Combine culinary style of the late 1800s, the taste of one railroad magnate and the inspiration of another plus throw in a touch of crazy. The result is an attempt to satisfy a national craving for oysters. The old saying stands that necessity is the mother of invention. In this case, the need was finding a means to transport fresh, live oysters from the eastern U.S. coast to the interior in order to satisfy the “needs” of the upper class. Being that the railroad was the long-distance transportation method of the day, a number of experiments were tried leading to a specialized car for oyster transportation.

Come along as we explore five mind-blowing facts regarding the Stilwell oyster car.

No. 1 — Pass the oysters, lots of them!

In America today, a burger and fries is as popular and ubiquitous as oysters were in the 1800s. Currently, we devour over 50 billion hamburgers annually, which works out to around three per week for each of us. From the oyster menu, however, Americans average less than three per year per person. By contrast in the 1800s, New Yorkers alone gobbled an average of 600 oysters per person annually. From 1880 to 1910, the United States harvested over 160 million pounds of oysters each year.

In 1868, Long Island Rail Road tracks were laid into Sayville, N.Y., about half way out along the south shore of Long Island. Two years later, oysters were being shipped by rail from Sayville to New York’s Fulton Fish Market, which was selling 50,000 of them daily. Between 1900 and World War I, the Long Island Express Co. sent oyster express trains from the Sayville area into the big city at 9 and 11 a.m., and 2 and 5 p.m. An order received in the 7:30 a.m. mail would be on the 9 a.m. train and could be delivered in Brooklyn around 12 p.m.

During this time, American ate oysters in just about any preparation, from raw to stewed, from fried to stuffed in roast turkey. It seemed that just about any recipe was tried — at least once.

No. 2 — Are the voices in Mr. Stilwell’s head inspiring you?

Cue the creepy “Twilight Zone” theme music … For your consideration: Arthur E. Stilwell (1859-1928) went from rags to riches and back again. And, by his own admission, it was the fairies, brownies, and other voices in his head that encouraged his accomplishments.

The voices directed Stilwell, born in Rochester, N.Y., to Genevieve Wood and recommended marriage. Stilwell was working as a teamster and with enough skill was promoted to a clerk. His in-head audio directional system next pointed the way west, telling Stilwell he should build railroads. The young couple moved to Kansas City, Mo., where Stilwell, in his 20s, worked in a brokerage firm, learning about business and banking. Soon, through a large bank loan and shrewd real estate dealings he possessed the resources to build the Kansas City Beltline Railroad.

His fairies and brownies next instructed Stilwell to extend the railroad to Texas and the Gulf Coast. The Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf — forerunner of the Kansas City Southern — headed toward Galveston, Texas. The voices, however, had bad vibes about the city and directed Stilwell to choose a different port city. The railroad was built further south and the city of Port Arthur, Texas founded as its port. (Port Arthur named for Stilwell.) The voices were correct about Galveston, for in September 1900 the city was devastated by a massive hurricane.

In his time, Stilwell built more than 3,000 miles of railroad and founded 40 towns.

On Sept. 26, 1928, Stilwell suffered an apoplectic fit and died. At the time, his estate was valued at $1,000. Genevieve, distraught over Arthur’s death, leapt to her death from their apartment window just 13 days later. Mysteriously, the cremains of both Arthur and Genevieve disappeared from the mortuary before they could be memorialized.

No. 3 — They’re dead!

The oyster beds American’s were tapping into during the 1800s lay along the ocean coast lines. One of the largest beds could be found in the Chesapeake Bay. Oysters shipped to growing Midwest cities like Chicago, St. Louis or Kansas City were shucked (removed from the shell) at packing houses near the harvest site. At peak production, Baltimore had nearly 30 sucking-packing houses to process Chesapeake Bay oysters. Over time, the sucked meats were packed in wooden boxes, barrels, or large metal pails mixed with ice and salt water for railroad shipment inland. Additional ice was packed around these shipping containers during the trip.

The challenge was maintaining that briny, salt-water taste oysters are noted for. While shipments were handled as express in passenger trains, a small percentage arrived dried or lacking the proper taste. Additionally, depending on the time of year and size of the harvest, oysters could sit at the shucking house for a week before processing.

There was a demand among Midwestern social elites to have oysters as fresh as those being served in East Coast cities. This meant shipping oysters live in their shells. The trick was keeping them fresh and live during the trip.

Due to demand, oyster shipments in the 1800s received a great deal of attention, especially when it came to derailments. The oyster status was often included in a newspaper’s account of an incident. The New York Times from Dec. 11, 1854, wrote: “On Friday last a train on the Central Ohio Railroad was thrown off the track, the engineer killed, and a fireman fatally injured. The locomotive, baggage, and an oyster car, were smashed to pieces, but fortunately none of the passengers were injured.”

