Soo Line history involves numerous subsidiary railroads.

Seemingly hidden away in the north-central U.S., the Soo Line and its affiliated Wisconsin Central Railway did not receive the attention lavished on bigger neighbors Chicago & North Western and Milwaukee Road. Soo did not host a streamliner, went freight-only in 1968, and was bought by Canadian Pacific, which long had controlled it, in 1990. Soo public relations man Wallace W. Abbey chronicled the railroad in his 1984 book, The Little Jewel, a title meant to evoke its ability to generate profits for CP but apropos in many other ways.

Yet Soo left a big mark in railroading. In 1960, it merged the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie, the WC, and the Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic, another CP-controlled regional, into what it called the “New Soo.” Like the Monon, it adopted its popular monicker as its official name: Soo Line Railroad (“Soo” being the pronunciation of “Sault”). Before and after the merger, Soo proved you could make a profit in territory where others struggled. It did so through conservative management of its limited resources and an emphasis on customer service.

Soo Line history dates to the Sept. 29, 1883, incorporation of the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Atlantic. It was the brainchild of Minneapolis milling interests anxious to find a way to ship their products east without going through the expensive and congested Chicago terminal. The millers’ answer was a direct 500-mile line from Minneapolis to a CP connection at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Construction began in April 1884 at Cameron, Wis., and “the Sault” (two like-named cities in Michigan and Canada) was reached in December 1887. Originally the road reached Minneapolis by trackage rights on the Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha from Turtle Lake, Wis. This was remedied when a subsidiary, Minneapolis & St. Croix, was built from Turtle Lake into Minneapolis, and the route opened in January 1888. Simultaneously the Minneapolis interests incorporated the Minneapolis & Pacific to build west to bring wheat from the Dakotas to the Twin Cities’ mills.

Like many rail ventures of the era, all three encountered financial problems, but CP propped them up, mandating they be consolidated. Thus began Soo’s long relationship with Canada’s first transcontinental railway, as on June 11, 1888, the MStP&A, M&StC, and M&P were joined to form the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie Railway. The nickname “Soo Line” quickly emerged.

The “first” WC in Soo Line history

Wisconsin Central Railway was incorporated Feb. 4, 1871. Ground was broken June 15 at West Menasha (now Neenah) for a line to Stevens Point. It would reach Ashland, on Lake Superior, in 1877, and WC was granted nearly 1 million acres of land for finishing the line. WC reached St. Paul in 1884, Chicago in 1886, and Superior in 1908.

WC seemed to be an “also ran,” though, as its routes were longer than its competitors’. In 1889 the transcontinental Northern Pacific contracted with WC to handle its trains from St. Paul to Chicago, and in 1890 NP leased the WC. NP subsidiary Chicago & Northern Pacific built Grand Central Station in Chicago that year, and for a time operated Chicago suburban trains. NP entered receivership in 1893, however, and defaulted on its WC lease payments, ending its control. Baltimore & Ohio would buy Grand Central in 1910 and be its majority user.

Soo Line recognized the value of WC’s routes and in 1908 acquired a majority interest, then leased the property on April 1, 1909. Under the agreement, WC remained a separate entity and Soo did not participate in its profits or losses, nor did it pay rent. However, the roads gained traffic from each other, and WC gave Soo access to Chicago. Although the combined system was known by the Soo Line name, WC continued a separate existence with its own officers and stockholders until the 1960 amalgamation. For trackside observers, ownership of locomotives was easy to spot, as WC’s had four-digit numbers but Soo’s just three digits. Steam-engine tenders wore the “dollar sign” Soo emblem, and diesels’ flanks had “SOO LINE” spelled out, with tiny W.C. initials. This practice also lasted until 1960. WC would remain a Soo ward for 52 years, though the lease ended in 1932 with WC’s bankruptcy.

Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic was incorporated in 1887 and consolidated several iron-ore roads in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Spanning from the Twin Ports of Duluth-Superior to Sault Ste. Marie, “The South Shore” had branches tapping the copper-rich Keweenaw Peninsula beyond Houghton-Hancock and to St. Ignace on the Straits of Mackinac. From there, carferries connected with Mackinaw City on the Lower Peninsula. DSS&A came under CP control in 1890.

The “New Soo” emerges

Upon the Dec. 31, 1960, merger that created Soo Line Railroad Co., former DSS&A President Leonard H. Murray took the helm. Known for being frugal, Murray held the presidency until 1978. A master of using the minimal resources at his disposal, he continually improved Soo’s revenues while controlling costs and increasing traffic.

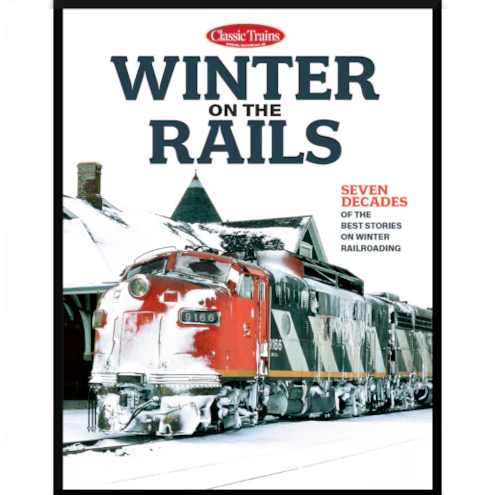

Soo invested heavily in its physical plant, installing welded rail on grain branches as well as main lines, expanding CTC signaling coverage, and purchasing new equipment. Soo also adopted a colorful new image designed by Abbey: a white (actually light gray) with red ends and black lettering on the diesels, and various colors on freight cars.

In 1980 Soo remained profitable but had some catching up to do. Its track was good, but it held trains to a maximum 40 mph systemwide, hardly competitive. As other roads negotiated labor agreements with reductions in crew size, Soo didn’t move until the late 1980s. Meanwhile, Soo had become a small road in a sea of larger players as other roads were expanding or merging. To survive, Soo had to expand its traffic mix and reach new gateways to garner longer hauls and market share. Kansas City was a logical target, and upon the Rock Island’s 1980 shutdown, Soo made an aggressive move to buy RI’s Twin Cities-K.C. “Spine Line.” In June 1982, Soo acquired the 77-mile Minneapolis, Northfield & Southern to connect with the Spine Line, but the North Western was awarded the RI route.

Soo then put its resources into buying the Milwaukee Road, which in 1980 had retrenched to a 3,100-mile Midwest “Core System.” It appeared C&NW would win the bidding war, but on Feb. 9, 1985, U.S. District Court Judge Thomas R. McMillen, who was handling Milwaukee’s bankruptcy, awarded it to Soo despite its bid of $570 million being below C&NW’s. McMillen said Soo’s bid was more in the public interest, in part because it would not abandon any lines.

Thus did it overnight, and unexpectedly, go from a 4,400-mile railroad to a 7,500-mile system, forever altering Soo Line history. It had to assume enormous debt to finance the acquisition: $187 million in cash, and $383 million of Milwaukee Road debt. The latter’s trackage mostly was substandard and required millions to become competitive. As a result, Soo began losing money. After an attempt to trim crew costs by creating the in-house subsidiary Lake States Transportation Division, with different labor pacts, on its original Wisconsin and Michigan lines, Soo in 1987 spun off those lines, plus a few former Milwaukee secondary routes, to new regional firm Wisconsin Central Ltd.

Canadian Pacific, which long had a 56 percent stake in Soo, said it would sell its interest, but in 1990 reversed course and instead took full control. Thus, while Soo still exists legally (i.e., “on paper”), and most of its original lines remain in operation by CP or Canadian National (which purchased WC Ltd. in 2001), to observers it is all Canadian Pacific. Nevertheless, while perhaps not visible and despite being under Canadian ownership, the “Little Jewel” continues to shine.