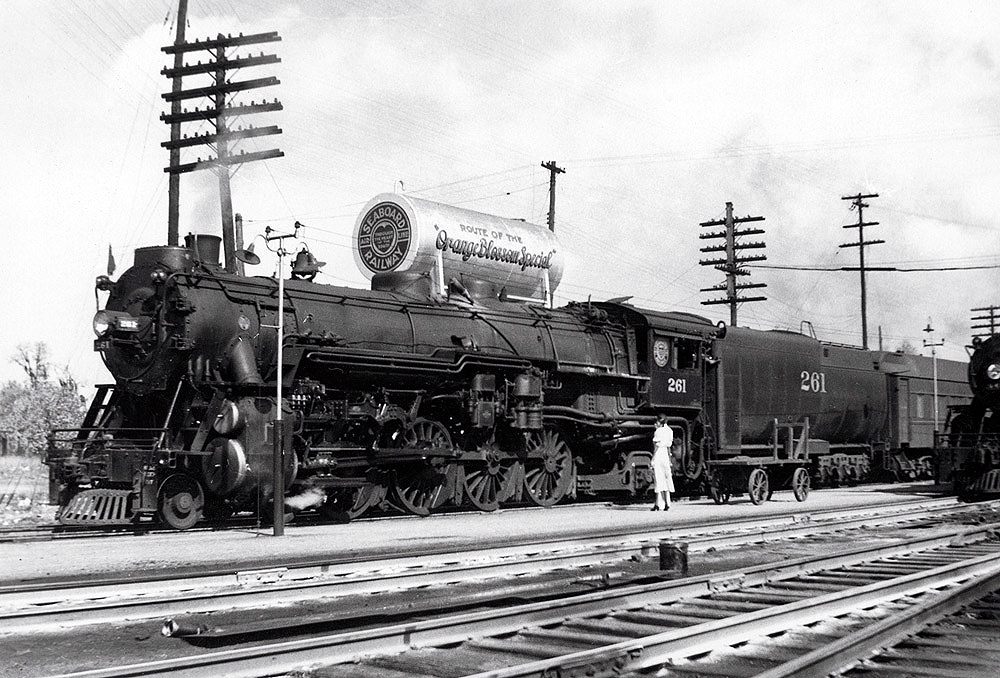

Jim McClellan photograph

History of the Seaboard Air Line

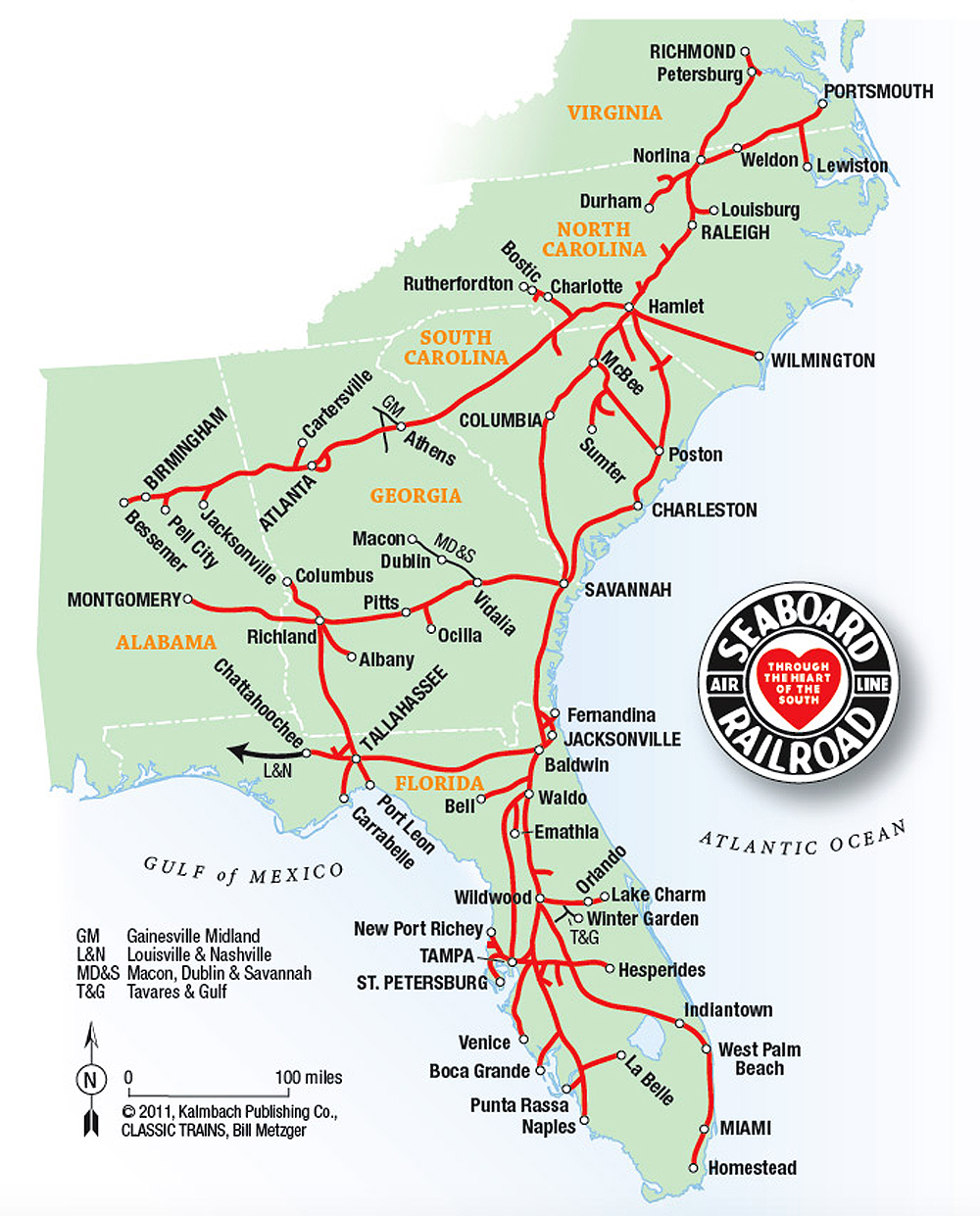

The Seaboard’s beginnings date to 1832, when the Portsmouth & Roanoke was chartered to build from Portsmouth, Va., to Weldon, N.C. Opened in 1834 the companies’ backers saw great potential to link the North with the South’s agricultural and forest products and with its developing potential for industry. P&R became the Seaboard & Roanoke, which began acquiring other lines and building trackage further into the Carolinas. The S&R and its associated roads began calling themselves the Seaboard Air Line system, and by 1895 had reached Atlanta.

The “Air Line” name was often used by railroads of the period to denote a route supposedly “as straight as the crow flies.” It was a reasonably direct run from Portsmouth to Weldon, but the Air Line label would be more than hype when in the 1880s Seaboard acquired a line linking Hamlet and Wilmington, N.C., which included a 79-mile tangent track, longest in the U.S.

As the 19th century closed, the SAL system came under control of a group led by John Skelton Williams, who added a line from Richmond, Va., to Weldon, and acquired the Florida Central & Peninsular, transforming what had been a Portsmouth–Atlanta carrier into a north-south line. In 1900, the various SAL roads were incorporated as Seaboard Air Line Railway with its coastal main line from Richmond going through Raleigh, Columbia, and Savannah to Jacksonville and Tampa.

Building the system

Other important lines ran from Monroe to Rutherfordton, N.C.; from Savannah west to Montgomery, Ala.; and from Jacksonville to Chattahoochee, Fla., and a connection with Louisville & Nashville on to Mobile, Ala., and New Orleans. The early route map was completed by branches in the Carolinas and Florida. The Atlanta line extended to Birmingham, Ala., in 1904, adding traffic and securing its place as second-busiest after the north-south main.

Seaboard emphasized passenger service from its earliest days. As soon as SAL expanded to Florida, it promoted travel there via such trains as the Florida-Cuba Special and the seasonal Seaboard Florida Limited, both forwarded to Miami over the Florida East Coast. Early freights often carried produce from Florida as well as phosphate rock mined from the “Bone Valley” area near Tampa.

