Lonely. Isolated. Desolate. Remote. The list of words to describe how this place — one of the (if not the) most sacred sites in American railroad history — feels is nowhere long enough.

To come here into the high desert is to be on a pilgrimage for a glimpse into the unending sagebrush, rocks, and nothingness that is Promontory Summit, Utah, the location where the first transcontinental railroad was completed.

This is a place that evokes questions into which we can only hope to get an insight. Consider this: If it feels that isolated now, imagine how Chinese and Irish construction workers felt 150 years ago when they were clearing a roadbed, laying gnarly rough-hewn ties, pounding misshapen spikes, and jockeying sticks of rail to make a way for the latest technological achievement, the iron horse. They must have felt like they had exited the map of humanity. Or fallen off the Earth. It would be the equivalent to the 1969 moon landing — putting people about as far away as you can to do an extraordinary deed, and do it well, despite adverse conditions.

Even the way the clouds move overhead in a swirling, lazy fashion, wrapping themselves around peaks and ridges, adds to the impression that this must be among the most inhospitable historic sites and tourist attractions in celebration of a major event in our national story. There are no fast-food restaurants crowding the parking lot, no hotels flashing brightly lit signs, no miniature golf or ice cream stands.

The isolation is part illusion, for just across the ridge, at the foot of the abandoned Promontory grade, is the massive plant that produced solid fuel rocket motors for the space shuttle (with an estimated total 37 million hp) — an incredible leap ahead from the state-of-the-art 1869 4-4-0 (with its estimated 540 hp).

The Golden Spike site is owned by the National Park Service

During a June 2018 visit, these thoughts and others compete for space in my head as I trudge along the dusty walking trail that was once the Central Pacific main line. Visions of workers digging cuts and hauling fill material with mules in this otherwise tranquil scene of undisturbed nature dominate my mind: This is brute strength and hard work personified.

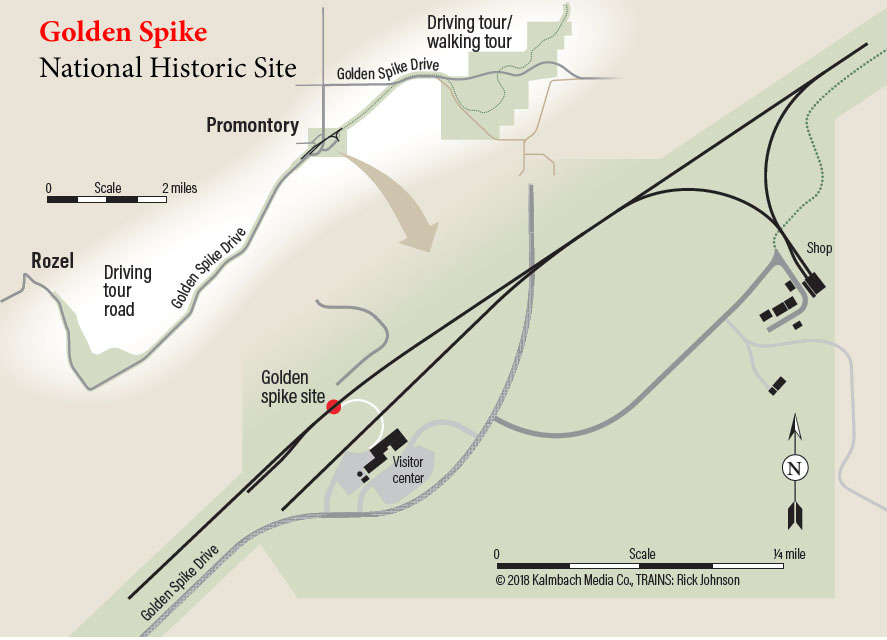

Promontory today is a gentrified National Park Service Historic Site; the official name is Golden Spike. It comes complete with a visitor center, park rangers, 4-4-0 replicas in steam, and re-enactments of the May 10, 1869, last spike ceremony. You can drive significant portions of the original right-of-way — yes, you can bounce along in your SUV at 20 mph and get a sense of what it was like in the cab of an American-type locomotive with evocative names like Antelope (the locomotive which was pulling Stanford’s train bound for Promontory when it hit a tree in the Sierra and had to be taken off), Juno, and Terrible — and you can get out and walk, reflect, and ponder “the wedding of the rails” or “east meets west” as May 10, 1869, has been commonly referred to.

