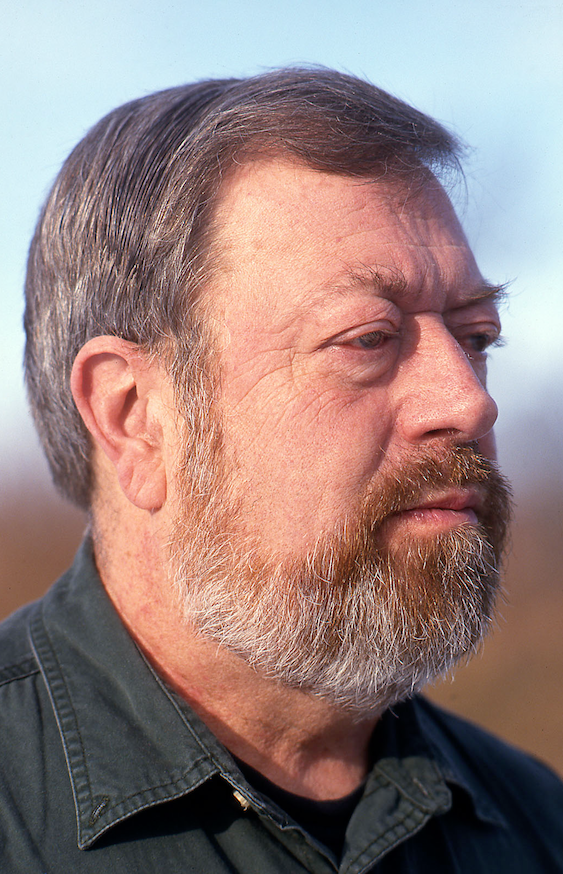

Jim Shaughnessy died Aug. 7 at age 84 after a long illness. He was one of the last of the “steam era” photographers, and as former Trains editor Kevin Keefe said in a tribute, “He was an important figure in the shift away from simple train pictures toward depictions of the entire railroad environment.” His innovative photography was so distinct that you could see one of his photos and immediately know it was taken by him before even seeing the credit line.

Living in upstate New York, his “home” railroad was Delaware & Hudson, a railroad he kept shooting from the 1950s right into its assimilation into Canadian Pacific. He wrote the definitive story of D&H in his book Delaware & Hudson, and also wrote the story of another New England favorite with his 1964 book The Rutland Road.

Like Richard Steinheimer and Phillip Hastings, Shaughnessy was a practitioner of night photography in a time when many photographers put their cameras to bed at night. His bold night images of subjects as varied as Canadian branch line steam to Union Pacific Big Boys frequently left readers of Trains Magazine in awe.

While he captured the transition from steam to diesel in the 1950s, unlike many steam fans Shaughnessy didn’t put his cameras away as steam retired. He kept right on shooting into the 21st century, continued to write books – his last was Jim Shaughnessy: Essential Witness published in 2017 – and wrote a column for Classic Trains magazine called “The Shaughnessy Files” which showcased both his photos and memories of his photographic adventures.

In the late 1950s, while Shaughnessy was making waves with his groundbreaking images, another photographer arrived on the scene who would shake up rail photography for good. His name was John Gruber, and his new approach to rail photography left a lasting impression. Like Shaughnessy, he eschewed the 50-millimeter lens and three-quarter “wedgie” approach to rail photography. In the early 1960s he mastered the use of the telephoto lens, which was heresy as far as some photographers were concerned.

But the die was cast: with that issue it could be argued Trains transitioned from the steam to the diesel era. It forced readers to accept the reality of the diesel and brought in new readers who would sustain the magazine through the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Yet Gruber is also remembered for his images of steam survivors such as Minnesota’s Duluth & Northeastern, the Rio Grande narrow gauge, and Southern Railway excursion star No. 4501, with Gruber teaming with Morgan on the book Locomotive 4501.

Like Shaughnessy, Gruber got close to the railroaders themselves, documenting them at work when most photographers were engrossed by railroad equipment. Look at a Gruber photograph and inevitably it includes the people that kept the railroad running.

Gruber edited the magazine Vintage Rails, wrote books, and in 1997 founded the Center for Railroad Photography & Art, based in Madison, Wis. and today a thriving organization known for its growing archives, publications, exhibits and symposiums. Both Gruber’s and Shaughnessy’s collections will go to the Center. Executive Director Scott Lothes said it expects to take delivery of the Shaughnessy collection in the spring and is working with Gruber’s family on his collection.

“We deeply mourn both men’s passing, and all of us at the Center are looking forward to preserving their work and making it available to wide audiences,” Lothes said. So, the work of these two innovative practitioners of the art of railroad photography will continue to be seen in the years to come.

The loss of these two giants of railroad photography and what they left in their wake makes it No. 10 on Trains editors’ Top 10 list for 2018.