G. W. Pettingill photograph

Further expansion

SAL continued to expand, in 1917 adding a low-grade freight line between Hamlet and Savannah via Charleston, S.C. A fresh burst of construction and acquisitions in the 1920s added mileage, notably through south-central Florida to Miami in 1927. In 1925, SAL leased the Charlotte Harbor & Northern. In 1928, Seaboard acquired the Georgia, Florida & Alabama, opening a shortcut from Florida to the Montgomery line to speed freight to the Midwest. SAL also controlled short lines including the 92-mile Macon, Dublin & Savannah in Georgia and the 35-mile Tavares & Gulf in Florida.

The Miami extension was accompanied by inauguration of the Orange Blossom Special, an all-Pullman, winter-only luxury flyer that soon gained national fame. Seaboard spared no expense in publicizing the elegant train, advertising it on boxcars, and the Blossom even had a popular bluegrass song written about it in the late 1930s. The Blossom was a fitting symbol of Seaboard’s early fortunes, but the good times didn’t last. The debt load from the decade’s enthusiastic expansion couldn’t withstand the collapse of the Florida boom and the onset of the Great Depression, and SAL was forced into bankruptcy in 1930.

Although the 1930s were lean times, SAL’s receivers made investments to bring back business. The railroad’s interest in streamlining and diesels led to semi-streamlined rail motor cars and semi-lightweight “American Flyer” coaches in the mid-1930s and to Electro-Motive E4 diesels for the Orange Blossom Special in 1938. Seaboard later unveiled a new lightweight streamliner, the seven-car New York–Miami Silver Meteor. SAL quickly went back to EMD and Budd for more equipment and by 1941, the railroad was daily running 14-car trains to Miami and Tampa.

Wartime strain, postwar glow

While the World War II years strained SAL’s resources the railroad shouldered the load with new EMD FTs, secondhand steam engines from Western Maryland and Chicago & North Western, and installation of block signals and centralized traffic control over large portions of its main line. Wartime income helped the carrier emerge from receivership in 1946 as Seaboard Air Line Railroad.

High-profile wrecks, several involving passenger trains, spurred quick postwar completion of the signaling and modernization campaign. SAL’s earliest CTC installation had started south from Richmond in 1941. By the early 1950s, signals covered most mainline mileage, keeping the operation competitive with its double-tracked neighbor Atlantic Coast Line.

Seaboard added more streamlined cars from Budd in 1947 and lightweight sleepers from several builders beginning in 1949. The Silver Star name was given to what had been a second section of the Meteor, and the two “Silver Fleet” members held down the first-class New York–Florida trade. The Silver Comet was added to the New York–Birmingham route. Seaboard continued to maintain its premier trains to high standards into the 1960s, proudly calling itself “The Route of Courteous Service.” The Meteor and Star names survive on Amtrak’s New York–Miami route.

Variety in locomotives

Postwar modernization also came fast to SAL’s engine fleet, dominated by steam into the late 1940s. After the 1938–41 E-unit purchases, Seaboard sampled switchers from EMD, Alco, and Baldwin, and also tried exotic Baldwin road units, including 14 big “Centipedes” for freight and 3 “Babyface” DR6-4-1500s for light passenger runs. SAL’s early road diesels wore the colorful “citrus” livery of green, yellow, and orange, later supplanted by green paint schemes. Seaboard always maintained a separate red-and-black scheme for diesel switchers.

The steam roster had several classes with more than 100 Q-3 Mikados, forming the backbone of the freight fleet. Far sleeker were the M-2 Mountains, which pulled the top passenger runs from their delivery in 1924–26 until the E units took over.

In 1918, the railroad bought 15 2-8-8-2 Mallets for heavy World War I traffic, but sold them to Baltimore & Ohio in 1920. SAL’s second, more successful, foray with mallets came in 1935 with the purchase of five single-expansion 2-6-6-4s for fast freight service. With 69-inch drivers, they were among the first high-speed articulateds in the country. Seaboard bought five more in 1937 but sold all 10 to the Baltimore & Ohio in 1947. The steam stable was filled out with decapods, ten-wheelers, and pacifics. SAL streamlined three of the 4-6-2s just before the war for the west coast section of the Meteor and painted them in a modified version of the citrus scheme.

Dieselization was essentially complete by 1953. SAL ended up staying with hood units for freight service, winding up with hundreds of EMD GP and Alco RS road-switchers. In the 1960s, SAL purchased a sizeable fleet of four-axle EMD and Alco units, and also bought 20 dual-service SDP35s for secondary passenger runs but painted in the freight scheme.

