When people think about building a model train layout on a hollow core door, they most often envision an N scale layout, like our Red Oak project (which was published starting in MR’s January 2015 issue). Admittedly, hollow core doors are a convenient size for small N scale layouts, since nested 9.5” and 11” radius turnback curves fit nicely inside a 30” width. But hollow core doors come in a wide range of widths useful for other scales, as well. So I decided to see what sizes were available and sketch plans for two HO scale modules on a hollow core door.

I have to admit that my plans for my HO scale Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern were too ambitious for one modeler to build and operate alone. The layout operates well, but it’s lingered in a half-finished state for years. A couple of plumbing accidents that soaked different parts of the layout didn’t help my motivation. I need to scale back my plans and come up with something I could build and run by myself. Ideally, it should be portable, since a move to a condominium is likely in my future.

Since the pandemic, I’ve been working several days a week from a home office one room over from the old layout. My desk faces a long, blank finished basement wall that I’ve often thought could be the home of a shelf layout. But it was only recently the solution came to my mind: a bifold door. I couldn’t cut a hollow core door into two narrow shelves and expect it to support a layout. But a bifold door already comes in halves. What I’ve sketched up here is the start of a shelf-based take two on my CL&N.

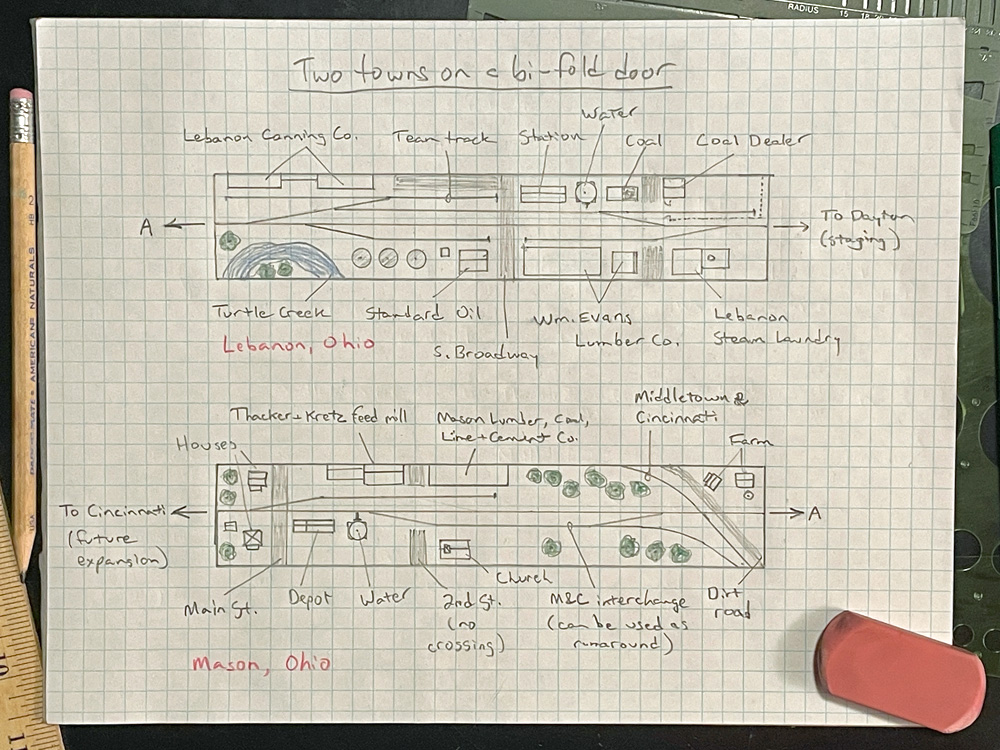

First, I checked the website of my local home improvement store to see what sizes of hollow-core doors were available. I found 80” tall bifold doors available at 24”, 30”, and 36” wide, which would translate to two shelves of 12”, 15”, or 18” depth. I drafted my first sketch on 12” shelves, but found that didn’t leave me enough depth for structures if I wanted four parallel tracks. I started over with 15” deep shelves and was much happier with the results.

The first shelf would be home to the town of Lebanon, Ohio, the northernmost terminus of my 26-mile-long prototype. I model 1906, shortly after the Pennsylvania RR bought and standard-gauged the originally narrow-gauge railroad. I knew that even Lebanon’s modest yard would require selective compression on a 15 x 80-inch shelf. In order to keep my track plan as realistic as possible, I turned for inspiration to the Library of Congress’ online archive of Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. These maps, originally compiled to document insured buildings and their construction, are great resources for model railroaders. Not only do they depict railroad track arrangements in towns across America in different historical periods, but they also show the size, shape, placement, names, and construction materials of structures in those towns.

I found a map of Lebanon in 1907 that showed the part of town I wanted to model. In addition to slimming the yard by one track, I took a few other liberties. Most of the yard and industries were to the west of the CL&N station, which I wanted to be front and center. I combined two streets (Broadway and Sycamore) into one, converted one spur into a switchback, and started placing industries.

