However, 30 years ago passenger trains in the United States were almost finished.

Declines in passenger train ridership can be traced back to the 1930s, when the automobile began its formidable challenge to the new streamliners introduced by the railroads. The rise of commercial aviation in the 1950s took significant numbers of long-distance travelers away from passenger trains, while burgeoning highway systems, subsidized at the municipal, state, and federal levels attracted short-distance travelers.

But the final blow came in October 1967, when the U.S. Postal Service cancelled its lucrative first-class mail contracts with the railroads in favor of trucks and airplanes. (Second- and third-class mail continued to be hauled on long-distance passenger trains.)

One by one, trains that had survived the onslaught of highway and air competition began to disappear.

From Railpax to Amtrak

After much effort the NARP lobbying worked, and from that success came the Railroad Passenger Service Act (Railpax), which Congress passed on October 14, 1970. On October 30, 1970, President Nixon signed Public Law 91-518, and the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC) was created.

All railroads that operated passenger trains when the new law was signed had until May 1, 1971 to become members of the NRPC, or continue to run their own passenger trains. The NRPC membership price was either cash, or passenger equipment/services based on half the road’s passenger losses for the last full year of operation (1970), or purchase of common stock in the new company. The biggest advantage to joining NRPC was of course, relief from the financial burden of maintaining passenger service.

Most railroads joined, although four opted out and continued to operate passenger trains on their own: Southern, Rio Grande, Rock Island, and Georgia Railroad.

Denver & Rio Grande Western operated the tri-weekly domeliner Rio Grande Zephyr between Denver and Salt Lake City until April 25, 1983. (After Rio Grande cancelled the service, Amtrak shifted its own Chicago-Oakland San Francisco Zephyr from Union Pacific’s line across Wyoming and Utah to the Rio Grande route, and changed the train’s name to the California Zephyr.)

Rock Island operated two pairs of intercity passenger trains, one between Chicago and Rock Island, and one between Chicago and Peoria. The service lasted until January 1, 1979.

The Georgia Railroad ran four pairs of mixed trains: Atlanta-Augusta (formerly the Georgia Cannonball), Camak-Macon, Union Point-Athens, and Barnett-Washington. The last mixed train ran on May 6, 1983, operated by Georgia Railroad’s successor Seaboard System.

The original Amtrak planners included eight Presidential appointees, and select members from the Federal Railroad Administration and Department of Transportation, led by Secretary John Volpe.

The group was charged with setting up a nationwide passenger railroad system that would take over operation of all intercity passenger trains. Amtrak’s planners managed to achieve something the freight railroads would not have until 1980: freedom from regulation. The Interstate Commerce Commission had no say over how Amtrak was formed and how it was to operate.

The group established a system of 21 key routes, or “city pairs” that formed Amtrak’s initial nationwide passenger network:

- Boston to New York

- New York to Washington

- New York to Buffalo

- New York to Chicago

- New York to Kansas City via St. Louis

- New York to Miami (and Tampa/St. Petersburg)

- New York to New Orleans

- Washington to Chicago

- Washington to St. Louis

- Norkfolk/Newport News to Cincinnati

- Detroit to Chicago

- Chicago to St. Louis

- Chicago to Cincinnati

- Chicago to Miami (and Tampa/St. Petersburg)

- Chicago to New Orleans

- Chicago to Houston

- Chicago to Seattle

- Chicago to San Francisco/Oakland

- Chicago to Los Angeles

- New Orleans to Los Angeles

- Seattle to San Diego

Rail service was divided into short-haul and long-haul categories. Short-haul trains would run 300 miles or less between intercity terminals; long-haul trains covered distances greater than 300-miles. Both long-haul and short-haul city endpoints had to have a population base of at least one million.

One determining factor used for establishing the short-haul routes was the existing rail and roadbed between city pairs, which had to be of sufficient quality to allow operation of passenger trains without additional capital improvements.

