First of two parts

LANDQUART, Switzerland — A railroad’s shops can tell you a lot about the company in general. That was certainly the case from a visit to the main shops of the meter-gauge Rhätische Bahn, which firmly keeps one foot in the past while also embracing cutting-edge technology.

My host for this tour — as for much of my visit to the railroad — was Markus Zaugg, the railroad’s head of rolling stock. Zaugg was an ideal host — he has clear enthusiasm for his job and a personality that makes him a pleasure to be around (he seems to know and be interested in everyone on the railroad, which has about 1,700 employees). And he speaks terrific English, having spent several years in San Francisco when he worked for Swissair before joining the RhB. (He even became a baseball fan while there; during one of our meetings, he was wearing a San Francisco Giants jacket.)

The shop complex features separate shops for the railroad’s diesel and electric equipment, car shops, a landmark roundhouse that dates to 1890, and a building, not quite finished at the time of my visit, built specifically to maintain the four-unit Capricorn EMU trainsets that are now the backbone of passenger operations.

It may be a surprise that the railroad has a diesel shop, given that it is fully electrified. But it has a variety of diesel-powered equipment — maintenance vehicles, snowplows, even refrigerated containers with diesel generators. The railroad’s few diesel switchers are on their way out; the government will no longer provide funding for them, and the railroad is almost entirely owned by the canton and federal governments.

One of the more interesting pieces of diesel equipment on hand during this visit was one of the two pieces of emergency firefighting equipment for the 19.2-kilometer Vereina tunnel, which we would visit later in the week. These are designed to be operated by firefighters, not railroaders, with controls that are both simplified and and oversized (with extra-large on-off buttons, for example) that can be used when those firefighters are in full gear including large, heavy gloves.

Zaugg leads me to a project he had mentioned before the tour began: restoration of the railroad’s first locomotive, a steam engine built in 1889. At this point, it simply a bare frame — something less than awe-inspiring, I confessed.

“Yes, but we still have it,” he said. “And most of the parts are still original.”

The complete reconstruction of the locomotive will include a new boiler being fabricated in England. Not long after my visit, the frame was slated to be sent to England to be mated with the boiler, after which they were to be returned to Landquart for work to continue. The restoration is expected to take another two years.

“At the moment, we have only one person that can work full time on it,” Zaugg said. Eventually, he said, the locomotive will return to operation in its original color scheme. “It changed color about four or five times during its lifespan,” he says. “We are painting it the original color: all black with chrome lining here under the tape. And then there will be red lining over the cab house. It will be beautiful.”

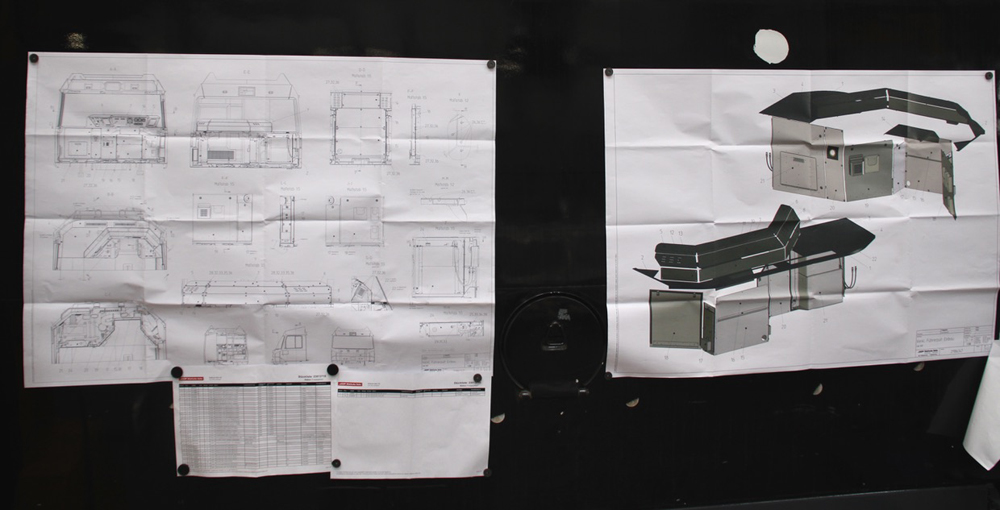

Moving into the main shop, we arrive at a largely disassembled electric locomotive, a sister unit to the railway’s dozen Ge 4/4 III units built by SLM/ ABB and Adtranz between 1993 and 1999. Those are the newest and most powerful of the railroad’s road units, rated at 3,100 kilowatts (4,160 hp). This, it turns out, is a major project that speaks to the capabilities of the shop staff.

