Transcontinental Railroad financial troubles

After just 18 years of operation, there had been so many irregularities and so much concern over the Union Pacific’s ability to repay its federal loans that in 1887 Congress created the United States Pacific Railroad Commission to investigate the finances and structure of all the major railroads initially described as “the Pacific Railroad” project.

Fast-and-loose financing challenges

Over months, the commission held hearings, took depositions and testimony, traveled over the railroads in question, and tried to reconstruct the financial records of the entire Transcontinental Railroad project. The chairman said the commission’s work was made more tedious by the fact that “the construction companies or inside combinations that built five of the six roads have destroyed or concealed their books.”

At the conclusion of the probe, the chairman, Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Pattison summed his feelings this way: “The public interest has been subordinated by these companies to the stockholding interest upon the claim that the stockholders owned the railroads and could manage their own business in their own way. Nearly every obligation, which these corporations assumed under the laws of the United States, or as common carriers, has been violated. Their management has been a national disgrace.”

The commission submitted its official report to President Grover Cleveland in 1888. It estimated that the cash profit to the officers and directors of Union Pacific Railroad and Credit Mobilier, a special company used to syphon money from building the first Transcontinental Railroad, as a result of the construction fraud alone was $23.3 million. Conservatively, the amount stolen was just shy of $1.17 billion in today’s dollars, or about $1.25 million for each of the railroad’s 1,038 route-miles from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to just west of Ogden, Utah.

And that was just the construction phase. It’s little wonder that the U.S. government grew increasingly annoyed with UP as fraud and corruption chugged along for another 10 years.

E.H. Harriman saves Union Pacific

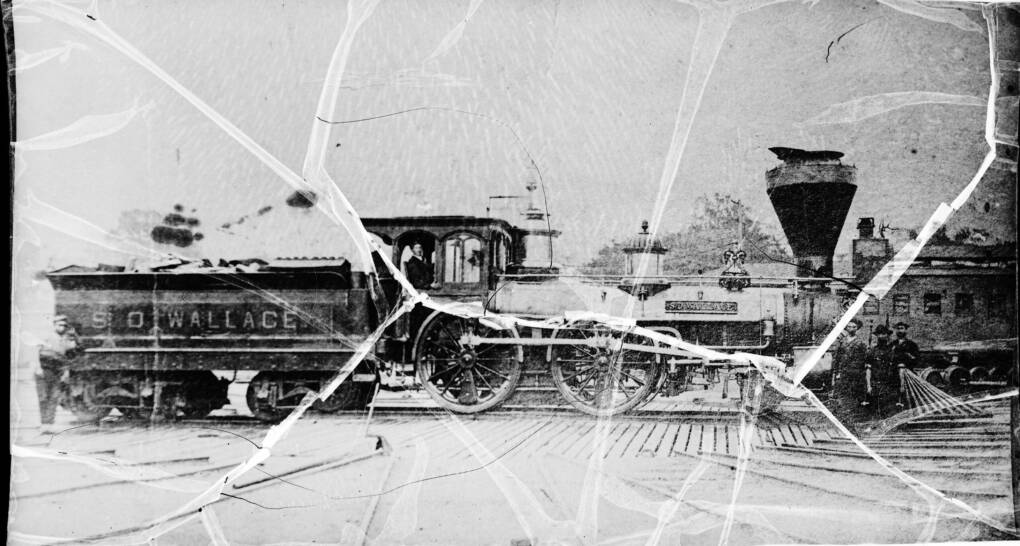

The Union Pacific we know today dates from 1897, when it was reorganized for the second time. From that point, UP was free from lingering restrictions dating back to the Transcontinental Railroad project.

The railroad’s final manifestation came under the leadership of E.H. Harriman, one of the railroad industry’s most successful executives. Harriman had a vision: a UP with a first-rate physical plant competing in markets throughout the West and taking full advantage of its location, strategic opportunities, and the booming traffic of the early 20th century. All it required was leadership, close attention to detail, and lots of cash. Harriman supplied all three.

Of course, a full accounting of the UP’s 150 years is more complex.

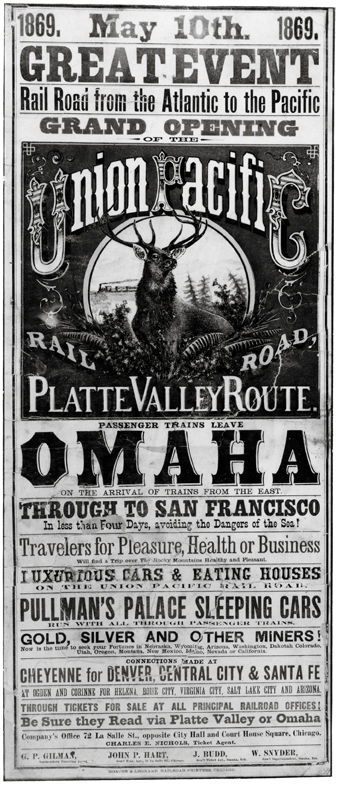

Originally, the UP – and by extension, the Transcontinental Railroad, was a collective expression of national will and resolve. Like the equitable distribution of land and access to higher education, its objectives — to physically unite a continent struggling to become one nation — were rooted in sincere patriotism and a belief that the nation was a unique and successful experiment in self-determination.

The American Civil War and its aftermath subverted the ideals of the laws authorizing the Transcontinental Railroad. Despite the best intentions of the laws’ framers, it took only a few years for corporate crooks and post-Civil War opportunists to turn the UP into a perverse kind of business-school case study: a visionary project launched with high expectations, then cynically manipulated to benefit a few people. That was a common outcome during the late 19th century. And it set the stage for the Progressive Era, which restored some notion of fair play and ethical business practices.

That trajectory is less about the UP and more about the U.S. in which it developed. At almost every step, the UP was a reflection of the society that created it and that it served. It is a testament to the original purpose of the Transcontinental Railroad that it has continually reinvented itself as the future required. In its third act, UP not only survived, it prospered. It became North America’s largest railroad, and one of its most respected.

UP’s sesquicentennial began July 1, 2012, on the 150th anniversary of the Pacific Railroad Act. It will wind down in 2019.

Seven years is a long time to celebrate a railroad’s anniversary. But this is no ordinary railroad and no ordinary anniversary. The story we continue to tell about the Transcontinental Railroad sounds familiar. But beneath the clichés and glossy yellow surface is much more.

Interested in learning more about the history of the Transcontinental Railroad? You’ll find it in our special issue, available online.