What happened to the caboose? Many factors helped seal their fate, and the demise of the caboose has been mourned in many places, including in the pages of Trains, which bid farewell in a special issue in August 1990. But the caboose hasn’t disappeared. Even today, you can find a few cabooses still at work. The caboose might be a rusted warhorse limping along behind a local, or it might be tidy, lavishly equipped, and fleetingly glimpsed at the end of a mainline freight. They’re the last of their kind.

Cabooses sheltered the train crew, made switching more efficient, and played a vital role in safe operations. To understand why cabooses have been largely sidetracked and why some are still used, it helps to remember why cabooses were invented.

Origin

The story of the caboose dates to the early days of railroading. In the 1840s, a boxcar with a desk for the conductor and space for his tools and supplies was part of the consist of an Auburn & Southern (later part of the New York Central system) mixed passenger and freight train.

Early railroads also built rough shanties on flatcars. The familiar cupola was invented around the 1860s, originally as an addition to the conductor’s boxcar. The basic form of the caboose was largely settled by the 1880s, although individual railroads had their own ideas about the size, color, floor plan, cupola placement, and a myriad of other details.

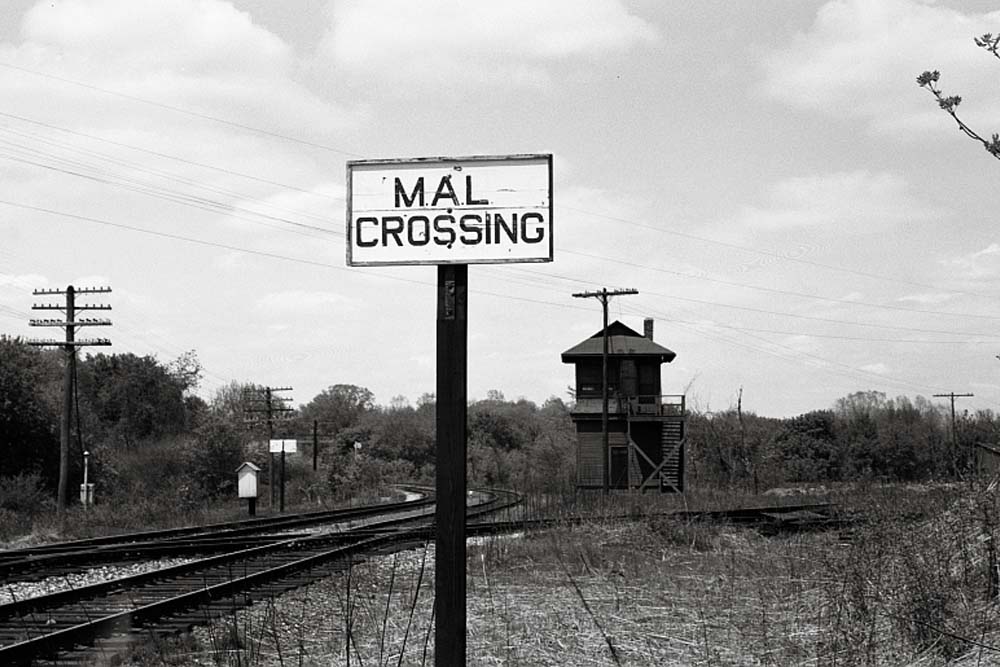

From their outpost at the rear of the train, the conductor and brakemen were well positioned to watch for hotboxes and dragging equipment and to provide flag protection when the train was stopped on the main. Having people at both ends of the train also made fast work of switching.

In densely populated parts of the country, cabooses were tool cars, lookout posts, and offices. They were all that and more in less-settled areas, particularly the American West. In places where bunkhouses and 24-hour diners were few and far between, the caboose — suitably equipped with bunks and a stove for heating and cooking — was the crew’s home away from home.

In his book The Railroad Caboose (Golden West Books, 1968), railroader William Knapke recalled a time when a caboose would provide shelter and three meals a day to five or six men for perhaps four or five days at a time.

“A typical caboose,” Knapke wrote, “would carry one or more hams, a huge side of bacon, sacks of flour and sugar, a bushel of potatoes, some onions, ample coffee, and canned goods. Four or five large wheat sacks filled with coal would be lashed to the running board, and there would be a triple supply of kerosene.”

But times change. Until the 1960s, it was common for a crew to have an assigned caboose. This caboose had to be switched out of the train at every crew change. Gradually, railroads won approval for pooled cabooses, which stay attached to the train for the entire journey. No longer would crews live in their caboose between runs.

Just as air brakes put an end to brakemen stopping trains by tightening hand brakes, lineside detectors and rolling stock improvements made the need to have a watchful eye at the rear of the train less important. The nature of the work also underwent changes. Having workers at both ends of the train to line turnouts and connect air hoses makes for efficient setouts and pickups, but a unit train or other through freight can be handled by just an engineer and conductor; both riding the locomotive.

Transition

Starting in the 1980s, cabooses were largely replaced by automated end-of-train (EOT) devices.

A few cabooses remain in service on short lines, and Class Is use them on trains that have lengthy backup moves to provide a place for a crew member to stand and serve as a lookout for the engineer. For many railroaders and railroad fans, it’s just not the same. Even the name is not the same, on some railroads these cars are called shoving platforms, and some have plated-over windows and permanently locked doors.

A few cabooses have been modified for specialized duties like research or inspection. Some manufacturers of oversized or high-value shipments own cabooses, which serve as living quarters for company representatives escorting the loads. These cabooses are generally air conditioned and have modern plumbing and heating systems, televisions, computers, and a kitchenette. The representative follows the shipment to its destination, then hops on a commercial flight home, while the caboose deadheads back.

The beloved CABOOSES are definitely gone, but never forgotten!

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

Gosh, I miss cabooses.