It wasn’t always this way. For a few months after May 10, the two railroads interchanged here, until good sense prevailed and they moved the interchange to Ogden, with Central Pacific operating the Promontory stretch. There was even a roundhouse and a small town here for a few years. But as far as commemorating one of the biggest events in the nation’s history, there was no marker here, nothing to note the event until Central Pacific successor Southern Pacific put up a modest monument in 1919.

Indeed, in many ways, Promontory had been neglected and forgotten. SP bypassed it in 1904 with the Lucin Cutoff across the Great Salt Lake, making the route an out-of-the-way, lightly used branch for farmers and cattlemen. It was of such little consequence that SP ripped it up in two pieces, with the first part removed in 1933. The rest was sacrificed in 1942 in support of World War II (with the rails going to military bases in Utah and Nevada).

But Promontory is too important in U.S. history to ignore. The iconic Andrew J. Russell image “East and West Shaking Hands at Laying of Last Rail,” better known as the champagne photo (see pages 4-5), is one of the few railroad pictures that almost all Americans know. It has a place right up there with the photo of the Wright Brothers’ first flight, or the attack on Pearl Harbor, or the Apollo moon landing. The event itself resounds with American daring, achievement, and swagger. It demands a place to commemorate where the golden spike was driven on that spring day, in front of an estimated 1,000 spectators, workers, and railroad officials.

After 38 years of lobbying by local resident and newspaper writer Bernice Gibbs Anderson, the site became part of the National Park Service on July 30, 1965, less than four years before the Golden Spike centennial. A rock-and-wood visitors center was completed in 1969, just in time for the centennial event that attracted 28,000 participants, including appearances by the vaunted Mormon Tabernacle Choir and famous western movie actor John Wayne.

It was another 20 years after acceptance into the park service before the replicas of the two locomotives, the Central Pacific Jupiter and Union Pacific No. 119, were commissioned, and another four years before they were placed into service on May 10, 1979. That completed the site. Today, some 60,000 visitors annually trek to this place, located 35 miles west of Brigham City, Utah.

Two dazzling 4-4-0 replicas nose to nose, just like in 1869

The 2,735-acre site — which is under consideration for national park status (more on that later) — covers more than ground zero for the transcontinental railroad. It extends to the west to include the celebrated section of track where Central Pacific’s mostly Chinese workforce completed 10 miles of track in one day. It extends to the east to incorporate the Promontory Mountains grade with its parallel cuts and fills, and the spectacular Big Fill, where Central Pacific built a massive fill next to Union Pacific’s wooden bridge that was so flimsy it was only used for six weeks before the railroads agreed that the neighboring CP fill was the better way to go.

This is a sprawling site that fulfills expectations — standing in awe of two dazzling 4-4-0 replicas on display nose to nose, just the way the originals were in 1869, is what we all want to do. It also is an adventure to pose for a picture next to the “10 miles of track completed in 1 day sign” on the lonely driving tour west of Promontory or reverently walk to the Big Fill site.

One aspect of the site that engages visitors is the re-enactment of the last spike ceremony. It brings the story to life. The 20-to-30-minute presentation is given on May 10 and every summer Saturday by volunteers, park rangers, and good-humored audience members who are recruited (some say “railroaded”) to fill minor parts.

Among the cast is Richard Felt, who has been with the production since the 1969 centennial event. He was 28 years old when he started by playing the part of Harvey Wilson Harkness, who presents the ceremonial spikes to the Central Pacific’s Gov. Leland Stanford and to Union Pacific’s Dr. Thomas Durant. He is the last active member of the centennial cast, and he looks forward to the 150th event with great enthusiasm.

“The 1969 re-enactment was the 100th anniversary, and they embellished the script, and there was an older man who couldn’t memorize the new and longer script, so they got me,” Felt says. “We were also having a beard-growing contest, and I was growing one, and the part they had open called for a man in a beard.”

In the 50 years since, Felt has played every part in the presentation, which can be done with as few as seven or eight members or as many as 15. He has most recently played Stanford.

