Buffalo Central Terminal

The recent reopening of Detroit’s Michigan Central Terminal rekindled thoughts about another neglected terminal, this one resides in Buffalo, N.Y. What turn of events would need to take place to revive Buffalo’s Central Terminal? There may be significant roadblocks, but could they be overcome?

Blast from the past

First, some background. As a boy, I was captivated by Walter L. Greene’s memorable painting, “Eastward-Westward,” depicting the two 20th Century Limited trains side by side, about to depart it would seem, at a busy Buffalo Central Terminal (BCT) set against a cloudy sky. The station was brand new in the painting. Its brightly lit platforms seemed warm and inviting. The structure seemed more than a building; it represented American railroading at its zenith — powerful, permanent, and indestructible. I’ve held a keen interest in the terminal ever since.

In my youth riding New York Central’s New England States, I used to try to be awake to catch a glimpse of this intriguing colossus but always seemed to miss it. As I grew older, I’d ask a porter to awaken me. I recall the first time I saw it, on a cold starlit night from the vestibule of a NYC sleeper as we approached from the west and slowly entered the platform area.

Looming from the dead of night, almost as in Greene’s painting, the massive 270-foot high, 15-story tower stood dark and impressive — a secular cathedral. In contrast, the station platform teeming with passengers anxious to board had an attitude of urgency and anticipation of a journey in the offing. Even at 2 a.m., the station seemed busy. Carmen inspected equipment, engines were re-fueled, and redcaps and porters helped passengers with luggage. I suppose the scene was repeated each day and night with hundreds of thousands already having passed through its doors over the decades. If Buffalo had a center of activity, I thought, this must be it. Little did I realize the station was already deep into decline.

In better times

Buffalo Central Terminal was one of several Art Deco masterpieces designed by Alfred Fellheimer and Steward Wagner. It cost sole owner New York Central $14 million to construct in 1929. The Pennsylvania Railroad, Michigan Central, and Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo were minor tenants. Even though a downtown station already existed at Exchange Street, much of the reasoning for a new facility came as the result of grade crossing problems, not to mention intense competition between railroads.

Numerous committees and commissions were formed to address the problems but to little avail. Meanwhile, Buffalo was growing and expanding, and a new station would be needed to meet the future transportation requirements of the city.

With a vision of an expanding city in mind, the site chosen for the new terminal was on the city’s east side in East Buffalo where property values were relatively less expensive than that of the downtown area. The complex was built on 70 acres, of which 30 were reserved for the station and support facilities. While the railroad owned part of the property, the company found itself having to buy and remove approximately 150 homes in a poor section of town — a deal that the local constabulary welcomed.

