The men in the locomotive cabs were my heroes, and I could not wait to be old enough to join them. But school and some growing up intervened. You had to be 21 years old to hire out in engine service in those days, yet my thoughts and hopes never wavered. Meanwhile, I knew that a railroad man had to have a standard railroad watch. In those days Hamilton, Elgin, and Howard were the popular watch brands with railroad men.

By cutting lawns and doing other after-school work, I managed to save up $20. My dad worked in Los Angeles and had access to many pawn shops, so I asked him if he could find a Hamilton Railway Special 992 watch for me. Luckily, he was able to get one for $20, and now I was the proud owner of a real railroad watch and had taken big step toward becoming a railroad man.

The intervening years seemed to drag by. I was 17 when I graduated from high school—still a long way from 21. In the meantime, I worked in other parts of the railroad, such as the telegraph and signal departments, where the age of 21 was not required.

Finally, my chance came. In October 1940, after a long period of no hiring, the Santa Fe Railway started hiring locomotive firemen. While I would not be 21 until October 27, I actually hired out on the 10th, hoping that the paperwork would not be processed until my birthday. Fortunately, that’s exactly what happened.

Now I had a job as a locomotive fireman and was on my way to becoming an engineer. My $20 Hamilton passed the Santa Fe watch requirements. New watches at this time cost $125. Monthly payments were available through payroll deduction and many new men took advantage of this method of securing the required standard watch.

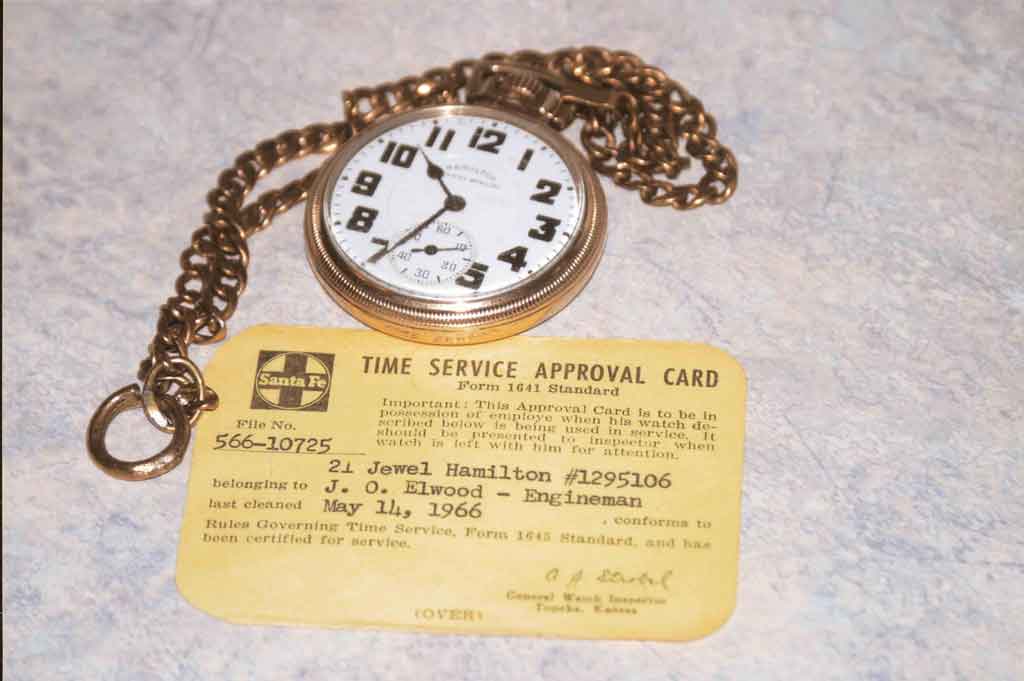

In those days (indeed, for about 25 of my 44 years service), your railroad watch had to be checked every 15 days by a standard Santa Fe watch inspector. Most larger towns that the railroad operated through had a jewelry store with a certified watch inspector. Your watch card was signed and dated every 15 days. For all these years this formal ritual was carried out without fail. Spot checks were made by supervisors at any time, and if your card was not signed you were subject to discipline.

The importance of a reliable watch in the operation of trains was a matter of deadly concern. Before Centralized Traffic Control, trains operating on single track depended on time accuracy, to the second, to facilitate the safe meeting and passing of trains.

Before starting a trip, the operating crews had to check their watches with the standard clocks located at roundhouses, dispatching offices, or where crews went on duty, indicating how many seconds slow or fast they were on the watch-register book. Conductors and engineers compared watches, as did the engineer and fireman, all to ensure that all crewmen’s watches were accurate. I carried my $20 standard watch for over 40 years, and I can still tell you its serial number: 1295106. I registered that number so many times that I will never forget it.

The watch was with me when I was the engineer on the San Diegan, train 76, in December 1965 when we hit a loaded sand truck on a road crossing in Anaheim. Our two locomotives were derailed and turned over on their sides. My fireman and I were thrown around inside the cab on impact, and a subsequent wild ride down the track ensued. The cab was filled with sand and debris. During all this my watch had become detached from my pocket and was gone.

At the Santa Fe hospital the next day, my niece visited, and since she lived in the vicinity, she went to the accident site and told the wrecking crew of my loss. They searched the cab, and found my watch buried in the sand at the bottom of the cab. The watch has a dent on the back, a reminder of the wild ride we experienced that day.

That watch, my old friend that has been with me through all kinds of experiences in my long railroad career, still ticks along to this day. It is over 92 years old.

For today’s railroaders, exact time is not so crucial for train operations. A Timex or any watch is now sufficient. Trains are met and passed by the dispatcher pushing a button, sometimes hundreds of miles away.

Nevertheless, my old Hamilton Standard Railway Special 992 is a treasured part of our family heritage. It will be passed on to my youngest son, Dan, who is also a working locomotive engineer. Dave, my oldest son, also an engineer; has his grandfather’s watch.

It may seem strange for me to write about a watch, but mine was such an integral part of my life as a railroad man, something so personal, and also a vital part of my job. Maybe this essay will provide an insight into the importance during the golden age of railroading of the standard railroad watch, my friend in time.

First published in Spring 2004 Classic Trains magazine.

Learn more about railroad history by signing up for the Classic Trains e-mail newsletter. It’s a free monthly e-mail devoted to the golden years of railroading.

A wonderful recollection especially for someone who values and owns official RR pocket watches like myself. Thank you, Jack.