24th Mechanized Infantry Division

The first sergeant’s voice boomed out over the formation: “I’m looking for eight volunteers. I need eight men who are looking for an adventure to volunteer for a special assignment. Don’t everybody step forward at once.” Not surprisingly, no one was inclined to volunteer until they knew more about what they were getting into.

The past months had been busy for the 24th Infantry Division at Fort Stewart, Ga. A year earlier, the unit was regular infantry with jeeps and light trucks. Now the division worked feverishly exchanging light equipment for tanks and armored personnel carriers. Even the unit’s name was updated — 24th Mechanized Infantry Division.

The next step for the new mechanized division was a major training exercise. Fort Drum, N.Y., was selected for a January 1980 event. Located close to Lake Placid, the site for the upcoming Winter Olympics, Fort Drum would provide a different climate. There might be snow, something many of the soldiers had not experienced.

Joining Fort Stewart soldiers would be units from the 194th Armored Brigade (Separate), Fort Knox, Ky., as well as units from Fort Bragg, N.C.; Fort Huachuca, Ariz.; and Scott Air Force Base, Ill. The equipment move was a logistical challenge. All of the division’s heavy equipment would need to be transported nearly 1,100 miles from Fort Stewart to Fort Drum.

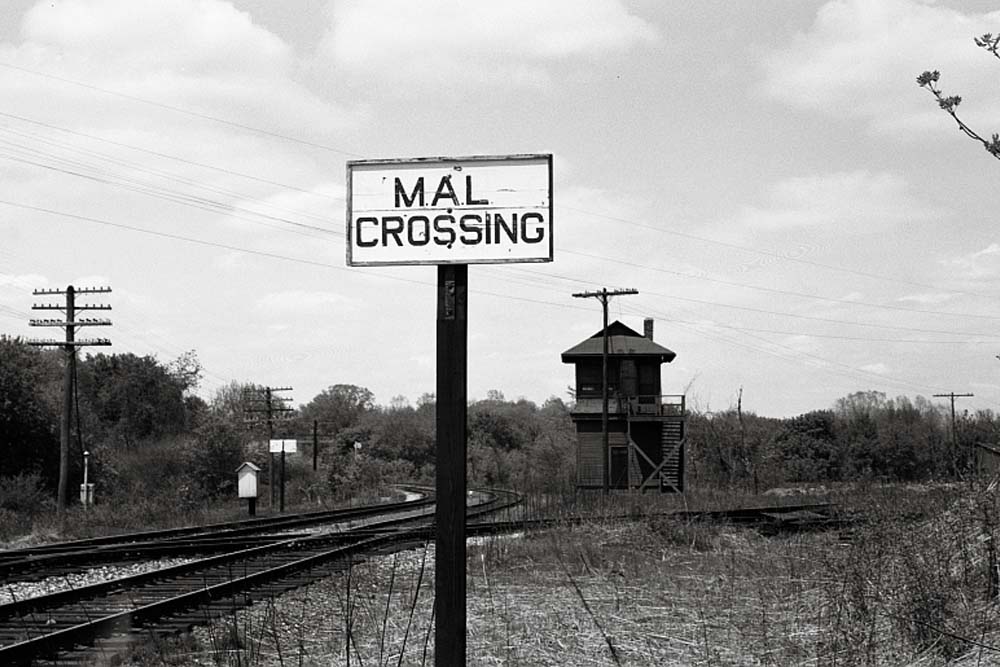

Rail transportation is often best for deploying a large, mechanized infantry or armored unit. Soldiers routinely train on all aspects of loading and unloading such rail movements. Experienced noncommissioned officers and railroad personnel provide supervision and hands-on training.

Routinely, in the early 1980s, a detachment of soldiers traveled along to provide security and logistical support. For the rail movement between Fort Stewart and Fort Drum, eight soldiers would serve as rail guards or “supernumeraries,” the military term for personnel accompanying shipments by rail or sea. Six served as guards, one would be the cook and a sergeant was in charge of the detail. A caboose was provided by the railroad, which had room to sleep four at a time — more or less comfortably — a simple kitchen setup, a toilet, and a coal-burning stove.

The supernumeraries boarded the train at Fort Stewart and stayed with it to Fort Drum. The rail movement was tentatively scheduled to begin a week before Christmas. Transit time was estimated at three or four days, putting the eight soldiers in Fort Drum a few days before Christmas and nearly two weeks before the rest of the unit was due to arrive via Air Force transports.

In the end, the first sergeant had no trouble getting volunteers. It was a chance at an adventure, operating as a small team on an important mission. It would mean being away from family over the holidays, but that was part of military service. Being a staff officer in the division logistics office, I did not volunteer, but monitored the train’s progress from Fort Stewart.

The team was brought together, briefed on its duties, and began preparing the caboose. A set of portable radios with sufficient range to reach both ends of the train was issued, so guards could conduct a walking patrol when stopped. It was decided the team would not carry rifles but would instead be equipped with axe handles. The axe handles would be a sufficient symbol of authority and provide a means for basic self-defense.

The cook was given help planning menus and stocking utensils and food to cover a week, even though the trip was expected to take no more than 3 days. As a backup, several cases of MREs (meals, ready-to-eat) were loaded.

In an abundance of caution, one of the soldiers was designated as a Class A agent, authorized to make limited purchases in special situations when normal procurement processes are not practical. The Class A agent sets up a purchase, looking for fair prices and quality products. A second person, who has been entrusted with a small sum of cash, pays for the purchase, saving the receipt to turn in back at their home base in order to balance the books.

