Stand by, helpers

While my life is beyond the daily grind of being a working railroader, there are three things I miss:

- No. 1: The sound, which I can still get while out railfanning.

- No. 2: It took me many years as an engineer to realize I missed working as a conductor with a caboose.

- No. 3: The last would be working helpers.

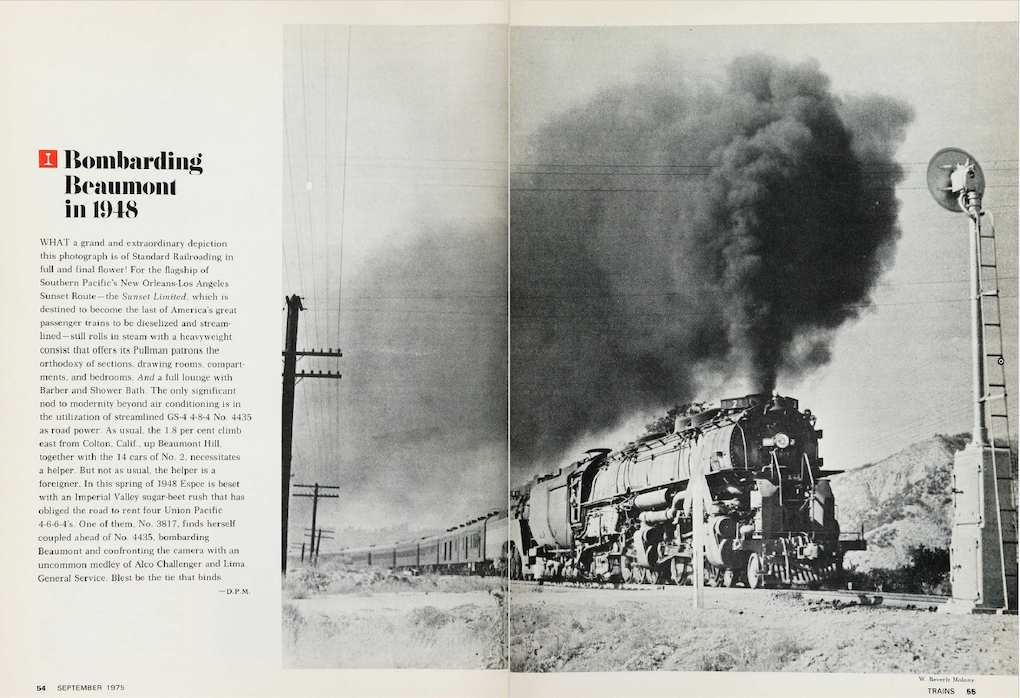

For me, there is nothing better than listening to a train fight upgrade with the raw power and sound of overcoming gravity. I was once asked what I thought of distributed power versus manned helpers; my reply was “my camera does not care.”