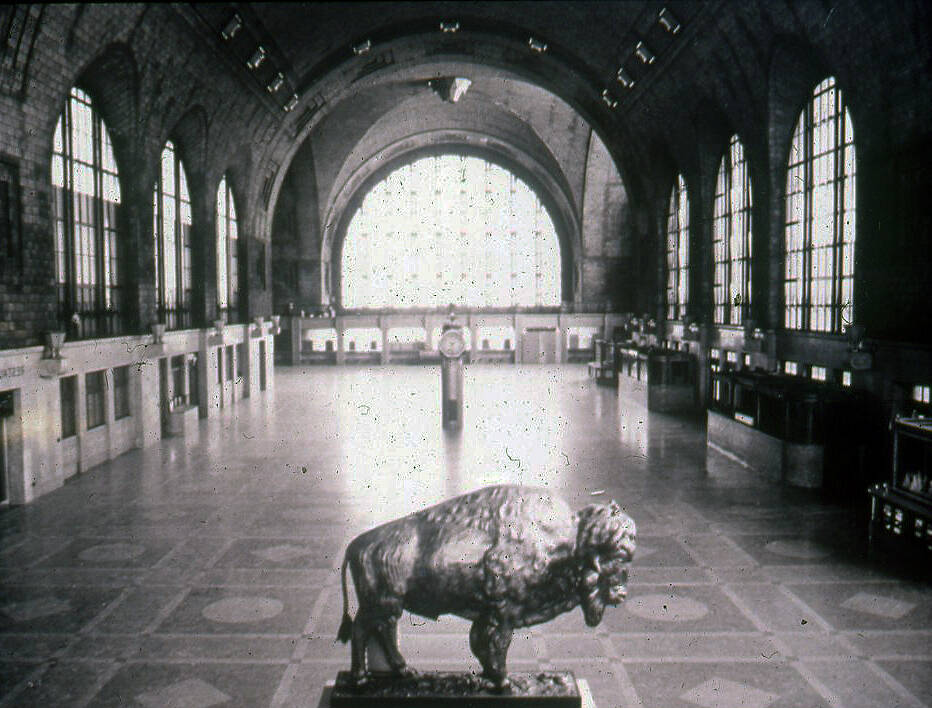

Inside, upon entering the terminal, passengers were dwarfed by the grand hall housing stores, newsstands, 18 ticket windows, and, at one end, a 225-foot long, 66-foot-wide concourse over the tracks. Its ceiling stretched 58½ feet high, dwarfing the visitor. The structure contained marble terrazzo flooring laid in geometric patterns, marble ticket counters, and a hand-laid brick ceiling in the Guastavino style — a sound-absorbing porous clay tile.

Its seven, 22-foot-wide platforms, ranging in length from 850 to 1,200 feet, served the station’s 14 passenger tracks, constructed in such a manner as to obviate the use of step boxes while still allowing the inspection of cars. Passengers reached these platforms — covered by round-end canopies featuring precast concrete roofs — by ramps instead of stairs, a design feature subsequently repeated in the designs of the terminals in Cincinnati and Toledo.

This grand edifice opened June 1929 on the threshold of the Great Depression amid a huge celebration and banquet, despite the top floors still being unfinished. Nobody knew at the time that the facility, designed to handle more than 400 trains a day, would never reach its full potential.

Kismet

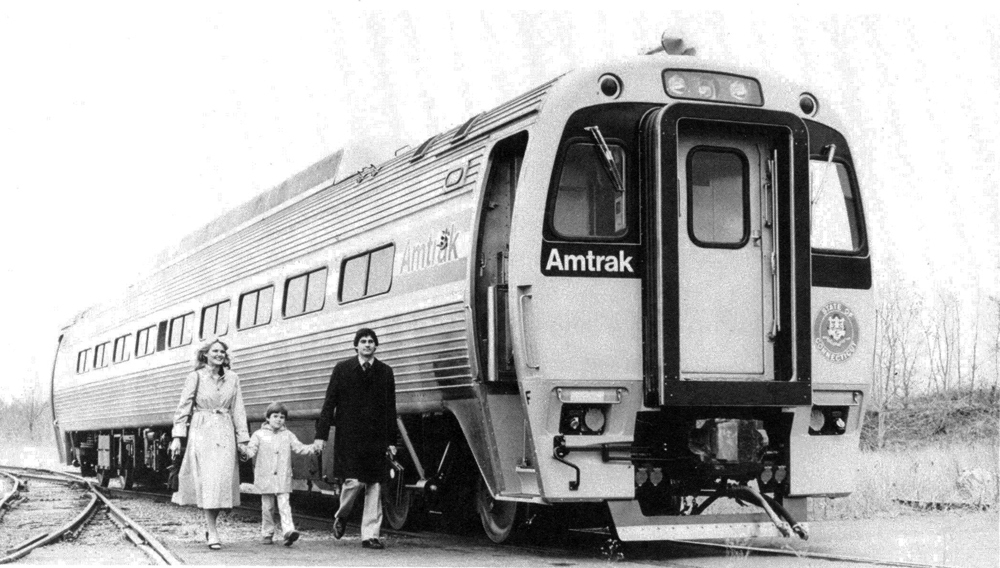

Every time I rode NYC’s New England States and later its successor, Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited, I’d stay up for Buffalo. Deep down inside I knew it had long outgrown its usefulness. Even still, one night shortly after it was closed by Amtrak in 1981, I felt the sting of disappointment while aboard the Lake Shore Limited to Chicago — the train slowly glided past it, as if out of respect; a peaceful and deserted sleeping giant; the network of red dwarf signals remaining as silent sentinels amidst the darkness — signals displayed for trains that would never traverse its maze of tracks again. The dimly lit signal towers at both approaches, massive and solid in their own right, were manned by contract, but now only paladins of memories of what once was. I pondered BCT’s future.

One bright day

Fate allowed me to travel to Buffalo as safety director for the Guilford Rail System (at that time three rail companies: Maine Central, Boston & Maine, and the Delaware & Hudson) in June 1987, long after the station had been closed for good. Having concluded my trip’s business, I was with a trainmaster who was familiar with the area and I asked if we could see the terminal up close.