Despite this cautionary measure, no one realistically expected any trouble. A person could drive from Fort Stewart to Fort Drum in a couple of days. Surely a train could cover that distance in three to four days.

The 26-car train was loaded and cleared to depart Fort Stewart about a week before Christmas. A local TV news crew came out and captured video of the train rolling by, loaded with tanks, armored personnel carriers, and heavy trucks. The rail guards were seen waving from the caboose as it rolled by.

The news then cut to coverage of the Soviet Union’s ongoing movement of military forces into Afghanistan. One network broadcast showed Soviet tanks in the snow in Afghanistan, juxtaposed with the movement of vehicles from Fort Stewart heading to Fort Drum for winter training.

Back at Fort Stewart, the division headquarters was monitoring the movement of the train as it headed up the East Coast, quickly learning that military trains do not enjoy a high priority. Over and over the Fort Stewart train would be put into a siding and the train guards would find themselves watching other trains pass.

The days dragged by. The train moved pretty fast when it moved, but that wasn’t often. It seemed that the train would just get started moving at a good clip when it would slow down to take another siding.

After nearly a week, the train had traveled across South Carolina, North Carolina, and just entered southern Virginia. The guards speculated they could have walked that distance faster.

As Christmas Eve drew closer, the team found themselves low on supplies. They had gone through the better menu choices in the galley and had resorted to eating the MREs.

Worse, the coal was running low. The guards had been generously feeding the stove, thinking the supply only needed to last a few days. As days dragged on, the possibility of running out of coal became a major concern.

On Christmas Eve the guards received mixed news from the train crew. The train would not be moving on Christmas Day. It was heading into the Petersburg, Va., yard, where it would stay until Dec. 26. The crew tried to soften the blow by pointing out that Petersburg is immediately adjacent to Fort Lee, one of the largest Army bases on the East Coast. Perhaps the guards could catch a ride to the base and eat in a real mess hall and sleep in a real bunk.

The sergeant of the guard nixed that idea. The guards would remain with the train. Even if the train was inside the rail yard, the mission was to ensure everything remained secure. However, groceries and coal would need to be restocked.

The train crew directed the sergeant to the Petersburg yardmaster — someone they were familiar with and knew he had experience working with the military thanks to nearby Fort Lee. If anyone could help, it would be the yardmaster.

The crew disconnected the power, leaving the eight supernumeraries to spend Christmas in a cold, dark rail yard.

The sergeant and cook headed out to find the yardmaster. It was getting late on Christmas Eve when they found him in his office. He quickly took charge, figuring out how to get coal and groceries delivered.

The Sergeant kept a running tally of how much this was going to cost the team. Thanks to some finagling by the yardmaster, they were able to keep the costs well within the budget. But when the Class A agent went to pay, the yardmaster held up his hand and refused to accept cash. The team was still hundreds of miles and potentially days from reaching its destination. He pointed out that the train might face more delays as it neared the nation’s capital and beyond. He insisted the team keep its limited funds just in case. Besides, he pointed out, he worked with the purchasing office at Fort Lee all the time. He didn’t expect to have any problem getting reimbursed.

The encounter with the yardmaster was a turning point for the team. He made sure they had plenty of food and drink, along with a full load of coal. The guards were well fed and stayed warm and dry on Christmas, even though they were miles from home and family.

On Dec. 26 the train was underway again. The remainder of the journey was uneventful, with fewer and shorter delays, so it seemed. The train arrived at Fort Drum a couple of days after Christmas.

The training exercise at Fort Drum went well. The weather continued to be unseasonably warm with little precipitation until the next to the last day of field maneuvers. Then the skies dumped snow, snow, and more snow. Anybody who had hoped for lots of snow got their wish. And those who did not had nearly two weeks without snow, so it all balanced out.

When training was over, the process was reversed. The train was loaded, a team of rail guards assembled, and the equipment rolled home to the warmer Georgia climate.

Early that summer, the division logistics officer answered a call from the procurement office. In question was an invoice from the Petersburg yardmaster for services rendered to a transient shipment on Dec. 24. The colonel assured them the bill was legitimate and should be paid. No, sir! Sorry. The proper procedure had not been followed. The purchasers should have obtained three competitive bids and followed standard contracting protocol. That the provider turned down the Class A agent’s cash payment violated the fine print of some government regulation. Much paperwork was now needed in order to pay the yardmaster.

Months later, when the logistics officer briefed his replacement on outstanding issues, the yardmaster’s still-unpaid bill came up. The incoming logistics officer promised to make it a top priority.

When Christmas rolls around, we are sometimes reminded of the yardmaster who went out of his way to help eight soldiers far from home. We would like to think he was eventually made whole for his services and for the way he went above and beyond the call of duty. Maybe he did get paid; then again, maybe not. If nothing else, his efforts were then and still are appreciated by the eight soldiers and those of us who know the yardmaster’s story — a gentleman who helped some cold and lonely soldiers at Christmas.

Tanks are a wide load and have special routing instructions. The RR’s have typical routings prepared in advance.

I’d have had a beef and beer at Ft. Stewart (or at an off-Post VFW) to raise money to reimburse the yardmaster off the books.

The kind of service given that military train was one reason the industry had developed a bad reputation among all shippers. Its pathetic they could not have given it top priority. Hopefully they learned their lesson from that era and are providing better service to our armed forces today.