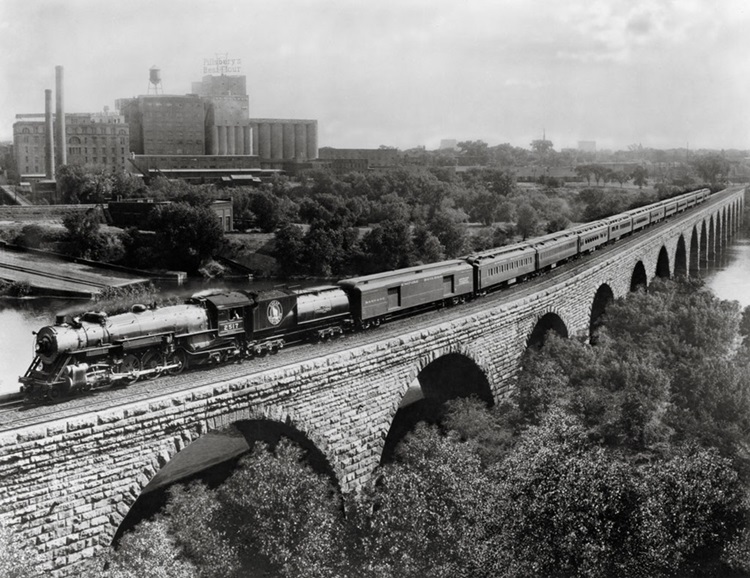

Prior to the time of the streamliners, North American passenger trains were not particularly colorful. Most sleeping cars were Pullman green, although there were exceptions; both the Pennsylvania and Canadian Pacific utilized shades of red on their passenger equipment, for example.

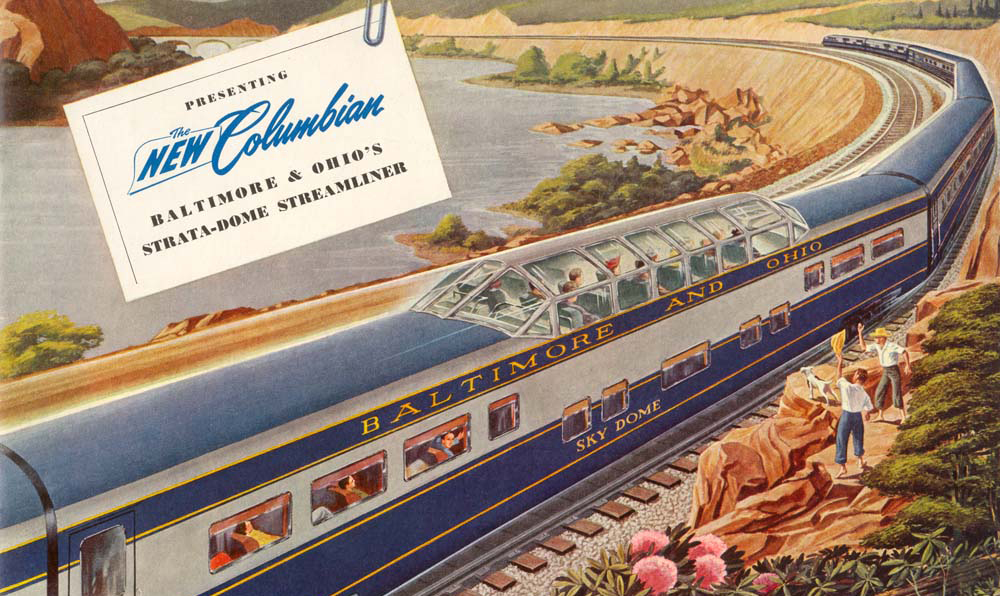

With the arrival of streamlined lightweight equipment as of the late 1930s, a rainbow of hues began to appear. Examples include the exotic scheme of the original City of Miami, the blue and cream of Missouri Pacific’s Eagles, the Milwaukee Road’s maroon-and-orange Hiawathas, alongside regional competitor Chicago & Northwestern’s green-and-yellow 400s.

