Where do TGVs come from? To find out, you have to board a train in Paris (a TGV, naturally) and head to the city of La Rochelle on the western Atlantic coast, where the train-builder Alstom has been turning out high speed trains for almost 30 years. Alstom has sold more high speed trains than any other European manufacturer.

Since production began in the late 1970s, Alstom has produced 647 TGV-style trainsets in nine different varieties-539 alone for SNCF (French National Railways) and its Thalys operation (Paris-Amsterdam and Cologne-Amsterdam routes), plus 38 TGV-derived Eurostar trains, 46 KTX trains for South Korea, and 24 AVE trains for Spain.

The 293-mile journey takes 2 hours 58 minutes, using the 187.5-mph Atlantique high speed line from the Paris suburbs to Tours (138 miles away), and then the conventional tracks of the French rail network where speeds are held to a “slower” 125 mph.

Alstom has been building TGV trainsets at La Rochelle since 1978, but the factory there has been building trains since World War I when it was set up by the U.S. Army and Standard Steel Co. to assemble rolling stock to transport men and equipment. In April 1919, Middletown Car Co. took over the plant to build rolling stock for the French government, expanding the facility. Pullman Car Co. became the next owner, selling it to the Rothschild banking family in 1946. Ten years later, it was taken over by the railway builder Brissonneau et Lotz, which later became part of Alstom.

What is high speed?

Eric Avril, Alstom’s manager responsible for product strategy for Very High speed trains, explains how Alstom defines its market: fast trains from 137.5 mph (220 kph) to 187.5 mph (300 kph) are “High Speed,” while trains above 187.5 mph are “Very High Speed” (VHS). Alstom’s newest TGV Duplex trainsets for SNCF, plus the new AGV train for Italian company NTV, are in the VHS group, as are other Alstom projects proposed or under development for China, Brazil, Morocco, the Arab Gulf States, and the United States. Avril himself worked on the introduction of Amtrak’s Acela trains (built by a consortium that included Alstom and Bombardier), spending a year living in New York.

Avril says that Europe will likely see its current 3,000 miles of high speed lines treble to nearer 9,000 miles within a decade or so, and roughly half this increase is already under construction! Alstom reckons the world market for high speed trains alone was worth 3.3 billion Euros ($4.4 billion) from 2003 -2007 with a 49/51 split between high speed and very high speed.

Many factors motivate countries to adopt high speed rail systems, Avril says. Not only can it transport large numbers of people quickly and safely, he adds that high speed rail lines need much less space than new roads: a double-track high speed line is 50 feet wide, whereas a new highway requires 100 feet or more. Plus, a TGV causes 20 times less pollution than a car, and 30 times less than an airplane, French railway president Guillaume Pepy remarked in a 2007 speech.

Avril says the latest travel figures show that if a journey can be made in 3 hours or less by rail, then rail will gain most of the passengers – and given the long delays at airports these days, many people regard 4 hours as the new threshold for switching from plane to train.

This mass exodus away from planes and onto trains first appeared in France between Paris and Lyon – the first TGV route to open – and it has been repeated wherever high speed rail has been introduced. With Eurostar trains sailing through the Channel Tunnel for more than 15 years, there are now few flights between London and Paris or Brussels. The same phenomenon is happening in Spain and in China, two countries that are furiously building new high speed rail lines.

Three hours can cover a huge distance at 200 mph, so Paris-Marseilles (469 miles in 3 hours) or Paris-Amsterdam (342 miles in 3 hours 19 minutes) or Paris-Cologne (339 miles in 3 hours 14 minutes) suddenly become possibilities in travelers’ minds, and a new rail corridor emerges. These latter two international routes use TGV trainsets equipped to run in four countries using up to four traction voltages for high speed and conventional lines and each country’s signaling system.

Avril says the fastest trains could soon be going 250 mph (Alstom recently introduced a 250-mph train for sale around the world), bringing 1,000-mile journeys into a 4- to 5-hour window. Imagine racing from New York to Chicago by rail in half a workday!

In preparation for breaking the world speed record in 2007 with a modified TGV, Alstom ran more than 1,200 miles of tests above 312 mph (500 kph). Avril says that every previous high speed record has led to higher-speed passenger operation so revenue speeds at 250 mph (400 kph) are entirely likely in the future, although he cautions that energy consumption rises with speed, so operators may choose to run slightly slower for that reason. Since fall 2009, Chinese Railways has been operating the world’s fastest commercial trains, which reach a top speed of 219 mph (350 kph).