“We need more of them … but the industry won’t build us that type of locomotive any more, or just for ridiculous prices,” Zaugg says. “So we are going to other railways in Switzerland and bought their locomotives they don’t need any more. We bought this one from the MOB, but their electrical installation is 180 degrees different from us.” [The Montreux Oberland Bernois Railway runs between Montreux and Zweisimmen — see “MOB mentality,” Trains Magazine, May 2024 — but as one of the country’s earliest electrified railways, it uses a 900-volt DC power system. The RhB operates with 11,000-volt AC, except for the Bernina Line, which is 1,000-volt DC.]

“So basically, all that we can use from that is the shell. Everything else, we build new from scratch,” Zaugg says. “So basically, we build our own locomotive. This is a very ambitious project, and we underestimated quite a lot. It should have been finished last year; it’s still going on, but the result will be great. We are very proud that we are even capable of doing such a thing, that we have the know-how inside the company to do such a thing.”

The project is both a pilot for future rebuilds of the 12 RhB Ge 4/4 III locomotives, and additional purchase-and-rebuild work. “We have the opportunity from another railway in Switzerland to buy two others of these locomotives.” (Those will also require modification, since MBC, or Morges-Bière-Cossonay Transport, also uses a different power source, 15,000-volt AC.)

From the shop building, we emerge into a storage yard mostly full of retired locomotives and rolling stock. Many of these are items Zaugg would like to add to the railway’s already sizable collection of historical equipment, but he is constrained by a lack of storage space that is about to get worse: this yard is about to be reclaimed by the town of Landquart for community use.

“All the cars or vehicles that are standing here, it’s undecided what will happen to them,” he says. “They may become [part of the RhB historic fleet], or they may be sold to a museum, or whatever.” He pauses, then adds reluctantly, “Or they’ll go for scrap.”

We walk to a building on the edge of the shop complex. As Zaugg unlocks the door, he explains it houses the parts supply for much of the heritage equipment (and so is kept locked because some of the items inside would have considerable value to collectors). It is filled with wheelsets from older locomotives, parts for steam locomotive No. 1, and various other spares.

The building offers its own history of the development of Swiss rail technology. Take, for example, traction motors. He points out a modern version — “quite small,” he says — then points out one that is considerably larger, from one of the historic crocodile units, which he says has only half the horsepower. Finally, he points to a much larger object nearby. “The first traction motor on the Rhaetian Railway,” he says. “It is about two meters diameter and [just] 300 horsepower. It’s quite interesting to see the development.”

We pass through one building where a bright yellow car undergoing restoration. The color indicates that it is from the Bernina Line, which began as a separate railroad before being absorbed into the RhB. Elsewhere in this building are driving wheels for a steam locomotive; Zaugg notes that the company does contract work for museums and tourist railroads that don’t have sufficient shop capability to perform the tasks themselves.

The main car shop includes a large number of the red cars still in use on some RhB trains, although the Capricorn EMUs have assumed the primary role.

“These cars will be replaced in the next five to 10 years, because they were were built in the ’70s and have no air conditioning, no nothing,” he says. “No plugs for putting your phone in. … They’re still good, but it’s not the standard that the people expect any more.” [One thing these cars have that their modern counterparts mostly lack: windows that open. For photographers, their retirement will be a loss.]

The next stop in our tour: the roundhouse that Zaugg suggests is “probably the most famous railway spot in the whole of Switzerland.” But we’ll get to that in Part 2.

Part two of this article will appear Tuesday, April 22.