W. B. Cox, Krambles-Peterson Archive

More expansion

SAL absorbed two lines in the 1950s, the first being subsidiary Macon, Dublin & Savannah in 1957. Then in 1959 Seaboard briefly became a steam owner again when it bought the 41-mile Gainesville Midland in Georgia. SAL also controlled the Tavares & Gulf in Florida.

Seaboard embraced the early 1960s trend to fast intermodal trains and was noted for its southbound TT-23, often headed by multiple E units and rated the fastest scheduled freight in the U.S. in 1963-64. Phosphate, forest products, and merchandise joined the new piggyback and auto-rack traffic as mainstays of SAL’s brisk freight business. In the 1960s, Seaboard also went after freight with aggressive advertising and thousands of new cars, including a fleet of bright green cushion-underframe boxcars.

SAL began merger talks with long-time rival ACL in 1958. The companies were doing well enough on their own, but both knew their similar route maps serving many of the same cities, often on nearly parallel lines, would not fare well under intensifying truck, pipeline, and airline competition. The Interstate Commerce Commission blessed the union in 1963, but court challenges held off the new Seaboard Coast Line until July 1, 1967.

Interesting, never rode them but when parents & I went to Punta Gorda, FL to visit my aunt, we took IC to connect up with C of G at Birmingham to Jacksonville and then took ACL to Lake Alfred, FL where we had to get off and step on another train sitting next to ours at 4 am that took us to Punta Gorda. The perks of riding on a pass, My grandpa boarded a train in St. Louis and was switched and never got off train until Punta Gorda. We did not care, it was free and we had a nice ride.

How far north did the line run?

The Seaboard connected with the RF&P (Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac) at Richmond. But all major Seaboard passenger trains began at New York City on the Pennsylvania RR which connected to the RF&P at Washington, DC.

Very nice article on the SAL. I rode the Silver Meteor from Washington, DC to Columbia, SC and back as a child, even as a young baby. My first memory of that trip was during WW 2 and all of the troops on the train. That was likely the summer of 1943 or 44 when I would have been 4 or 5. By the time I was 6, I had moved with my mother to Columbia. So I did not take this train again until my parents got back together when I was 11 in 1950. We rode the summer-time Meteor again from DC to Columbia until 1954 when I rode that trip for the first time in a car, coming down US 1 with an Uncle and Aunt (we rode back on the Meteor). Then in 1955 my father bought a car and we no longer rode the Meteor. It was always an overnight trip where I had trouble sleeping, because of my excitement about riding the train. It was on one of these Meteor trips where I first found the excitement of standing between cars with the upper part of the door open to be able to hear all what was happening and to feel the wind in your face without a dirty window between you and the outside. Now, I always like to do that whenever I can.

You will find there is a somewhat more extensive article with this title: Seaboard Air Line Railroad (SAL): “Through The Heart Of The South” — about the Seaboard RR at this web site: https://www.american-rails.com/seaboard.html

They have a nice large SAL logo and a very detailed 1940 company map from New York to Miami — but your map is easier to read.

This site also has a good article on the SAL’s train: The Orange Blossom Special. https://www.american-rails.com/orange.html

This article has a colorized photo of the new diesel engines that SAL bought in 1938 to make the OBS really Special. But I really like your photo of the steam power for the OBS taken in about 1935 with the water tank behind showing an ad for the Special on the tank. This other article also has a photo of a color post card with the 1938 diesel engines in even brighter color.

I enjoyed the story and would like to let everyone know we are restoring SAL Coach Observation Lounge the 6400. That was a part of the first 7 car Silver Meteor that ever ran to Miami. It was involved in one of the accidents during World War Two at Kittrell North Carolina in June 1942 when she was struck in the rear killing eight aboard the coach. Rebuilt it returned to service in 1943.

Can email you some photos of it today if interested

There was a Seaboard Airline. It was started in 1946 and was called Seaboard and Western. Primarily a freight/charter line.

I flew on one of their DC-4 charters to Germany in 1953.

They were a major troop carrier for the pentagon during the Viet Nam war going by the name Seaboard World Airlines.

Nice article. The SAL was ahead of my time, but I did have a nice dinner one evening in the former HQ and northern terminus in the Seaboard Coastline Building in Portsmouth VA…