No. 4 — Mr. Pullman likes oysters

George Pullman, of sleeping car fame, no doubt was successful. While his attitude toward those who worked for him and built his fortunes was less than generous, Pullman wallowed in luxury. He demanded the best for himself and chosen guest. Those that could afford to travel in some of the first Pullman palace cars, were also surrounded by luxury in accommodations, service, and dining.

As noted, oysters were a dish of the times. The quality of your oysters and how they were prepared was a signal to your social status and wealth. Pullman dining car menus prominently featured oysters in a number of upper-class styles, including fresh, raw on the half shell. Pullman, himself, also liked oysters, preferring them fresh.

No. 5 — First-class oyster accommodations

Considering the facts laid out in points one through four, the challenge in the late 1890s was transporting the bivalve mollusks of the Ostreidae family alive and fresh from their salt-water beds to the elite classes of cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City.

Previous attempts to develop a railcar specific to oyster transport had failed. Tanks cars were tried, however, the internal temperature could not be controlled generally resulting in overheating the oysters. In 1866, the B&O constructed several special express cars to speed live oysters packed on ice to Wheeling, W.Va., Cincinnati, and Chicago. At the time, it took 50 hours to reach Chicago — far longer than oysters would stay fresh or alive on ice.

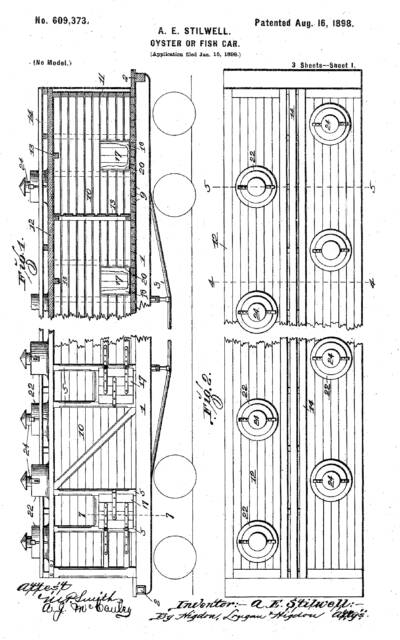

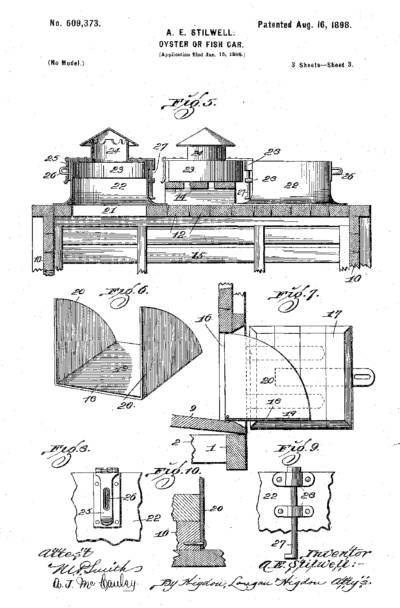

Whether with the aid of the head brownies and fairies or other humans, Stilwell solved the oyster transport problem, or so he thought. The plan was for a car traveling in passenger trains designed specifically for oysters. “The Stilwell Oyster Car,” as was proclaimed in 13-inch-tall silver letters on the side of the bright blue vehicle was built by Pullman in 1897 — remember Mr. Pullman liked oysters. The car was an immediate hit in the press, traveling on Stilwell’s Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf from Texas to Kansas City, the shipping results were less than expected.

To use a contemporary term, the Stilwell Oyster Car looked like a vertically-challenged boxcar. From its 34-foot-long deck, resembling a flat car, stood a 5-foot, 3-inch structure with eight metal vent-hatches protruding from the roof. Inside, the car was divided into four tanks. The sides were fabricated from three-inch thick white pine with a layer of cork insulation. The tanks were sealed with pitch in the same manner a ship was made water tight. Oysters were loaded via the roof vent-hatches. Each compartment had two small openings along the side at the bottom for unloading. The openings were fitted with small, thick doors and a retractable chute. Once the oysters were on board, the tanks would be filled with 8,200 gallons of the same water from which the mollusks were harvested.

Newspapers across the Upper Midwest and East raved about the new car and the hope of its fresh, live cargo. Alas, hopes were dashed as the Stilwell Oyster Car was plagued with many of the problems that curtailed previous attempts. Temperature control, rough handling, and transit time delivered dead oysters seriously lacking in freshness.

Stilwell’s Oyster Car was labeled as “Car A.” Records indicate that a “Car B” had been ordered. With the first car’s failure it is not completely clear if the second was built. Some indications are that it was, but that it was destroyed in a train wreck shortly after construction. A final irony in the oyster-transport tale is that on the day he died — Oct. 19, 1897 — George Pullman had a meeting scheduled with Stilwell to discuss among other things the oyster car. The meeting did not take place.

The Stilwell Oyster Car is remembered today in a model kit produced by Conowingo Models. The Model Railroader crew offers some details on the kit in this review.