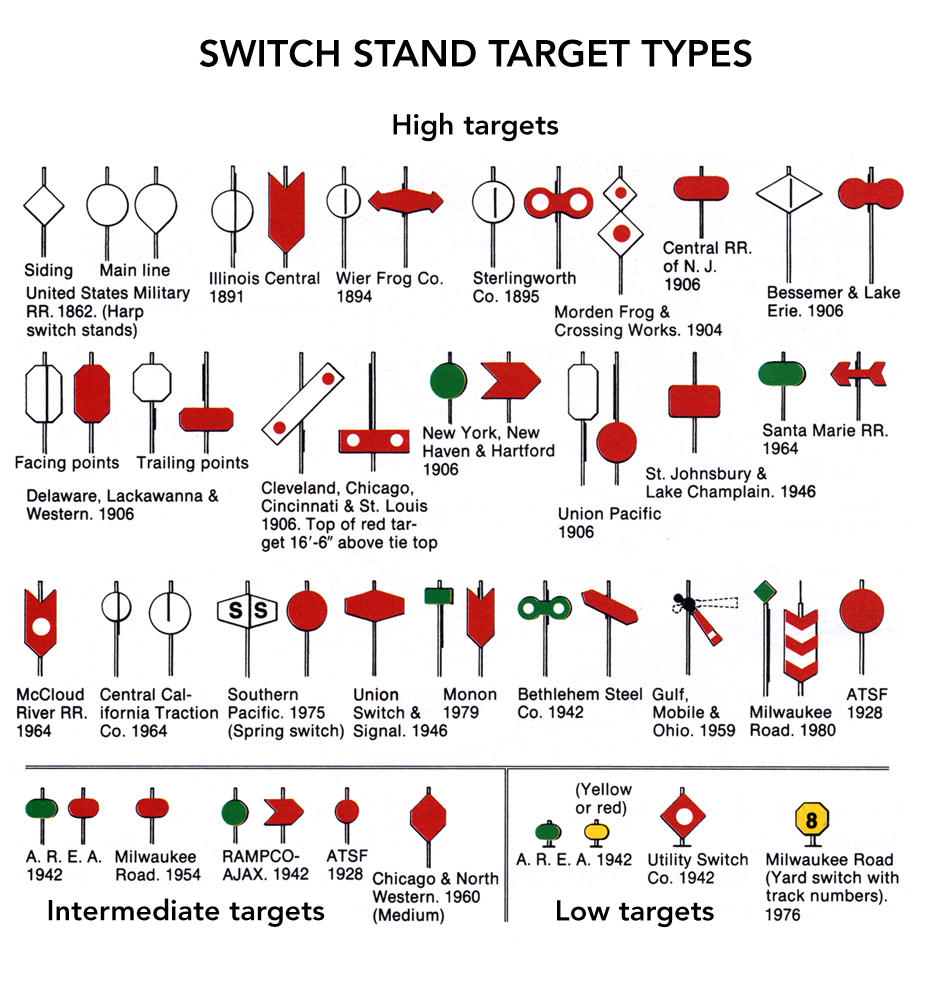

Often, switch stands utilize signage known as targets. These targets serve as a sort of traffic indicator, alerting the crew of a given train on a given line as to which route they are following. These targets typically rotate 90 degrees showing either a target indicating the main route, typically depicted in green or white, or the alternate route, usually shown in red.

Crossings

Crossings, as the name would imply, allow two separate lines to cross without merging or changing routes. Like turnouts, the rails of the individual routes join at four frogs, but unlike turnouts, crossings do not feature switches, as the routes are set and do not merge.

Mainline crossings require traffic control, as the higher speeds of these routes offer the potential for collision. In yards and leads, crossings do not always require traffic control due to the lower speed.

Bumpers

Much like a real railroad, the ends of your track, be it an industrial spur, a yard track, or just a stub-end, require a bumper to prevent your trains from rolling off. Take a look at one and you’ll quickly understand how they work.

Bumpers are an essential detail to industrial and yard layouts. Typically, in heavy usage areas, heavy-duty bumpers like those shown above are used.

On less-frequently used tracks, these heavy-duty bumpers can be substituted for wheel stops placed on the rails, or even a pair of ties, crossed over the rails with one end buried in ballast.

An understanding of prototype operations and trackwork is a great foundation for any model railroader. However, prototypically accurate operations and layouts are not the goal of every railroader, nor should they be. After all, this hobby offers much more than the replication of prototype at scale, and that’s what makes it so great; there’s something for everyone.