The planners established which trains were to be operated, frequency of operation, train connections, and through car service between city pairs. In addition, it was decided which trains would have sleeping and dining car services, and lounge and parlor car services. Train names and numbers were also assigned.

The advertising firm of Lippencott & Marguiles created the name for the new passenger carrier, AMTRAK (American Travel by Track), and developed the corporate colors of red, white and blue and the well-known Amtrak inverted arrow logo. Amtrak’s arrow logo was replaced in 2000 with its wave-like “travel mark” introduced concurrent with the launch of its satisfaction guarantee program, and in anticipation of the inauguration of the high-speed Acela Express.

Amtrak’s first days

For passenger train lovers, May 1, 1971 was a day of reckoning, as Amtrak began its first day of operation, and many privately operated long-distance trains made their final arrivals. The first day saw 184 Amtrak trains running on a 23,000-mile network that served 314 communities.

Sadly, this was half the amount of some 440 passenger trains that had run the day before. Even factoring in the 34 additional trains still privately run by freight railroads after May 1, the loss of service was staggering, and many large cities and small towns suddenly had no passenger service at all.

To see a complete list of passenger trains running just prior to, and just after, Amtrak’s takeover, open the following PDF document. (If you need to Adobe Acrobat, a free download is available at the bottom of this page.

Overnight, all passenger trains on the Baltimore & Ohio, Central of Georgia, Chicago & North Western, Delaware & Hudson, Grand Trunk Western, Norfolk & Western, and Northwestern Pacific disappeared.

Discontinued trains on other railroads Chesapeake & Ohio’s Pere Marquette (Chicago-Grand Rapids-Detroit), Milwaukee Road’s storied Hiawatha trains (Chicago-Twin Cities), and Louisville & Nashville’s Pan-American (Cincinnati-New Orleans) and Georgian (Atlanta-St. Louis).

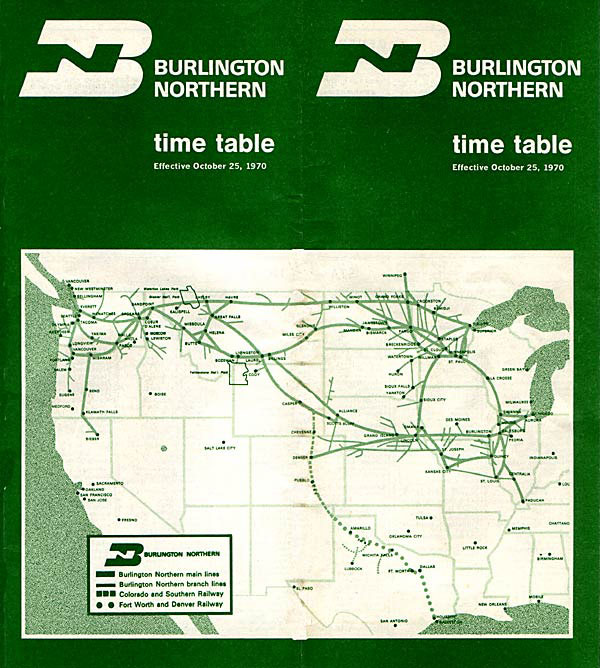

Santa Fe’s San Francisco Chief (Chicago-Oakland) was discontinued, as were Burlington Northern’s Western Star and Mainstreeter (St. Paul-Seattle).

In the East, many Penn Central Boston-New York-Washington trains continued to run on the Northeast Corridor. At start-up, the Broadway Limited was Amtrak’s only New York-Chicago train (with a connection serving Washington, D.C.), and in 1972 was the first Amtrak train to receive the new red-white-blue colors. Amtrak discontinued the Broadway Limited in 1995.

For a list of trains operated by Amtrak on May 1, 1971, read “Amtrak trains on May 1, 1971” found at the bottom of this page.

From the start, the new carrier was also plagued with equipment incompatibility, train crew and operation problems, and passenger complaints.