We drove to the station and parked underneath the concourse by the platforms and tracks, still intact and accessible at that date. With some time at my disposal, I took a walking tour of the deserted platforms. The building itself was locked tight.

As I strolled, I recalled Garnet Cousins’ marvelous article in Trains Magazine about “The Building Beautiful in Buffalo,” and the countless photos of the complex I had seen. Here I was walking among modern archeological ruins, which until comparatively recently had once been a part of contemporary transportation. That day, silent, abandoned, and ignored except by vandals, the terminal was passed daily by trains of Conrail and Amtrak — heirs of grand traditions in railroad history.

Who today would conceive that a railroad would be inspired to invest considerable funds to create an art form, representative of an industry’s prowess? Railroading has never since been as proud to create something as grandiose, possessed of such grandeur.

After taking pictures from every possible angle, although not from the concourse, I returned to my colleague. A local police officer had joined him. I suppose we were trespassing but the officer had only stopped to inquire about our activity. Once we explained ourselves, he reminisced about his youth recalling the station as a beehive of activity. “They were good times,” he added.

Fast forward

Back in Detroit, the Ford Motor Company (which probably did as much as General Motors and Chrysler to put America’s passenger trains out of business) under the guidance of its president, William Ford, bought the building and restored it to its former magnificence, envisioning that its revival will serve to rejuvenate the community. It doesn’t matter that trains no longer start or stop there — or what high-tech businesses are conducted there — the building is alive and thriving.

Ford’s revival of the terminal begs a larger question: What are the roadblocks to restoring “The Building Beautiful in Buffalo?” BCT may be in better condition than was Detroit’s Michigan Central Terminal. Can a benefactor be found to do in Buffalo what Ford has done in Detroit?

In Buffalo, the terminal remains intact, although over the years it was stripped of its Art Deco ornaments. A dedicated local preservation group holds periodic events there and conducts an annual clean-up event to maintain the facility. New windows were installed years ago, although many remain broken, and there is electric power, although the heating plant is gone so the station and its grand hall are left exposed to the ravages of weather. It has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places and as such it will be preserved, but in what condition as time advances?

Frank Lloyd-Wright once remarked, “Architecture is our gift to the future.” BCT is a representation of our inheritance. As a nation, have we lost the ability to appreciate and treasure great architecture? Do we lack the imagination and resources to find new uses for these architectural masterpieces?

One can see what has been accomplished in Kansas City, St. Louis, Scranton, St. Paul, Cincinnati, and now Detroit, but also other cities where such structures have been repurposed. Buffalo’s grandest deserves a future, too.

Don’t believe there is any major corporation in Buffalo, like Ford in Detroit, that could use or finance the station.

The area will lilkely remain as is, in gentle decline, as a monument to the inability to predict the future. Had New York Central possessed such a crystal ball, it never would have built the station.

On the freight side, who would have predicted the demise of the huge, double-hump Gardenville yard, on the NYC bypass around Buffalo? It is so far gone that the area is unrecognizable as a location for a former huge yard. And now, even five-times-smaller Frontier no longer humps traffic.

I got to see the old station before Amtrak abandoned it. It is a grand structure that deserves to be reused in some way. The problem I see is both its size and location. It is located far from downtown and would take large amounts of money to either repurpose it as an event and office space or even residential in the old office tower. It is impressive where the old ticket and large waiting room were and I am sure the views from the old office tower would be great. However is there a major business in the Buffalo area willing to try to do a project this big.

At least it survives and hopefully will eventually see better days. No such luck for neighboring Rochester which also had a beautiful station but was 2/3rds demolished in the 60s with the final blow in the 80s.

I grew up 2 streets from the Kensington viaduct in North Buffalo which was used by the Erie Lackawanna. In the mid 60’s there were times when the 2 sets of double track would be used. The best part was when the train would service the the old Harrison Radiator plant. Further north was the trestle where one set of tracks turned westward towards the international railroad bridge to Canada while the other set would travel north to Niagara Falls. Us teenagers would “hop” the trains in frigid winter days and we actually got to see the inside of a caboose. If you wanted to prove your courage as a youth, you’d stand in front of the viaduct cement base as the locomotive would speed through. The roar and immensity of the locomotives were always too much.

I think if, like Detroit, there is no requirement that trains must stop at the station, the office space alone would be reason to refurbish it. The “grand concourse” could become a meeting place similar to the Michigan Central station, and all of the former arrival and departure yard repurposed into new developments that compliment the old. It just takes someone with enough vision AND financial horsepower to pull it off.