I liked the idea of the small coal yard east of the station. Most of the freight coming to the CL&N from the north in my time period was coal, so I wanted a place to drop it off. Besides, nothing says turn-of-the-last-century small-town America like a neighborhood coal dealer. To its west I placed the railroad’s coal dock, water tank, and station.

The prototype had a house track that ran along South Street behind the depot. I didn’t have the space for that, so I put a team track on the switchback across Broadway from the station. That meant I had to lose the L. Simonton Grain Elevator, but a team track would give me many more options for shipping and receiving freight.

Warren County, Ohio, was farm country, and the CL&N was spotted with numerous small produce canneries. I put the Lebanon Canning Co on the other side of the switchback. This industry was actually just west of town, but since I had already scrapped the grain elevator, I needed this industry to represent the town’s agrarian background. Besides, I didn’t feel I had the real estate to adequately represent the industry that actually occupied that spur, the Lebanon Gas Works, with its towering gasometer.

The industries on the aisle side of the shelf would be easier choices. Standard Oil Co. would give me the chance to run a different kind of train car, and the Wm. Evans Lumber Yard was a large, busy industry of a type ubiquitous in small-town America in the early 20th century.

To fill in the right front corner of this module, I found on the Sanborn map the Lebanon Steam Laundry, an interesting-sounding non-rail-served business that was across the street from the lumber yard. On the left, I thought I’d include a loop of Turtle Creek, which ran on the south side of the town. I’ll have to laminate a layer of extruded-foam insulation board on top of the hollow-core doors to allow this below-grade scenery.

Now on to the second shelf module, which would represent some of the quiet countryside south of Lebanon. I had two items to include on this shelf: the small town of Mason, Ohio, and the interchange with the Middletown & Cincinnati north of there.

The M&C was, like the CL&N, a small railroad with big ambitions. It stretched from Middletown, Ohio, north of Cincinnati, to a junction with the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis near the Little Miami River. The Pennsy also bought the M&C and merged it into the CL&N, making the short line an important source of traffic. Middletown was home to a steel rolling mill, a large tobacco warehouse, a farm implement manufacturer, a bicycle factory, and a couple of paper mills, among other interesting industries. So this important interchange could provide a large variety of freight traffic to my HO scale railroad. A narrow shelf doesn’t give me enough room for a working interchange, so I put the interchange track toward the front of the shelf, allowing cars to be changed out by hand (“fiddled”) during an operating session. Putting a turnout at both ends of the interchange also allows it to be used as a runaround when empty.

Mason was quite a small town in my time period, even compared to Lebanon. According to a 1911 Sanborn map, the town had just two spurs serving three lineside industries — the Mason Canning Co.; the Mason Lumber, Coal, Lime & Cement Co.; and Thacker & Kretz Feed Mill. Since I already had a cannery in Lebanon, I decided to model the single spur that served both the feed mill and the lumber, coal, lime, and cement company. Between those two industries, I should have plenty of different types of cars to pick up and drop off. A few houses, a church, and the depot complete this bucolic scene.

Though I doubt you’ll want to emulate me in building a southeast Ohio short line in 1906, I hope my example gives you some ideas of how you can build your own HO scale modules on a hollow core door. It’s all about selective compression and selecting your industries to maximize operating value.

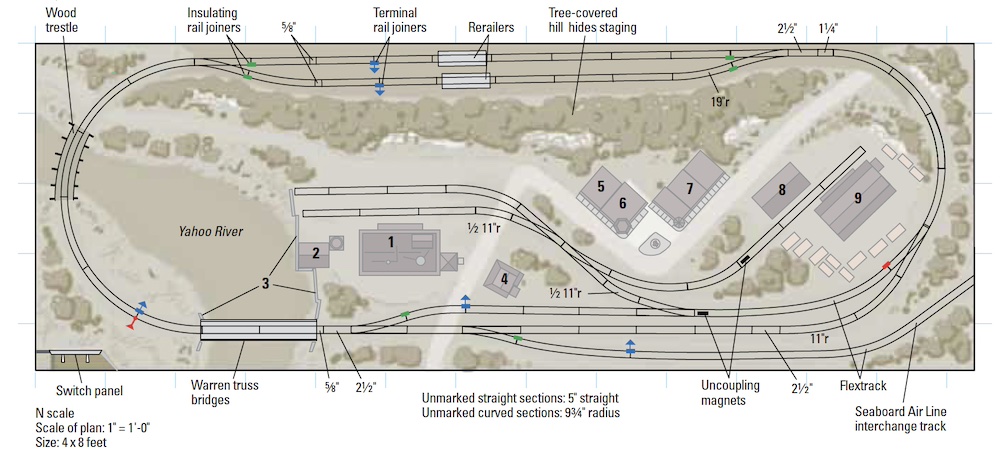

Your sketches are giving me some ideas for my staging yards. Keep up the good work.