One major problem the railroad faced was with the equipment pool, which numbered nearly 300 locomotives and 1200 cars.

Amtrak began operations by leasing motive power and rolling stock supplied by the freight railroads. In the East, most of the railroads had operated older, dilapidated coaches and sleepers, while western railroads had invested heavily in new dome cars and coaches. When this equipment was put together, many inconsistencies arose. For example, the eastern repair shops were unfamiliar with maintenance procedures on the western cars, even though most cars were built either by Pullman-Standard or Budd.

The “Rainbow Era” was short-lived, and by 1974 the new color scheme was painted on most Amtrak equipment. Newly purchased locomotives and rolling stock began appearing, too – SDP40Fs from EMD in 1972, French-built Turboliner trainsets in 1973, and new Amfleet coaches from the Budd Company in 1975.

First-year growth

Amtrak’s network of trains grew as well, and some of the cities and towns that had been without service on May 1, 1971, later became part of the Amtrak system.

The first new train added was an overnight New York-Buffalo-Cleveland-Chicago train (later known as the Lake Shore Limited), introduced on May 10 – a mere ten days after Amtrak’s first day – subsidized by the states of New York and Ohio. (The Lake Shore Limited was discontinued in January 1972, but revived by Amtrak in October 1975.) This train was made possible because of the 403(b) provision in the Amtrak act.

403(b) stipulated that states could introduce new Amtrak service by picking up a percentage of the losses incurred with such service. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts pitched in for Boston-New York train service on the Inland Route by way of Worcester, Springfield, and Hartford, inaugurated May 17. The state of Illinois subsidized the Chicago-West Quincy Illinois Zephyr, begun November 14.

Connections between the Chicago-Cincinnati James Whitcomb Riley and the Cincinnati-Washington/Newport News George Washington were improved on July 1, 1971, when the two trains were combined to operate as through trains. A new train, the West Virginian, was added September 7, 1971, running between Washington, D.C., and Parkersburg, W.V.

With the November 14, 1971 schedule, more train service was added in existing corridors (Boston-Washington, New York-Washington, Chicago-Minneapolis-St Paul, and Los Angeles-San Diego), and two daily trains began running through Chicago between Milwaukee and St. Louis.

Amtrak also reduced service to New York’s Grand Central Terminal in November 1971, eliminating its Grand Central-New Haven trains, in order to provide connections for Washington-New York-Boston passengers by consolidating all Northeast Corridor service at Pennsylvania Station. Amtrak would continue to use Grand Central Terminal for its Empire Service trains to Albany and Buffalo until April 7, 1991, when the $89 million West Side Line opened, providing a direct rail link to Penn Station.

New York wasn’t the only city where Amtrak trains operated from two terminals.

In Philadelphia, Amtrak’s Keystone trains from Harrisburg used the upper level of two-level 30th Street Station, then continued east across the Schuylkill River to terminate at the underground ex-Pennsylvania Railroad Suburban Station (Penn Center) in Center City. That practice lasted until May 15, 1988, when Keystone trains joined the rest of Amtrak’s trains on the lower level, leaving the upper level to be used strictly by SEPTA commuter trains.

While most Amtrak trains serving Chicago used Union Station, four trains, the City of New Orleans to New Orleans, South Wind to Miami, James Whitcomb Riley/George Washington to Cincinnati, Washington, and New York, and Shawnee to Carbondale initially operated from Central Station, the former Illinois Central Railroad passenger terminal. Within a year, Amtrak consolidated all its operations at Union Station. The last Amtrak train departed Central Station on March 6, 1972.

Since that tentative first year, service has improved dramatically, and new locomotives and rolling stock have replaced the hand-me-down equipment of 1971. Although the number of trains operated by Amtrak has grown over time, schedules and frequencies continue to fluctuate, subject to the railroad’s always-precarious financial position. Today, the number of cities and towns with Amtrak service exceeds 500.