History of the New York, Ontario & Western

The New York, Ontario & Western Railway struggled to find its place among the many transportation systems serving New York City, but in the end it was able only to secure a place in history as the first Class I railroad to be abandoned in entirety. Despite this unenviable status, “the O&W,” as it was known, did endear itself to the communities along its line. After all, it was the carrier that had brought boxcars full of prosperity to every community along the line during its 76-year life.

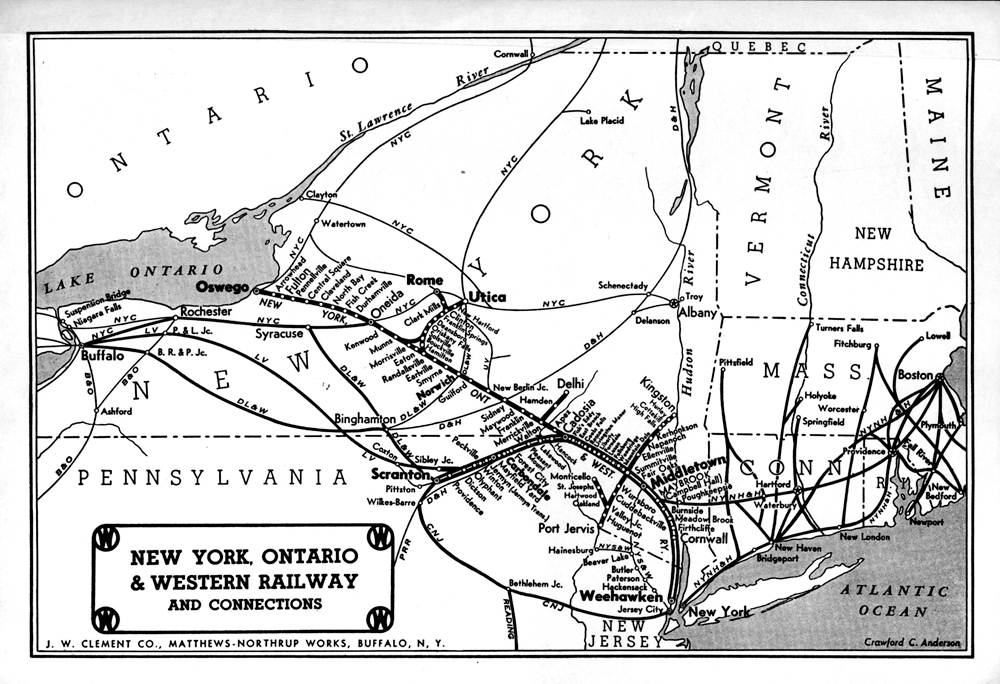

Begun on January 21, 1880, the O&W set a goal of improving the Oswego–New York corridor, as well as the branches to New Berlin, Delhi, and Ellenville, N.Y., it had inherited from the New York & Oswego Midland. The O&W developed a new entrance to Gotham from Middletown, N.Y., that ran to Cornwall on the Hudson River, thence to Weehawken, N.J., by rights on the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railway (later New York Central).

O&W extends its reach

In 1886, the O&W leased the operation of the Utica, Clinton & Binghamton and the Rome & Clinton railroads from the Delaware & Hudson Canal Co., and built a new line to Sylvan Beach on Oneida Lake. By acquiring the UC&B and R&C, the O&W extended its operation into new market areas, and the Sylvan Beach Loop (as it became known) became a seasonally important corridor for transportation to central New York’s recreational mecca. Three years later, the O&W added two new branches: the Wharton Valley Railway from New Berlin to Edmeston, and the Port Jervis, Monticello & Summitville, which connected its three namesake communities.

A more significant addition occurred in 1890 when the O&W orchestrated the building of a 54-mile branch from Cadosia, N.Y., to Scranton, Pa., to tap the coal reserves in Pennsylvania’s Lackawanna Valley. Revenue from this Scranton Division would produce a robust financial condition that gave O&W the means, and the need, to pursue further line improvements.

Because of the railroad’s emergence as a coal-hauler, the Lake Ontario harbor piers at Oswego, N.Y., were improved, and coal delivery trestles at Cornwall and Weehawken were built. A water-borne fleet was also built up to enhance operations in New York Harbor, as well as northeastern seaboard and Great Lakes destinations.

I. W. King, Joel King collection

Tunnels, bridges, modern power

Further, owing to the onslaught of heavy coal trains, O&W prosecuted the excavation for its fourth tunnel (under Northfield Mountain) to eliminate a mainline switchback (the other three tunnels were at Cadosia, South Fallsburg, and Bloomingburg). Five years after the tunnel went into service in 1891, the opening of the Pecksport Connecting Railway provided an alternate route for freight trains that previously had to assault the heavy grade at Eaton on the Northern Division.

The heavier trains and locomotives forced O&W to strengthen all its bridges. It also built several new ones, including the 820-foot long, 165-foot high structure over Lyon Brook to replace a spindly Midland span. Beginning in 1902 (the same year the branch to Ellenville was extended to Kingston), the O&W set about double-tracking its Scranton Division and its Southern Division south of Cadosia.

