Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the August 2006 issue of Trains Magazine in the “Railroad Reading” section.

Recently one of my authors at Morning Sun, who is writing a Lehigh Valley book, came here and immediately stated, “I didn’t know you were once the fourth-largest shareholder in Lehigh Valley common stock.”

This immediately drew a wide grin as I realized he was onto something, but instead I replied, “Where did you come up with that?”

At that, he produced a homely looking, spiral-bound “Annual Report to the Interstate Commerce Commission for the Year ended December 31, 1973, from the Trustees of the Lehigh Valley RR.” Sure enough, on page 7, the listing of “Voting Powers of Common Stock Holders” listed: 1) Penn Central Transp. Co., 1,475,561 shares; 2) (a private individual), 3,500 shares; 3) Reich & Co. Inc., 2,100 shares; and 4) (actually tied for third place) Robert Yanosey, 2,100 shares.

Now that this is public information (at least to those who pore over arcane documents like ICC reports), the story bears telling.

In 1972, the railroad world was in a deep quandary as to the future of the five major Northeastern roads that had crashed into bankruptcy in the preceding years. As a student of railroad history, I recognized that at least the core routes of these roads were vital to the American economy and that some sort of major consolidation would eventually be worked out.

Now, common stockholders are almost always wiped out in bankruptcy reorganizations, but since the government was deeply involved and the term “nationalization” was being bandied about, I speculated that some political token might be thrown to the millions of railroad stockholders throughout the country … perhaps something along the lines of “for every 10 shares of Penn Central, Erie Lackawanna, Central Railroad of New Jersey, Lehigh Valley, or Reading, a stockholder would receive one share of the new company.”

Since I was working as a part-time stockbroker, it was easy to find out that both Penn Central and Reading common stock were trading on the New York Stock Exchange for about $2 a share. Ditto Jersey Central, but on the NASDAQ. Erie Lackawanna common was held by Dereco, the Norfolk & Western subsidiary set up in 1968. This left only Lehigh Valley. Just where was The Route of the Black Diamond?

Thanks to some strategic positioning in years past by the PRR, Lehigh Valley wound up tucked away safely in Penn Central’s portfolio – at least 97.33 percent of it. But where was that remaining 2.67 percent of stock? This still represented thousands of shares. As a broker, I fairly easily determined that they traded infrequently on the “pink sheets,” the over-the-counter marketplace for inactive stocks. The pink sheets operated trader-to-trader via telephone, and the last trade I could trace in mid-1972 was at $1.25 a share.

OK, now I had found the market – inactive as it was. Caution thrown to the winds, I instructed the trading desk at our small firm to place an “OW” (Offer Wanted) for Lehigh Valley common in the pinks, gave them a big $1 price for the first 100 shares, and sat back, biding my time.

Sure enough, toward the end of 1972, I was at my full-time job as a towerman holding down first shift at Roseville Avenue on EL’s Morris & Essex Division when the outside phone rang. It was Harold, the trader at our firm: “Bob, you just got hit with 100 Lehigh Valley at $1. What do you want to do?”

“Drop the bid down to 50 cents,” was my quick response. Fifteen minutes later, the phone rang again. It was Harold again: “Bob, you got another 500 at 50 cents. What do you want to do?”

“Drop it down to 25 cents.” And we were off to the races. In the next two weeks of tax selling, I accumulated a total of 2,100 shares in dribs and drabs before I finally told Harold he had better stop as I began to worry that even at this price, it might be throwing money down the proverbial drain. Having lost some faith in the far-fetched scheme, I even instructed Harold to have the actual certificates sent to me on the theory that at least they would be railroad collectibles.

Time flew on as it always does, and I virtually forgot about the handful of LV stock certificates that sat in my desk drawer. As we all now know, Conrail came into being a few years later and in its formation no mention of recompense was made to common stockholders of the bankrupts. Since Lehigh Valley stock didn’t publicly trade and I was no longer a stockbroker, I didn’t bother to investigate. I mentally wrote the whole thing off.

Ten years, in fact, passed, until one day a large packet of mail arrived at my mother’s house from Penn Central, which was in the midst of its own reorganization. Penn Central was reformulating itself into a holder of insurance companies, real estate, amusement parks, and other non-railroad activities, but needed to get its financial house in order.

Leafing through the hundreds of pages in the plan of reorganization, the boilerplate seemed to stipulate a domino effect of bond after bond. If the most senior bond was paid and if there was enough money left over, the next bond (and its accrued interest) would be paid, and so on for scores of bonds and preferred stocks of forgotten subsidiaries. At the very end of the prospectus came the Lehigh Valley Railroad and there, amazingly enough, was a statement (that I reread a dozen times), saying that if all previously stated payments were successfully made, Lehigh Valley common stockholders would receive $10 a share! “Sure, and Conrail will bring back steam,” I thought.

