When mourners gather Thursday for services at the Church of Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Auburn, Calif., it will mark a special occasion for anyone associated with the once-upon-a-time Southern Pacific Railroad: a moment to appreciate a true SP hero, James C. Mahon, known from Sacramento to San Antonio as “The Bear.”

Railroaders in charge of fixed plant rarely attract much fame, but Mahon is that significant exception, a longtime SP official who won some of SP’s most significant battles against nature. That’s especially true in the treacherous, snowbound altitudes of Donner Pass in the Sierras, where he staked the biggest part of his reputation.

Mahon died December 9 at age 87. Significantly, more than half those years were spent on the SP, where he held virtually every title that had anything to do with track, from laborer to roadmaster to division engineer.

Mahon was born to work for the SP. His father, Walter G. Mahon, was a track supervisor for the railroad’s San Joaquin Division, and Jim Mahon was born in 1937 when the family lived in Caliente, in the heart of SP’s famed Tehachapi line. Altogether, several other members of the family spanning four generations would earn Southern Pacific paychecks. Mahon would retire in 1999 with 47 years on the railroad.

It would be impossible to rank Mahon’s greatest achievements. So often, he was just the man the SP needed in an emergency, even at age 15. Yes, 15! That’s how old he was when he went to work with his father in the wake of the infamous Kern County earthquake of July 21, 1952, a massive M7.3 temblor that destroyed several miles of railroad, collapsed two tunnels, damaged five others, and closed the railroad for 25 days. Out there somewhere among the hundreds of SP railroaders brought in for the emergency, a young Jim Mahon was pitching in.

Later, in adulthood, other triumphs would come for The Bear, notably his leadership of the team in Utah that raised the Great Salt Lake causeway out of the water and reopened the Ogden-Sacramento main line in June 1986. That latter victory on SP’s Lucin Cutoff was significant. Looking at the forlorn Great Salt Lake today — its water level significantly low thanks to years of drought and water diversion — it might be hard to imagine just how dangerous the lake could be.

Forty years ago, it was a different story. High winds and water washed out about 11 miles of the causeway, and threatened up to 40 total miles of railroad. Mahon was dispatched from the Sacramento Division and his team’s effort to reopen the main line ended up as a cover story in the April 1987 issue of Trains entitled “The Bear vs. The Lake,” written and photographed by Richard Steinheimer.

One man who looks back at Mahon in admiration is Scott Inman, president of the Southern Pacific Railroad History Center and a longtime friend of Mahon’s. In assessing Mahon’s career, Inman evokes one of the greatest figures in SP history.

“I once told Jim that, to me, he was the Theodore Judah of the 20th Century,” says Inman, recalling the surveyor who first plotted the Central Pacific’s route across the Sierras in the 1860s. “Jim was humble and laughed at my comment, but if you consider that they both dreamed of trains running over Donner Pass, it begins to make sense. Judah was its visionary and Mahon was its caretaker.”

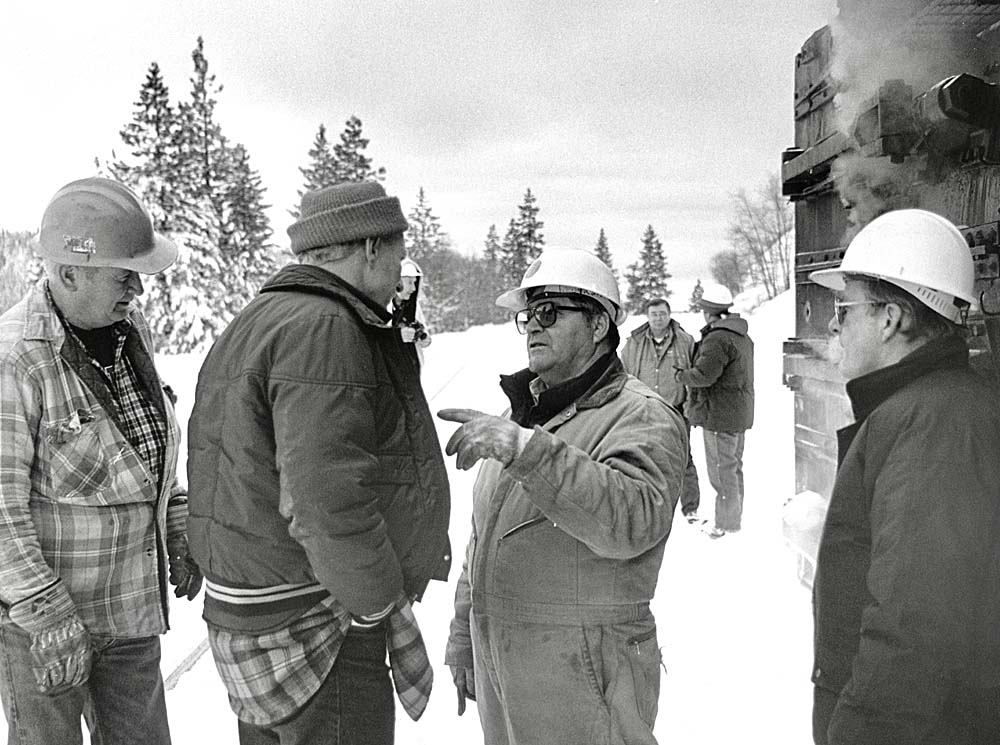

Then there’s the photographer and writer Dick Dorn, who has been one of the keenest observers of Mahon’s annual mountain campaigns. It was Dorn who wrote and photographed a definitive account of Mahon’s work in “When Snow Hits the Sierra,” the cover story in December 1994 Trains.

This was when Mahon was serving as assistant division engineer for the Sacramento Division, in charge of all snow operations. Across the article’s 10 pages, Dorn worked alongside, over, and under Mahon and his team as they revved up rotary plows, cleared snowbound switches, and knocked dangerous ice off the interiors of Donner’s famous snowsheds.

As reported by Dorn in his story, Mahon’s number one concern was for his crew. “These guys are in the field working every day, and they come up with some great ideas,” is how Dorn quoted The Bear. “It’s my job as an official to listen to them and implement suggestions that they offer. It gives them ownership in the operation and they feel proud to be a part of it. This is not a one-man show. It’s a team that works well together.”

“On one particular spreader run,” Dorn recalls, “we had been out all day and well into the night. We were plowing back up toward Norden and Mahon was on the wing with his head out the window. All of the sudden a large chunk of snow came off the wing and hit him right in the face. I was standing right next to him, he just wipes his face and looks at me and says, ‘Dorn, it doesn’t get any better than this!’ He truly loved his job and especially the snow service.”

Over the years Mahon and Dorn became good friends. The photographer remembers The Bear for his generosity. “I was introduced to Mahon in the late 1980’s by Dick Steinheimer,” recalls Dorn. “I made many spreader rides and trips on the rotaries when they made their infrequent runs. This was very special for me as I was accepted as member of the snow fighting crew. Mahon even let me bring my two sons Kevin and Justin on a spreader trip when they were 10 and 13, something they will always remember.”

Let’s give the last word to Steinheimer, who, upon watching Mahon and his intrepid crew on the Lucin Cutoff for several days concluded The Bear was “the kind of guy you’d pick to help fight a football game or a riot.”

I was the SP Meteorologist forecasting for the Overland Route from 1985 to the 1996 merger with the UP and Continued in that role until 2020. I worked closely with the “Bear” on forecasts for the Sierra Nevada for snow removal and was a close friend along with Stein and Dick Dorn. Mike Pechner

That’s quite the quote from Steinheimer!