Building the trains

At La Rochelle, Alstom is building double-deck TGV Duplex cars for SNCF. (The power cars are made on the other side of the country at Alstom’s locomotive factory in Belfort.) It is also building the first AGV trains for new Italian operator NTV (for Nuovo Trasporto Viaggiatori).

The only TGV type currently in production is the bilevel TGV Duplex (double-deck TGVs first entered service in 1996). Since 2009, Alstom has been building 68 Duplex Dasye trainsets with asynchronous motors that boost locomotive power 7 percent. Alstom will build 55 TGV trainsets beginning in 2010 designated RGV2N2 (double-deck, high speed, 2nd generation), with a top speed of 200 mph and equipped with multi-voltage power systems and signalling for operation to Germany and Switzerland, as well as France.

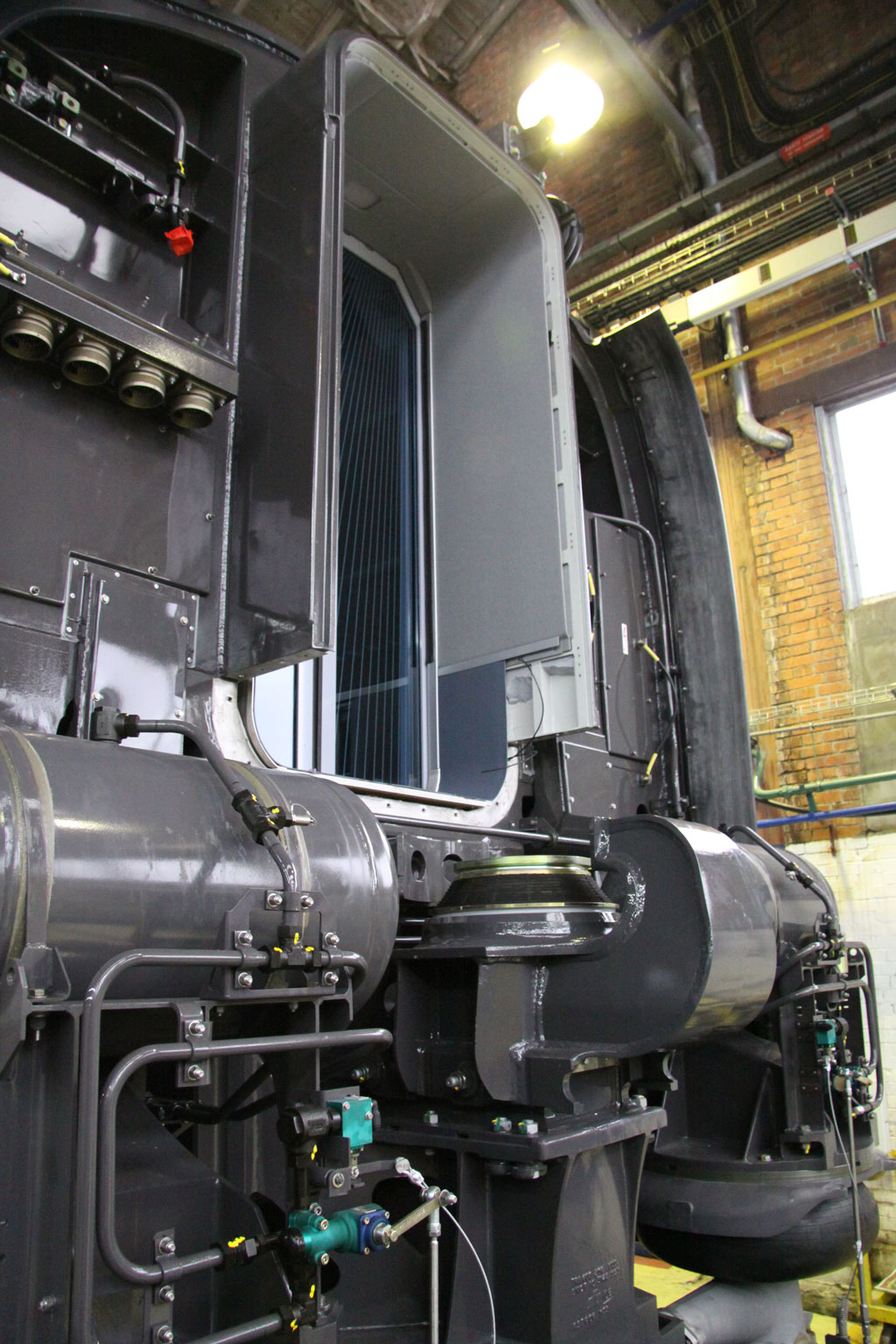

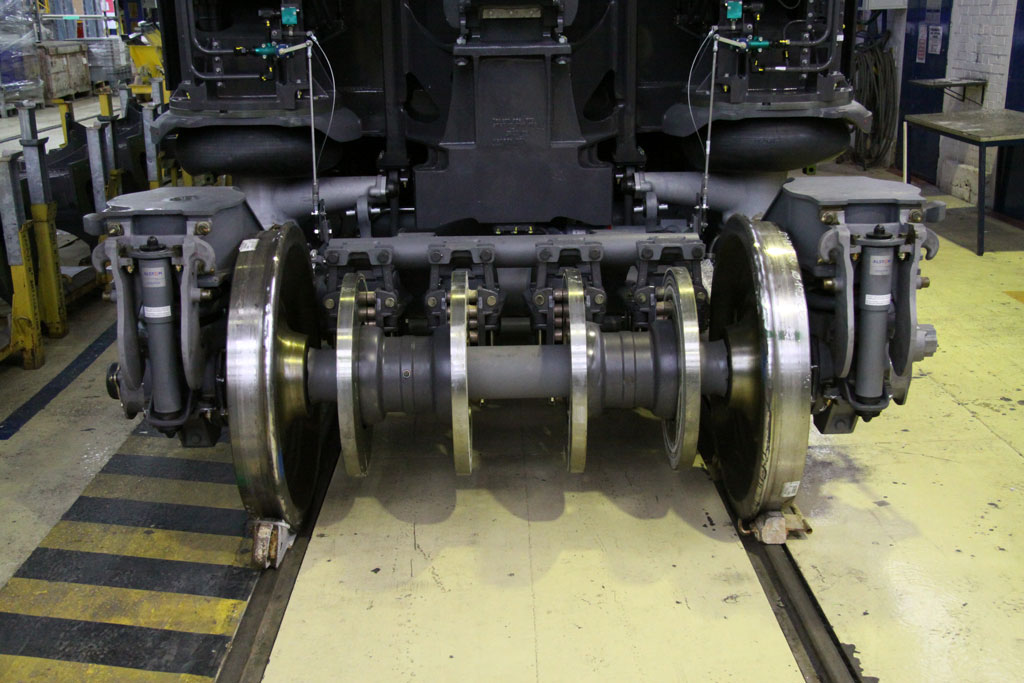

TGV Duplex coaches take around 3 weeks to build and finish. A complete 8-car set takes around 6 weeks. (Each Duplex trainset measures 655 feet, with seats for 550 passengers and a top speed of 200 mph.) Seeing the cars under construction individually lets you observe the massive disc brake systems: four discs per axle, needed to stop a train doing 200 mph. Each car shares a truck with the adjacent car, requiring only 12 trucks per trainset rather than 16 if every car had a truck on either end, saving weight, construction, and maintenance costs. The articulated design creates a semi-rigid link between the cars.