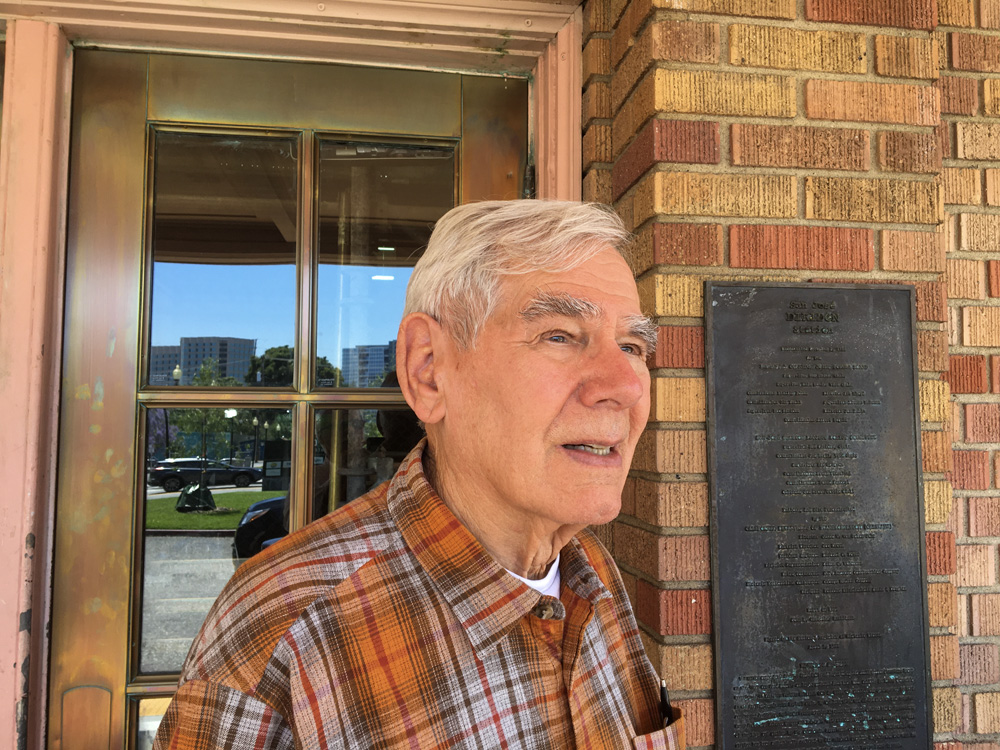

When I was a student engineer in 1990, one of my instructors had been a regular helper engineer in Wenatchee. Helpers had mostly disappeared by this time; however, on rare occasions they were still called. Thus, I was given the opportunity to gain experience about how to run helpers, which came in handy when I ended up working the Mojave Subdivision in 1998. BNSF had put on a job at the top of the hill at Tehachapi. Two units were stationed and sat in a house track next to an old freight shed a few blocks east of the old Southern Pacific Depot. If there was any trouble with a stalled BNSF train, the Union Pacific dispatcher (BNSF trackage rights between Kern Junction in Bakersfield and Mojave) would call on these helper locomotives. The set would then go down to the stalled train and assist it to the top of the hill to keep the railroad fluid.

This was necessary due to a large trackwork project. Union Pacific was installing concrete ties on the west side of the hill of Tehachapi Pass. This resulted in both the BNSF and Union Pacific running 24 hours’ worth of trains in an 8-hour window. There were a lot of trains running into hours-of-service issues. While the BNSF followed the ATSF practice of more and shorter trains, the Union Pacific followed the SP practice of longer and heavier trains.

