When I first started at Model Railroader in February 2014, I edited a story by Alex Marchand about how he created N scale hoppers using 3-D printing. That story was where I began to learn the basics of 3-D printing. But things have come a long way in the decade since. What was once a niche in the hobby has become popular with modelers and manufacturers.

Why 3-D printing?

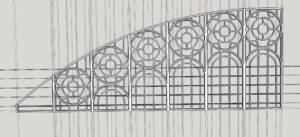

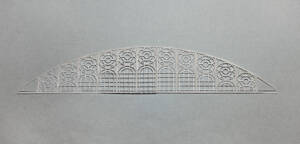

For modelers, this can be a great way to make complex shapes that require lots of repetitive steps. My first project was a large window for the end of a trainshed. I could have cut pieces of styrene strip to make the window, but getting everything neatly aligned would have been tedious. Using a then-free computer-aided drafting (CAD) program called Sketchup, I drew the window, then sent it to a company called Shapeways, (which has since ceased operations) to be printed. A decade ago, high-quality home printers were too expensive for most hobbyists, but that has started to turn around.

For manufacturers, the advances in 3-D printers means it’s possible to make products that can be difficult to tell apart from injection molded plastic models. This offers a great savings as much of the cost of new products is in tooling, often costing tens of thousands of dollars for the molds needed to make a model. With 3-D printing, there’s no mold. Each individual product is created on a printer bed or tank.

How does 3-D printing work?

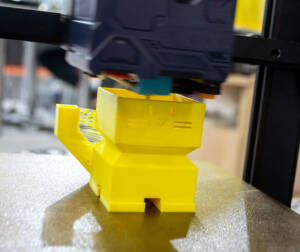

There are several ways 3-D printers work. You can find a detailed explanation here. The one hobbyists often think of first are filament printers, also known as fused deposition modeling (FDM). These printers use a roll of plastic filament, which is fed into a hot nozzle, then deposited on a plate known as the print bed. These are the least expensive printers, and make fairly rough models at the lower prices with noticeable textures from the printing. They also require a support structure while printing to hold up the model while the hot plastic cools.

For most modeling, inexpensive versions of these machines would be considered too crude to use for detailed models, but they’re fine for making things such as throttle pockets or switch machine mounting pads. Higher cost filament printers that create thinner layers can produce simple models, but compound curves still have visible layers that can be difficult to remove or camouflage.

Stereolithography (SLA) printers use a laser to harden liquid plastic on the build plate. These machines offer much higher levels of detail and smoother curved surfaces than most filament printers. This is the most common type used by hobbyists at this point.

Polyjet printers also deposit plastic, in much the same way as an inkjet printer deposits ink, but the material is hardened with ultraviolet light. These machines use powder instead of filament and can create finer detail. These are proprietary machines offered by a company called Stratasys. Polyjet printers are capable of printing items in full color, clear, or flexible materials.

Selective laser sintering (SLS) also use powdered material, usually a type of plastic. An advantage of SLS printing is that it doesn’t require a support structure during printing.

Other methods allow for different types of materials, including metals such as steel and aluminum, but these are usually used for aerospace and automotive parts where durability and precision requirements are several steps above what most modelers would ever need.

One of the disadvantages of 3-D printing is that there’s no economy in printing larger numbers of parts. It’s unlikely we’ll see 3-D printed household items that sell in the hundreds of thousands or millions of units, but for model railroading, where product runs for injection-molded items such as locomotives and rolling stock are in the thousands, a method such as 3-D printing that can produce dozens or hundreds of niche items makes sense.

What’s needed?

Besides a printer, you’ll also need the files to run the printer. Sometimes, you can find what you’re looking for online at sites such as thingiverse. Some designs are free, while others must be purchased. Usually, the cost is significantly less than it would be to buy a completed item, and depending on the files, you may be able to modify it to better fit your needs.

If you want to create your own designs, or modify someone else’s, you’ll need design software. I started with Sketchup, which I found easy to use, and was well-suited to making architectural shapes. However, there are more programs now available. Ben Lake, from the Trains.com video team, was using Blender for a while.

Once you have your files, you’ll need what’s called a slicer program. This will allow you to set up the design to print on your printer. Most printers will include a rudimentary slicer program, but Tim Kidwell of FineScale Modeler prefers the Lychee Slicer. This is what he uses to prepare files for the Anycubic SLA printer the FSM team has been using.

Tim offered a few tips for using an SLA printer. It works best in the same environment people like to be in, so about 70 degrees Fahrenheit with low, but not absent, humidity. Because it uses ultraviolet light to harden and cure the resin, it works best in a dark room away from natural light or UV light sources. It’s also capable of producing strong odors, so you’ll want plenty of ventilation.

There are also places where you can go and print your own files. The local library in Waukesha, Wis., for example, has a technology lab with 3-D printers and laser cutters. Some commercial businesses also offer access to these machines. Check online to see what might be available in your area and what sort of files you’d need to provide to run the machines.

Sounds like work

The thing to remember about 3-D printing is that there’s still work and skill involved. It’s just another tool. It can do some things really well, but it’s not the only tool you’ll need. And although prices are coming down, quality 3-D printers are still an investment of at least a few hundred dollars.

Sometimes it makes sense to purchase what you need already printed. One such company, specializing in models for fans of the Soo Line, is former Model Railroader DCC columnist Mike Polsgrove’s SooParts. Other companies exist that make parts for specific railroads, specific eras, or aspects of modeling, such as freight cars or road vehicles. Whether you decide to print models yourself, or purchase parts to build larger projects, it’s likely you’ll be working with 3-D printed products on your model railroad soon, if you haven’t already.

A great deal of the work involved these days is doing the research on the prototype.