Alstom rolled out its new, 225-mph AGV high speed train in 2008, which the builder says will use 30 percent less energy than a comparable TGV. (AGV stands for Automotrice a Grande Vitesse, or “high speed self-powered unit.”) This train does away with locomotives, operating instead as a classic electric multiple unit with powered axles beneath the train (this approach was used by Japan’s Shinkansen trains from the beginning, and is also used by Germany’s third-generation ICE trains). AGV will introduce new technology, too, in the form of high speed trucks with permanent magnet traction motors, reducing motor weight and size. Alstom has an order for 25 AGV trains for Italian private operator NTV (part owned by the French National Railways), which will launch high speed service in Italy in 2011, competing with government-owned operator Trenitalia.

The AGVs are just beginning to be assembled, still in raw aluminium but destined to be finished in a smart red livery. Someone at SNCF had the foresight to trademark the name TGV – they were paying for most of the development work, after all – but Alstom made sure it owns the new AGV brand, now that the train builders, rather than railway companies, pay the development costs!

SNCF, meanwhile, plans to order a new fleet of 35 international high speed trains (with options for another 65) to be used primarily on cross-border routes from 2015 on. These services offer higher-margin growth potential – in many cases expanding rail’s market share, just as TGV-derived trainsets did for Eurostar’s Channel Tunnel franchise and the Thalys service linking Amsterdam with France and Germany (SNCF is a leading shareholder in both international ventures).

Surprisingly, the plant also builds Alstom’s slowest rail products: tram cars for France and North Africa filling one of the production halls!

KEITH FENDER is a freelance rail transport journalist based in London who specializes in European railways for several leading Britain-based publishers.