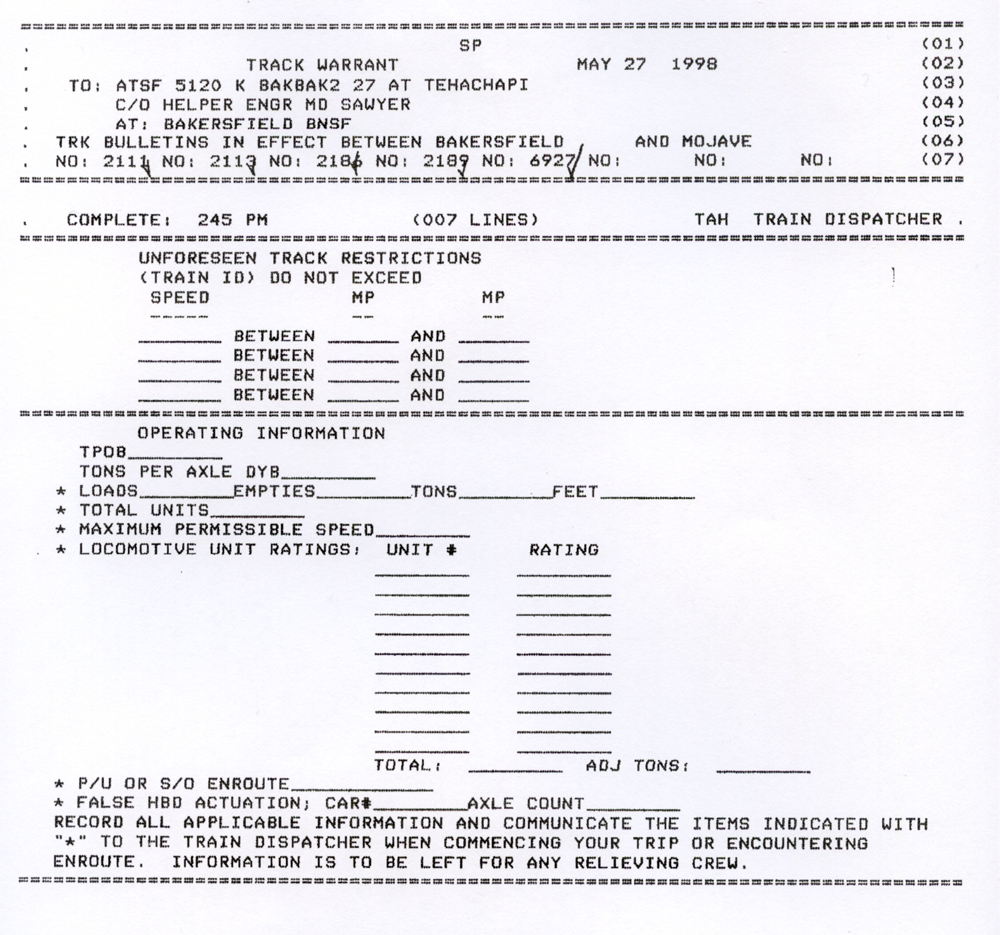

On May 27, 1998, I was called for the train symbol of KBAKBAK-27 (K for helper and Bakersfield-Bakersfield of the 27th), known as the “Standbys” on duty at Bakersfield. When I got to the yard office, I stopped by my road foreman’s office to have a brief about an air test and what to do. I started talking about tying the train and power down to do the air test on the power after I got it all coupled together. He smiled and said, “Just doublehead the power, it saves a lot of time.” I had never done that, but later that shift I was going to, in fact, find out how that worked. I asked a few more questions before my conductor and I caught a taxi to Tehachapi to, well, stand by.

Well, sure enough, we did get a call 10 hours into our shift. We started down the hill to rescue an eastbound BNSF train that had stalled near Marcel. We lined the power out to the main line and headed west to the stalled train. It felt a bit strange to me that as the helper engineer, I oversaw the rescue with a more senior engineer on the stalled train — with the helpers on the point, the helper engineer is then in charge. I had been thinking all afternoon about what I would have to do if needed. I had a plan that I was hoping I would not have to use.

We doubleheaded, as the road foreman had told me. Just like the steam days, both engineers would run the power independently of each other. We did have the train line cut in but nothing else, so if there was an emergency brake application that had to be initiated by one of us it would work on both sets of power and train.

We had a safety brief. I told the stalled engineer, “OK, here’s how it’s going to work. I’m going to kick the air off and I want you already in throttle 3, I will also be in throttle 3 and slowly adding more throttle, watch your amps and try to match me.” By watching the amp gauge (the power being supplied to the traction motors), you increase throttle as the meter goes down or decrease when the amps start to go up.

As the air released, we ever so slowly started to creep forward. We got it rolling and marched right up the hill. At the top of the hill, we uncoupled our power and put it back in the house track. The taxi was waiting to take us home to Bakersfield.

I have often made the joke that I knew two mountain grades at home. They were mild compared to Tehachapi. I have always said you could not come home to Seattle a worse engineer than when you left Seattle. I gained a ton of experience as an engineer down there.

Check out previous column, “An engineer’s life: Free steak and eggs.”

ATSF 5120 is still on BNSF’s roster. Now #1892.

Cool, that’s good to know. Thanks.