So, if people knowledgeable about the era of the streamlined passenger train on this continent were asked to associate a predominant color with this type of equipment, what would be the proper answer? I’ll assert the correct choice is silver, and that a single car manufacturer, the Edward G. Budd company of Philadelphia, essentially would be the responsible entity.

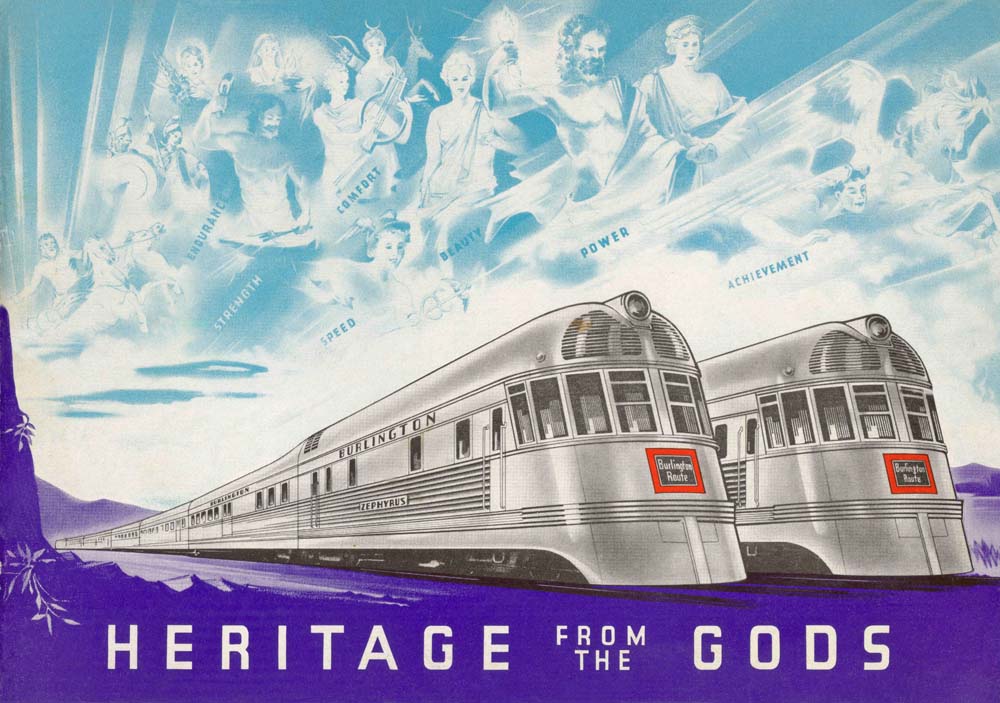

Widely acknowledged as the first two entries in this field of streamlined train are Union Pacific’s M-10000 “Streamliner,” built by Pullman-Standard, and Burlington’s Zephyr 9900, built by Budd. The M-10000 later ran as the City of Salina prior to being scrapped during World War II. It boasted a brown-and-yellow exterior paint scheme, introducing the “Armour yellow” that still adorns Union Pacific equipment today.

The other new entrant, the Burlington’s Zephyr 9900, also known as the Pioneer Zephyr, was delivered by the Budd Co. in stainless steel sans paint and would be nicknamed “The Silver Streak.” The essential message was that the unadorned silver structure featured low maintenance, as well as announced itself as up-to-the minute modern due to its shiny silver appearance. A similar trainset was delivered to the Boston & Maine Railroad, where it ran originally as the Minute Man between Boston and Portland, Maine.

Subsequently, Budd began to build “conventional,” individual-car trains, with the Burlington being an early and large customer. These trains included the original Denver Zephyr, between Chicago and the train’s namesake, as well as the second set of Twin Zephyrs between the Windy City and the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

In the East, the Reading Co. ordered a unique five-car consist for service between Philadelphia and New York City (served via Jersey City, across the Hudson River from Manhattan) consisting of a mid-train diner and a coach and observation car on each end (which obviated the need to turn the equipment); this would prove to be the Reading’s only foray into lightweight streamlined equipment.

