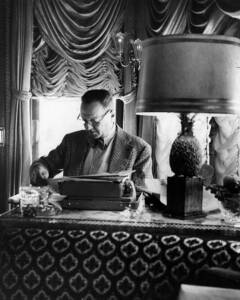

I’ve never been in the market for a private railroad car — editors and writers rarely ascend to that rarified air — but if I was, I’d compose an email this very moment and send it to the equipment broker Ozark Mountain Railcar, there to bid on what might be the ultimate PV: heavyweight sleeper-observation car Virginia City.

Fans of the writer Lucius Beebe need no introduction to the car. The Virginia City was, for many years, the property of Beebe (1902-1966) and his partner Charles Clegg (1916-1979), which meant it had a notoriety few passenger cars achieve. All you have to do is read Beebe’s marvelous book “Mansions on Rails” to see why. If I could buy the VC, I’d be sure there was always a copy in the observation lounge.

Here, in his outrageous rococo style, is Beebe’s take on the legacy of the private car:

“Seven full decades of Americans were conditioned to thinking of railroads in terms of which Englishmen had for a somewhat longer period been conditioned to thinking of ships and the sea. The private car, a microcosm of all luxury contained in limited dimensions and rolling on six-wheel trucks over the prairies and through the high passes of a limitless continent, was the sublimation of a national religion of railroading.”

And now the car once owned by the high priest of private varnish is for sale, offered via Ozark Mountain Railcar by its longtime owner and caregiver Wade Pellizzer, who has operated the car for four decades under the name Virginia City Rail Car, or VCRC. As befits a car with ties to Beebe, the Virginia City has a notable pedigree. It was constructed at the Pullman Company’s Calumet Shops in Chicago in 1928 as the sleeper/observation car Crystal Peak and initially assigned to Southern Pacific for use on the Chicago-Oakland Overland Limited (coincidentally one of Beebe’s favorite trains).

Pullman pulled the car out of service in 1936 to install air conditioning and to update the interior and renamed it Golden Peak, this time for assignment to the Golden State, SP’s Chicago-Los Angeles train operated jointly with the Rock Island. According to the VCRC website, the car was taken out of service during World War II and re-emerged briefly on Great Northern’s Empire Builder before being relegated to pool service and soon after offered for sale.

Beebe and Clegg bought the car directly from Pullman in 1954 for $5,000 and had the car hauled to the Western Pacific Railroad’s shop in Sacramento, where its interior was reconfigured and its mechanicals updated. Changes inside the car included removal of two sleeping compartments to allow for a dining room, as well as the addition of a kitchen and crew quarters from what had been a ladies’ lounge. It was presumably around this time the partners named the car for Virginia City, Nev., where Beebe owned the Territorial Enterprise weekly newspaper and had a home with Clegg.

(It’s important to differentiate the Virginia City from Beebe’s and Clegg’s other private car Gold Coast, a wood-sheathed car built in 1905 for the Georgia Northern Railway and later parked for Beebe’s and Clegg’s use in Carson City, Nev. Today it’s a gorgeous display in the collection of the California State Railroad Museum.)

The two partners put their characteristic stamp on the Virginia City. Clegg hired a friend, Hollywood set designer Robert Hanley, to redecorate the interior of the car in what VCRC refers to as “Venetian Renaissance Baroque,” or what I prefer to call “over the top.” Loaded with rich fabrics and glittering antiques, the car became, as VCRC describes it, “the most lavish and expensively outfitted car in the United States.” Having ridden in the comparatively staid accommodations of several other private cars, I’d say the claim is fair.

The car is also a battleship, mechanically speaking, in the manner of all steel cars built in the Standard heavyweight era. Here’s what Beebe has to say about that:

“An aspect of the private railroad car that at once commands attention among social historians was its durability. A 90-ton artifact of welded steel, stayed with throughbolts, braced with angle irons, riveted and annealed to withstand all but atomic concussion, was apt to be around for some time and its passage from one member of the private car club to another becomes a fascinating item of dynastic succession.”

That succession led, happily, to Pellizzer, who bought car from Clegg’s estate in 1984, embarked on a thorough restoration of the car, made significant mechanical updates over the years, and operated a slew of trips on the West Coast, mostly on Amtrak’s Coast Starlight or California Zephyr. He also retired its red, white, and blue faux Amtrak paint scheme and finished the car in handsome two-tone grey. His stewardship of the car is admirably summarized by writer and photographer Ken Rattenne on the VCRC website and in the March 2012 issue of Trains.

Truth to tell, Beebe could be defensive about private cars, going to some pains to explain that the vanish wasn’t all thatostentatious, all things considered. Not that he cared in the end. He was blueblood Boston to the core, so obvious in another passage from “Mansions on Rails.”

“Amidst the more impressive testimonials to resounding wealth evolved by the well-to-do in nineteenth-century America, the private railway car was not a conspicuously costly or ostentatious property,” he wrote. “Compared to seagoing yachts, whole blocs of Fifth Avenue real estate crowned with French chateau, hunting lodges in the Adirondacks and racing stables at Lexington and Auteiul, the private car was a modest artifact of investment. … Yet because of the hold upon the popular imagination of railroading in the (1870s) and (1880s) and the continental dimension it had achieved, no other single property ever approached the implications of prestige of the private car and its exalted status in general fancy.”

Now, someone new is destined to own the Virginia City. Let’s hope they are as good as stewards of the car as Messrs. Beebe, Clegg, and Pellizzer have been, and that the car’s “exalted status” remains intact.

You can explore the fascinating lives of Beebe and Clegg in two recent and excellent books: “Beebe & Clegg: Their Enduring Photographic Legacy,” by John Gruber and John Ryan (Center for Railroad Photography & Art, 2018); and “The Railroad Photography of Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg,” by Tony Reevy (Indiana University Press, 2019).