The Leland Stanford Mansion in Sacramento, Calif., offers today’s visitors a glimpse into the life of a remarkable man — Central Pacific Railroad president, California governor, and founding father of a great university.

Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis P. Huntington, and Stanford all had mansions, but only one survives today, now as a museum home.

The Leland Stanford Mansion in Sacramento underwent several incarnations and tells a compelling story of love, loss, and legacy. If you are interested in tracing what’s left of the first Transcontinental Railroad, the opulent 44-room home offers a time-travel experience.

After 20 years of exhaustive studies and meticulous restoration, it is now open seven days a week, and admission is free. The mansion is only closed when the governor uses it as a protocol center for visiting dignitaries. It’s actually far nicer than the official governor’s residence.

Changes to Leland Stanford’s Sacramento mansion

Originally built as a much smaller residence for a Sacramento artist, Stanford purchased the Renaissance Revival home in 1861 and expanded it twice. The second expansion in 1872 took it to 19,000 square feet, and happened after a devastating flood in 1862 that saw most of Sacramento completely inundated. The entire old city had to be raised up on jackscrews and lifted up a full story. The Leland Stanford Mansion also rose to greater heights, both to protect it from future flooding and to reflect the wealth of a railroad baron with a growing empire.

The stately home celebrates Stanford’s crowning achievement, the successful completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

Amazingly, the historic integrity of the mansion survived another major change in 1900, when Stanford’s widow Jane donated it for use as an orphanage run by the Catholic Church. (Stanford had died in 1893.) It remained a home for children in need until 1986. The current restoration preserves a remnant of that incarnation, but takes most of the house back to 1872, after Stanford’s grand post-flood remodel.

Love and loss for a Transcontinental Railroad tycoon

The Stanfords yearned to have children themselves. Nineteen years of a childless marriage created heartbreak for a couple who had everything in terms of worldly goods but whose deepest desire was to have a family of their own. When Jane, then 39, finally gave birth to a son in 1868, he was considered their miracle baby. They lavished him with love, education, and an idyllic life, including a grand tour of Europe and the Middle East, so popular among people of their class in the Victorian age.

The family also enjoyed experiments in photography and raised champion horses, though it was the travel that made the biggest mark on their lives. But in Florence, Italy, in 1884, 15-year-old Leland Stanford Jr. died of typhoid fever, leaving his father and mother distraught — and childless — once again. They later founded Leland Stanford Jr. University “for the children of California,” turning the love and loss of their only child into a legacy that endures in one of America’s top universities.

Over the years, the home at 8th and N Streets would remain a sentimental favorite for the Stanfords, since it was the birthplace of their son and their residence at the time of Stanford’s greatest business triumph, the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad. Although they had other, larger estates, (including a farm in Palo Alto, Calif., and a 60,000-square-foot mansion on San Francisco’s Nob Hill), the Sacramento mansion was the scene of their best years.

Restoring Stanford’s mansion

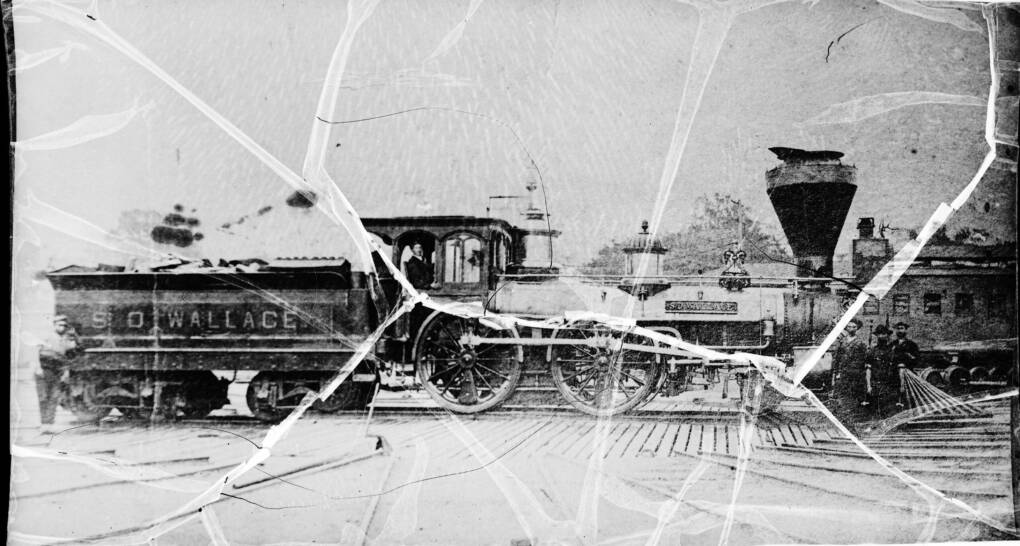

Stanford celebrated his status as rail baron with a bit of memorable interior decoration that inspires visitors to this day. The entire house transports the visitor back in time to the era when the Transcontinental Railroad was built, but the dining room contains the most whimsical celebration of that epoch. Here the railroad enthusiast can revel in the gas-fueled sconces that feature etched-glass globes depicting 1870s balloon-stack locomotives. Additionally, a tall china cabinet is adorned with a custom cartouche emblazoned with a steam locomotive carving.

The dining room table (which can expand with its mate to seat nearly 70 people) has ornate, turned legs that evoke miniature steam engines. And the most impressive railroad-themed item of all is a massive sideboard that resembles the front of a period locomotive, complete with stack, boiler, classification lights, and pilot (cowcatcher) motif. Guests in this dining room would never forget where the Stanford fortune had come from.

Survival of original furnishings in historic homes is rare, let alone in a home that operated as an orphanage for nearly a century. But when the state of California acquired the home from the Sisters of Social Services, they had a lot to work with as they undertook a $22 million restoration.

We have the religious sisters to thank for much of the mansion’s authenticity. During the orphanage days, much of the original Stanford family Victorian furniture was stored in the massive attic space created by the home’s mansard roof. This roof is a character-defining feature of the mansion, and served as the perfect storage place for a treasure trove from an important chapter of state history.

Nearly half of what you see in the mansion today originally belonged to Leland and Jane Stanford.

The restorers also had an extensive photographic record to help them recreate the décor that had been lost. Stanford had commissioned Alfred A. Hart to photograph the inside and outside of his home in 1868. Hart is legendary for the photos he took during the Central Pacific construction period; most of the photos from the early CP are his. Also, in 1872, following the second expansion, the home was photographed again by Eadweard Muybridge, the noted photographer who became famous for taking pictures of Stanford’s horses in motion. (The project was undertaken to settle a bet — did all four of a running horse’s hooves leave the ground at the same time – and Muybridge’s series of stills amounted to the first motion picture in history.) Muybridge’s detailed photos of the Sacramento mansion’s interior were invaluable to the restoration: They enabled California State Parks staff to meticulously reconstruct every detail, room by room, right down to the carpet patterns.

The Leland Stanford Mansion serves as a strong link to the glory days of California’s Gold Rush pioneers.

Want to find out more about the Transcontinental Railroad?

Facts, figures, history, and more are available from our special Journey to Promontory magazine, available at our partner shop, the Kalmbach Hobby Store.

wow, that sounds like a great place to visit. Was in Sacramento years ago on our first trip to CA, stayed with Mom’s niece who lived there. We did leave for a few days to travel to San Fran and L.A. but bulk of time was spent in the capitol. Dad drove their car around as my cousin did not know how at the time and she showed us many interesting places like Capitol and Sutters Fort. This house would have been an orphanage in those days and no railroad museum like today. Hope to get back there some day as I do still have cousins living there.