The re-enactment began in 1947 to help commemorate the centennial of the Mormon migration to Utah, and has since become a tradition at Golden Spike. In the years following the 1969 centennial, the ceremony was recreated as many as five times a day, seven days a week. A tent city was created to replica the camp followers who tagged along with construction crews. With that, the clanging of a blacksmith, the smell of biscuits baking, and the raucous piano playing and laughter in a saloon became part of the scene. After the replica steam locomotives came, the focus changed, and the tent city faded away. But not the re-enactment ceremony.

“A lot of people are interested in trains,” Felt says. “A lot of people are interested in history; and a lot of people are interested in their own history — we have a lot of Chinese people who come out to honor their ancestors, and the Mormons do, too; they did a lot of grading through Utah. We get a lot of people who point out relatives in Russell’s famous picture.”

As with so many volunteer activities that are demanding of personal time, recruiting young people to ensure the future of the re-enactment is critical. “That is a worry,” Felt says. He is hopeful the 150th anniversary will enthuse a new generation.

The big celebration of the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad

The May 10, 2019, presentation will be special, Felt says. “We considered this past May as our dress rehearsal for next year,” he says. “We practiced every Monday for two months and added some to the introduction and conclusion,” which will include an antique camera on a tripod with flash powder. It will be used to set up a recreation of Russell’s famous champagne picture before the engines are pulled together.

“We’ve cheated a little; in the end we have Stanford and Durant shaking hands. In the picture, it’s [Chief Engineer Samuel] Montague from the CP, but we don’t have a Montague in our re-enactment.”

And that brings us to 2019’s celebration and beyond.

At press time, plans were still in preparation for events on Friday, May 10, 2019, and the ensuing weekend. The re-enactment will be key, as will entertainment, locomotive demonstrations, and food vendors (normally, there is no food available at the site). Plans also were underway to have remote parking and shuttle service with an expected attendance over the weekend of as many as 50,000. For a historic site that gets only slightly more visitors than that in an entire year, it will be an overwhelming weekend, and numerous elected officials and other dignitaries are expected to attend.

But that is still ahead, and before that something significant may happen to the site. Before the big party in May 2019, U.S. Rep. Bob Bishop from Brigham City, hopes Congress will pass legislation to designate Golden Spike as a National Park, moving it up from a historic site. The designation doesn’t provide more money for the site in Box Elder County, which Bishop represents. But it does elevate its status, and should result in increases in visitation.

His legislation also creates the Transcontinental Railroad Network to place emphasis on this and other sites important to the story of the first railroad across the West. Bishop, a former high school history teacher who said his ancestors arrived by foot and by train in the late 19th century, tells Trains that also he would like to announce plans for a new, larger visitor center next May 10.

He appreciates the importance of the site: “It was estimated at the end of the Civil War that the people of the nation would degenerate into violence and conflagration. The transcontinental railroad was the catalyst that allowed our nation to rise above this. It united a divided country. It was the beginning of modern transportation in the United States. It moved us forward.”

That message is one that you’ll hear echoed if you ask park rangers on site why Promontory is important. It is not just a railroad story or a chapter in the westward expansion of the U.S., they will tell you. It is both of those things, but Promontory and the transcontinental railroad are also the physical connections for the country’s reunification after a bitter conflict, a truly epic and inspiring event that brought together the country from one shore to the other.

Promontory today is where that story is best told. Stand here on a gentle summer day and watch as families, vacationers, and adventurers from across the nation and around the world trickle in and take their seats to watch the re-enactment ceremony.

Watch their faces as they take in the shape, the beauty, and the glitz of the Jupiter and No. 119. Share with them the moment when the locomotives come together just as we’ve all seen in Russell’s photo. Take a deep breath together as a re-enactor raises the golden spike high before placing it into the replica laurel tie. That’s when the realization hits you: Railroading was made to change people’s lives for the better, and it did just that at this very spot 150 years ago. A few taps with the sledgehammers, and the telegrapher taps out a simple message: “Done!”

Interested in learning more about the history of the Transcontinental Railroad? You’ll find it in our special issue, available online.

Great article. I have about 30-odd train books. One question that has always been in back of my mind, from a child reading about this event for the first time, was: how did two trains on the same track facing each other, move on? No PR article or book I’ve ever read covered this rather important point. I see the map here, and the design obviously works, but, was it in place back then? Or did each train back up 50 miles, or, was a siding hastily built? Odd, the stuff that sticks in one’s mind. Thanks

What a wonderful Birthday/Anniversary Present that to advance the site status from Historical Site to Natio