Other Budd streamliners that predated World War II included Santa Fe’s stunning Super Chief (initially only a single set of cars), as well as a trio of trains focused on the Florida market. These comprised the Atlantic Coast Line-sponsored Champion, the competing Seaboard Air Line’s Silver Meteor in the New York-Florida market, and the South Wind between Chicago and the Sunshine State. The East Coast competitors were clad in shot-welded stainless, while the Wind, a protégé of the Pennsy, appeared in that road’s Tuscan red.

Finally, New York Central’s Empire State Express was converted to the new, shiny Budd lightweight equipment and inaugurated on that infamous day in 1941 when the U.S. was thrust into World War II.

As World War II wound down, the railroads ordered monumental amounts of new streamlined passenger equipment with the belief that the wartime traffic boom would continue, but this eventually proved to be a false hope. Budd and its stainless-steel cars benefitted significantly from this euphoria.

The NYC, for example, ordered extensively from Budd and Pullman-Standard (and modestly from American Car & Foundry). The railroad intended that some of its streamliners, including the all-coach Pacemaker, as well as the New England States, Ohio State Limited and Southwestern, would utilize Budd stainless equipment. Others, including the 20th Century, Commodore Vanderbilt, and Detroiter, would consist of Pullman-Standard smooth-side cars painted in two-tone gray.

By the postwar period, the initial all-coach streamliners to Florida had sleeping cars added. Enamored of its association with stainless equipment, the Seaboard extended the Silver Meteor’s influence, spawning both the Silver Star and Silver Comet, the latter operating between the Northeast and Birmingham via Atlanta.

While Budd’s passenger cars were constructed entirely out of stainless steel from a structural standpoint, some railroads elected to paint their exteriors in their company colors. The Pennsylvania Railroad, for example, had a fleet of 21-roomette sleepers, some dining cars (both standard/single and twin unit), and a few coaches built by Budd, all garbed in the PRR’s standard Tuscan red.

Union Pacific followed a similar paradigm, using Armour yellow for its “Pacific” series of 10-roomette 6-double bedroom Budd-built sleeping cars. Interestingly, in order to compete with the CB&Q’s installation in 1956 of “Slumbercoaches” on the newly reequipped Denver Zephyr, the UP leased a pair of those Pennsy’s 21-roomette sleepers to meet this competition; both of these cars were repainted in yellow for what turned out to be a relatively short-lived assignment.

When both Great Northern and the Northern Pacific added domes to their flagship Chicago-Pacific Northwest trains in the mid-1950s, Budd supplied the equipment, again painted to match the colorful smooth-sided cars that made up the vast majority of these trains’ consists. The NP later also acquired new Budd diners in the late 1950s, which also wore the Raymond Loewy-designed two-tone green paint scheme.

A few railroads that had only a modest association with Budd streamliners also elected to retain the “house” paint scheme in lieu of unpainted stainless. Examples included Missouri Pacific’s fleet of Eagles, as well as a pair of diners and tavern observation cars for the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western’s Phoebe Snow; these four cars were the Lackawanna’s only Budd products.

A hybrid form of decoration utilized by several Budd passenger car operators was to paint only the cars’ letterboards, leaving the rest of the exterior in natural metal. The Southern Pacific’s Sunset Limited and PRR’s Congressional and Senator trainsets (the latter in conjunction with the New Haven) used different shades of red to good effect in this manner.

As passenger trains in the U.S. declined during the 1950s, some roads that had not purchased dome cars acquired them via merger, an example being the N&W, which added them via its 1964 merger with the Wabash. In this case, the surviving railroad also adopted the paint scheme of the cars’ original owner.

The Illinois Central bought several dome coaches from the Missouri Pacific and repainted them into IC’s iconic chocolate brown-and-orange passenger scheme. Interestingly, the IC had leased Northern Pacific dome sleepers for several winter-seasons for its City of Miami train; during this period these cars were repainted twice a year so as not to mar the esthetics of the trains they were serving.