This project was finished in sections over the next nine years, and upon its completion, the O&W had reached its most modern and efficient form. The only other major route change would occur in 1928 when 3 miles of new mainline track were laid to eliminate 21 grade crossings in Fulton.

As it improved its physical characteristics, the O&W also acquired modern motive power to haul its numerous coal, milk, passenger, and general freight trains. Where previously Camelback 4-4-0s, 2-6-0s, and 2-8-0s were as common as the road’s wooden coaches and country depots, a corps of end-cab locomotives helped usher in the new era. E-class Ten-Wheelers (1911), W-class Consolidations (1910-11), X-class 2-10-2 “Bull Mooses” (1915), and Y-class Mountains (1922 and ’29) provided the power for passenger trains to the Catskills, milk trains to Gotham, and coal trains to Oswego, Cornwall, and Weehawken. Still, many Camelbacks worked into the mid-1940s.

O&W’s glory years of coal and milk

The first two decades of the 20th century were O&W’s glory years. Business was good, the road was in fine shape, and nothing but black ink was in the ledger books. The chief contributors were coal and milk, and for both, the road had itself to thank. After all, it built the Scranton Division, and although the O&W never handled more than 6 percent of the anthracite hauled out of the Lackawanna Valley, coal revenue fueled the O&W’s modernization.

Likewise with the milk trade. O&W had initiated a systematic building of milk stations, creameries, and ice houses, and those gathering points — as well as those of independent companies — were located all along the line to Oswego. The 40-quart milk cans, and later bulk tank cars, moving from upstate New York sites, propelled O&W into becoming one of the largest suppliers of milk to New York’s metropolis. In 1902-03, the O&W led all other railroads in supplying milk to Gotham.

As the O&W rolled through the 1920s, its good years were back in the caboose while the locomotive was heading straight into the Great Depression. Besides its saw-tooth profile that did not lend itself to operating economy, the O&W suffered from competition at all its important terminals. Its main competitor was the New York Central, so O&W felt relieved when the New Haven Railroad gained a controlling interest, rather than its arch competitor.

The Depression exacerbated the O&W’s operating difficulties. Laced with six mainline bidirectional pusher districts, plus one on the Scranton Division, single-track tunnels in otherwise double-track territory, and declining revenues from coal, milk, and passengers, the O&W was ill-prepared for the worst economic upheaval in America’s history.

These traditional revenue sources collapsed during the 1930s, forcing the O&W to close depots and signal towers, reduce its workforce, and pull up second main track. Short sections of the Southern Division had CTC signaling installed. Bridge traffic was developed to link the Lehigh Valley and Lackawanna railroads at Scranton with the New Haven at Maybrook, N.Y. Northern Division passenger trains had been dropped in 1929.

Robert F. Collins

Bankruptcy, diesels, and decline

Despite all this, NYO&W still had to petition for bankruptcy protection, entering receivership in 1937. O&W’s trustee, Frederick E. Lyford, pared the physical plant and operations to the bone. Property was sold, wage concessions were requested and received from the unions, and the stations at Norwich, Oneida, and Oswego were sold. In 1940 the New Berlin branch was sold to the Unadilla Valley Railway.

Dieselization was hoped to be a savior, and under Lyford’s direction a handful of GE 44-ton switchers arrived in 1941. Nine two-unit EMD FTs came in 1945 and were put into fast merchandise service between Scranton and Maybrook, and Scranton and Norwich. Lyford’s successors in 1948 acquired additional F3 and NW2 diesels, enough to banish steam locomotives from service by that summer.

By that time, though, O&W’s accumulated losses amounted to $38 million. It was beyond the ability of trustees, the reorganization court, and diesel locomotives to extricate the carrier from financial ruin. Nevertheless, passenger trains from Weehawken to Walton (then only to Roscoe) kept running until mail contracts gave out in 1950; the service was suspended in September 1953. Although milk and coal trains were a memory, gray-yellow-and-orange diesel locomotives soldiered on, leading a dwindling number of ever-shorter freight trains.

By the mid-1950s, the reorganization court — which had been searching for a buyer for the road now truly earning another of its nicknames, the “Old & Weary” — was advocating total abandonment. Additionally, the U.S. government was suing for taxes and retirement payments that were in arrears, and New York state began planning on how best to use the O&W right of way for highway improvements.

End of the line

On March 29, 1957, the O&W finally reached the end of the line. A final telegraphic train order was sent out to Norwich allowing Extra 805 South to run to Middletown, the railroad’s operating headquarters, on that date. When it arrived, the sounds of O&W railroading ceased.

The O&W did not live to see another day. It was scrapped the following year, and its surviving buildings and property sold to satisfy liens, mortgages, and stockholders. Portions of the line were acquired by the NYC (Fulton–Oswego), Lackawanna (Utica–New Hartford and Norwich), and Erie (Middletown). Surprisingly, these sections still see sporadic service today, though under more modern banners.