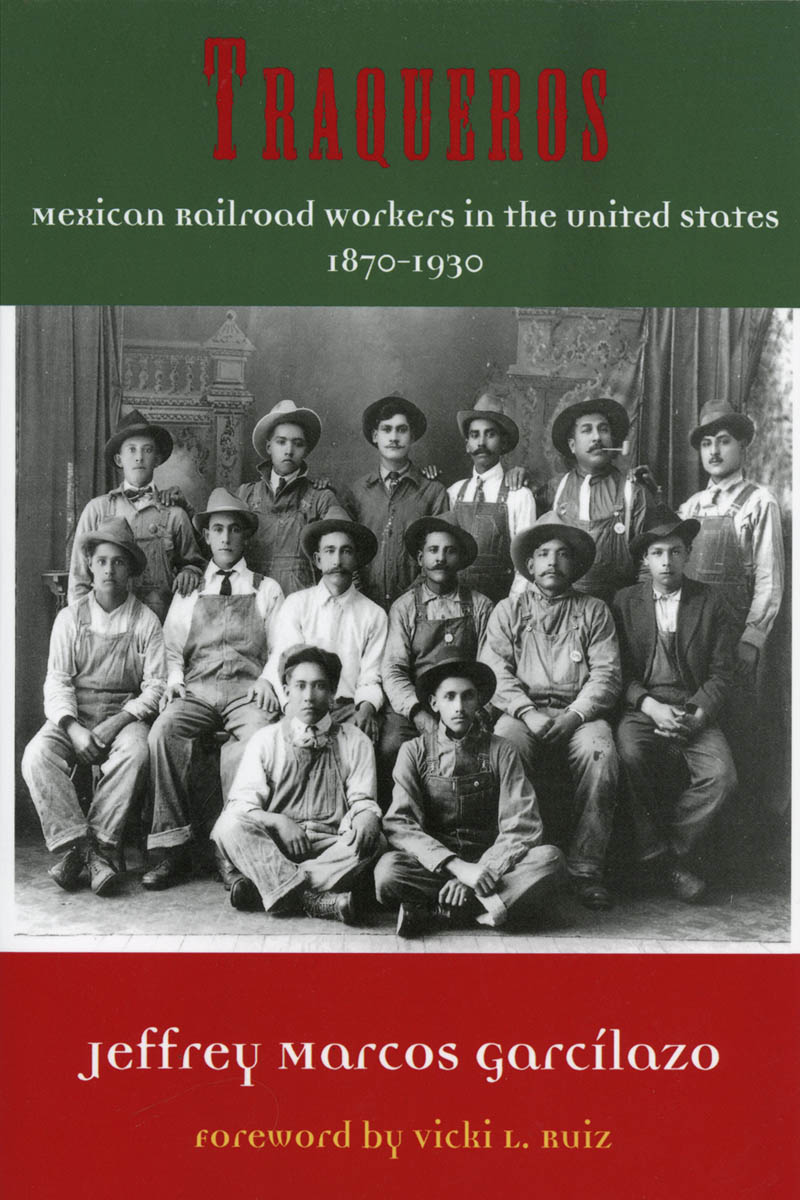

No. 6 in Al Filo: Mexican American Studies Series

By Jeffrey Marcos Garcílazo, Ph.D.

Forward by Vicki L. Ruiz, Ph.D.

University of North Texas Press, 1155 Union Circle, Denton, Texas, 76203-5017; 256 pages, map, tables, illustration, footnotes, index, bibliography, paperbound, 6 x 9 inches; $24.95. untpress.unt.edu

Jeffrey Marcos Garcílazo sets out to dispel the “popular lore” that Chinese and Irish laborers alone built the railroads of the West. His mining of archives and other sources results in what a colleague calls the first comprehensive study of Mexican track workers and their unrecognized role in building and maintaining U.S. railroads.

“During the late 1800s, virtually all types of native-born and immigrant labor worked on the tracks in this region at one time or another,” Garcílazo writes in Traqueros. “However, by the turn of the century, Mexican immigrant labor far outnumbered all other groups of immigrant and or native-born labor on the tracks in the Southwest.”

Garcílazo finds the immigrants overcoming low wages, exploitive commissaries, poor living conditions and ethnic prejudices to create a distinctive railroad-worker culture. Even women and children joined their husbands and fathers as railroads sought ways to increase worker loyalty. One chapter is dedicated to the resulting boxcar communities, permanent and mobile apartments and dormitories dotting sidings and yards across the Southwest, Midwest and as far east as Pittsburgh.

The track workers called themselves traqueros (trah-CARE-oes) derived from “track” much as roofing crews in the Southwest today are known as rooferos. Other chapters detail railroads’ place in socioeconomic development, the work experience and labor struggles.

Garcílazo traces the first hiring of native Latinos to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway pushing west into what had been Mexico and previously Spain before the U.S. invasion and conquest of the late 1840s. The influx of immigrant labor surged after 1881 when the Santa Fe and the Southern Pacific reached the border at El Paso, Texas, which the author calls the Ellis Island of the Southwest.

Adding to the northward flow were political turmoil in Mexico, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which ended immigration of Chinese labor, and the railroads’ affinity for laborers they could pay less than Anglo workers.

The railroads also skirted a federal ban on employers recruiting foreign labor by using third-party contractors to provide workers from Mexico. The Santa Fe went so far as to provide stationary and stamps for its workers to write home to encourage friends and family to migrate northward.

A 1928 study by the Santa Fe revealed Mexican track workers on its Kansas City Division grew from less the 7 percent of the workforce in 1905 to more than 91 percent in 1927. Mexican workers dominated seasonal extra gangs on the Rock Island, according to one report.

Garcílazo’s story ends as traquero numbers begin dropping due in part to 1-2 million deportations of both immigrants and citizens under President Herbert Hoover’s politically motivated Mexican Repatriation Campaign.

This book stems Garcílazo’s 1995 doctoral thesis with its academic style reflecting deep research into primary and secondary sources. Oral histories of traqueros and their families add the human component to the boxcar lifestyle and living in the industrial shadows. Anglo observers and railroaders and officials, often reflecting the prejudices of their times, flavor the story as well.

Garcílazo’s work qualifies as ethnic studies, a topic out of favor in some political circles and essentially banned from public schools in Arizona where a court challenge is in its sixth year. Still, if it’s true history is written by the conquerors, Traqueros provides a valuable perspective on Southwestern history in general and railroad history in particular.

While extensively footnoted with a lengthy bibliography, the only photo of traqueros is the group portrait on the cover. A single map of Western and Mexican railroads is more illustration than resource, and two 1911 Santa Fe schematics sketch trackside section housing workers could build for themselves from scrap materials.

Garcílazo, once a United Farm Workers organizer, grew up in the railroad city of Colton, Calif. He was an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, when he died in 2001 at age 44 of complications from routine surgery. At the time he was revising his thesis for publication, a project completed and published in 2012 with support from his parents.

Thank you for publishing this book. The contributions and sacrifices of Mexican immigrants to this country are largely overlooked. I intend to purchase a copy for my mother as well as myself. My maternal great-grandfather worked for the Rock Island railroad from 1918 till his death in the 1950’s. My maternal grandmother was born in a railroad car in 1928 in Van Horn, Texas; her older brother and younger sisters were also born in rail cars. Interestingly the 1930 & 1940 US Census records them leaving in a railroad car.