The earliest locomotives in North America – 0-4-0s based on English designs – had suspension systems that were too rigid, and they tracked poorly.

The first American locomotive capable of handling the undulating track was the 4-2-0, which had a three-point suspension system. The swiveling pivot point of the lead four-wheel engine truck was one of the suspension points. Each of the two driving wheels acted as another suspension point. So, in the same way a three-legged stool will always be stable on irregular ground, the 4-2-0 could be stable on irregular track.

The 4-2-0 quickly grew into the 4-4-0, with the extra pair of driving wheels added to provide greater adhesion. Henry R. Campbell, chief engineer of the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad designed and built the first 4-4-0 in 1837.

The 4-4-0 retained its forerunner’s three-point suspension system. This was accomplished with an equalization system that linked together the two driving wheels on each side of the engine. If, for example, the right front driver dropped down because of a dip in the track, some of the weight it supported would be transferred to the right rear driver. Thus the two driving wheels on each side – together – provided the equivalent of one suspension point.

The three-point suspension system became a fundamental part of American locomotive design and virtually all locomotives from the 4-4-0 to the 4-8-8-4 employed some form of it.

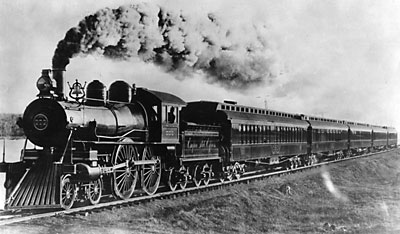

As train lengths and speed increased, the 4-4-0 also grew, with the addition of bigger cylinders, a larger boiler, and a bigger firebox. The 4-4-0 was a well-balanced design with natural proportions. (In other words, the size of the boiler, grate area, firebox, and cylinders were closely matched to its service requirements.) In short, it was hard to build a bad one.

The widespread application of air brakes in the 1880s spelled the end of the 4-4-0. Air brakes made it possible to run longer and heavier trains, and that in turn created a demand for bigger locomotives. Freights that once could have been handled by 4-4-0s soon needed 2-6-0s and 2-8-0s. Passenger trains were put in the charge of 4-6-0s and 4-4-2s.

Once heavier power appeared, major railroads consigned the 4-4-0 to light passenger jobs, often on branch lines, although some short lines continued to use it in freight service.

After 1900 few new 4-4-0s were built, with the very last going to the Chicago & Illinois Midland in 1928. Along with two other Americans received the prior year, the engine was used on a couple of local passenger runs.

By this time, over 25,000 Americans had been built. The 4-4-0 lasted into the diesel era and some examples ran into the late 1950s. Many still exist today in museums and on tourist railroads.