In addition to long-haul intercity services, Budd’s silver stainless look also made its way into shorter, smaller markets via the company’s Rail Diesel Car, or RDC. This included the rule-proving exception of the Western Pacific’s use of this equipment on its long-haul trek between Salt Lake City and Oakland, Calif., operating as the Zephyrette.

Budd stainless steel equipment also provided electrified commuter equipment for use in the Philadelphia region. Not surprisingly, they were termed “Silverliners,” and this nomenclature has survived the Budd Co.’s exit from the railroad passenger-car business.

In retrospect, the Burlington Route embraced the silver passenger cars to the greatest degree of any of Budd’s customers. All the road’s streamlined passenger-carrying cars that were acquired new came from Budd and wore their unadorned silver stainless-steel livery throughout their time with the railroad.

In addition, all the Q’s streamline-era passenger cars bore both numbers, as was standard, and formal names. Only one prefix was used, for all types; you probably won’t be surprised to know that word was “Silver.” The general public probably associated the word “Zephyr” with the railroad most closely, but where the metal met the rail, the shiny Budd streamliners prevailed exclusively.

In truth, you couldn’t have a Burlington intercity passenger train in the postwar era without both cars that were both silver and named for the shiny metal. In the mid-1960s, the railroad acquired some smooth-side coaches from the Chicago & North Western that were Pullman-Standard products; they were painted silver, but didn’t carry names of any sort (which probably relieved someone in the Burlington’s passenger department of the task of forming even more two-part word association exercises beginning with “silver”).

Finally, while relatively late to the game, Canadian Pacific’s monumental 1955 order to streamline its transcontinental passenger service with Budd products has proven to be the last stalwart, carrying on to this day under the VIA Rail banner. These cars are the sole survivors of the Budd postwar stainless-steel car extravaganza still performing a service with any resemblance to their original purpose.

The paint on their letterboards morphed from the initial maroon to “Action Red” while still at CP; following VIA’s takeover of Canadian intercity passenger services, this became blue. And keeping the Budd/stainless tradition in mind, it was only natural that VIA chose to market this for several years as “Silver and Blue” service.

Mr. Horner, thank you so much. I have been searching for this for years, without success. Trains September 1997, page 47, bingo!

Happy to help and glad you found what you were looking for!

The Budd set delivered to the Boston & Maine was initially named the “Flying Yankee” on its initial run between Boston and Bangor, Maine, with a stop at Portland. It ran under several names over the years. The “Minuteman” was a Boston to Troy, New York train, and was sometimes covered by the Budd trainset in its later years.

The Milwaukee Road was using orange and maroon on passenger cars well before the streamliner era.

Question: Can anyone at Trains or a reader tell me the issue of the Trains Magazine containing the article detailing the record-breaking run of the Denver Zephyr? Thanks in advance! Al

https://www.rrmagazineindex.org/?q=Denver+Zephyr+record-breaking&sy=0&ey=0&m%5B%5D=TRN&p=1

The link above should contain links to the copies of Trains Magazine that contain the phrase “Denver Zephyr record breaking.” There are a few issues in there from across the decades, but one of them should be the issue you’re looking for!

Budd is a dying breed. All the railroads keep them in their heritage fleets and repaint them. Most of the old Budds are either rotting away in Florida or sitting in the boneyard in Beach Grove but they are being rebuilt. RRHMA and Union Pacific take old Budds coaches and give them a new life. Half the fleet was restored and some are back in service. I wish RRHMA luck this year restoring the dinner let’s get this back in service.

The Pullman Company couldn’t build the ribbed sided cars as Budd did for patent reasons, but did produce smooth sided cars for the New Haven in their ex-Osgood Bradley plant in Worcester by attaching ribbed sidings to the smooth sides of the carsl. Water eventually seeped between the car bodies and panels and ended up causing corrosion of the car body.

As a footnote, Amtrak ended the rainbow period by repainting its colorfully painted cars in a silver/gray color called Platinum Mist in an attempt to have these cars come close to matching their stainless equipment.