About six months later, though, in early 1983, I was astonished to find a letter from Penn Central telling of its successful reorganization and instructing me to submit my Lehigh Valley stock, which I promptly did. A few weeks later, I received the eagerly awaited check for $21,000 – not a bad return for my $725 investment! At this point, I did some more digging as to why my shrewd investing had paid off so handsomely.

From what I can determine, it seems that Lehigh Valley had one asset Penn Central wanted very badly, and to gain this, PC needed ownership of my stock. It was the Valley’s huge losses from the 1950s right up to April 1, 1976. These tax-loss carry-forwards could be applied against Penn Central’s current profits from its new non-rail units so as to avoid paying taxes in the 1980s.

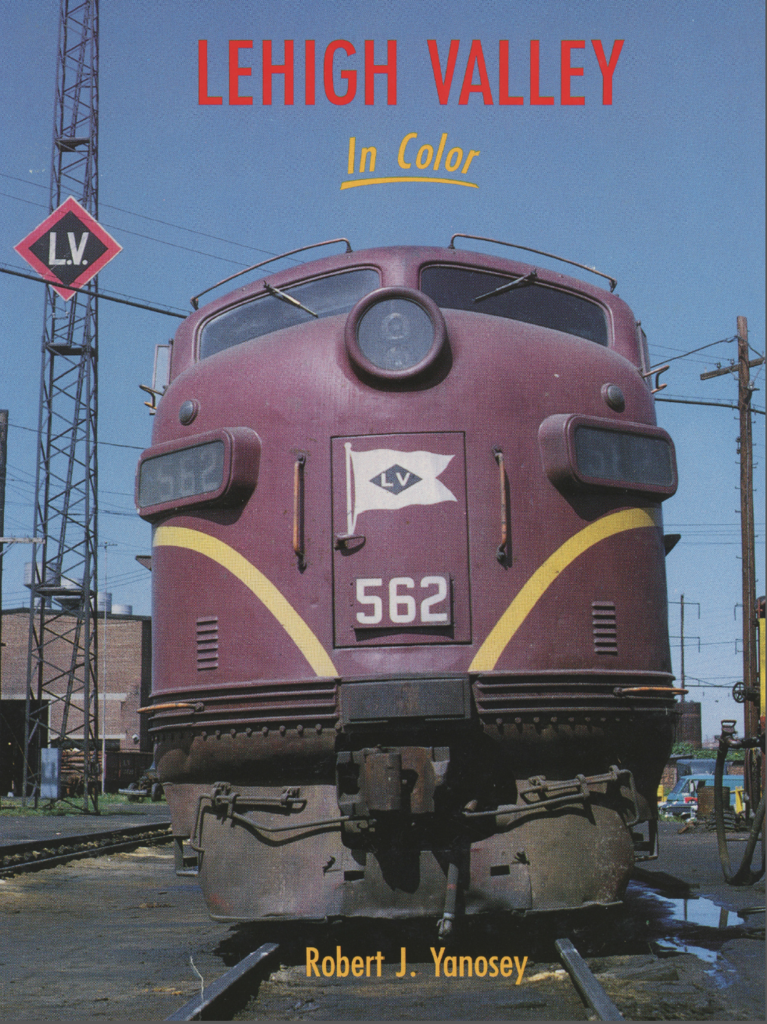

For me, the money was a windfall and helped me found Morning Sun Books, two of whose first products were books on Penn Central and the “blue-chip” Lehigh Valley.

That is so funny!

What a great story!

I often wondered about how railroads were kept ‘separate’ even though it was common knowledge LV was held by PRR, EL was a N&W/NS property and the like.

I guess it had to do with financial shenanigans promulgated by the ludicrous fed regulations strangling the entire industry for most of it’s existence.

But whatever the reason, I’m glad I got to see the colorful “competitors” rolling in and around my home town of Rochester New York in the 1960’s. LV apparently kept just enough of an alternate route that it didn’t warrant an obvious, immediate merger/elimination like DL&W and Erie did in 1959.

My hope is one day there will be serious deregulation to the degree interurban/intercity rail travel will become profitable again for the railroads. Maybe we’ll see a system tax highways and airports to death to subsidize rail improvements exactly as railroads were bled to death (literally) to subsidize their competition.

Stranger things have happened. Maybe the time is ripe to turn up the heat on those ‘powers that be.’