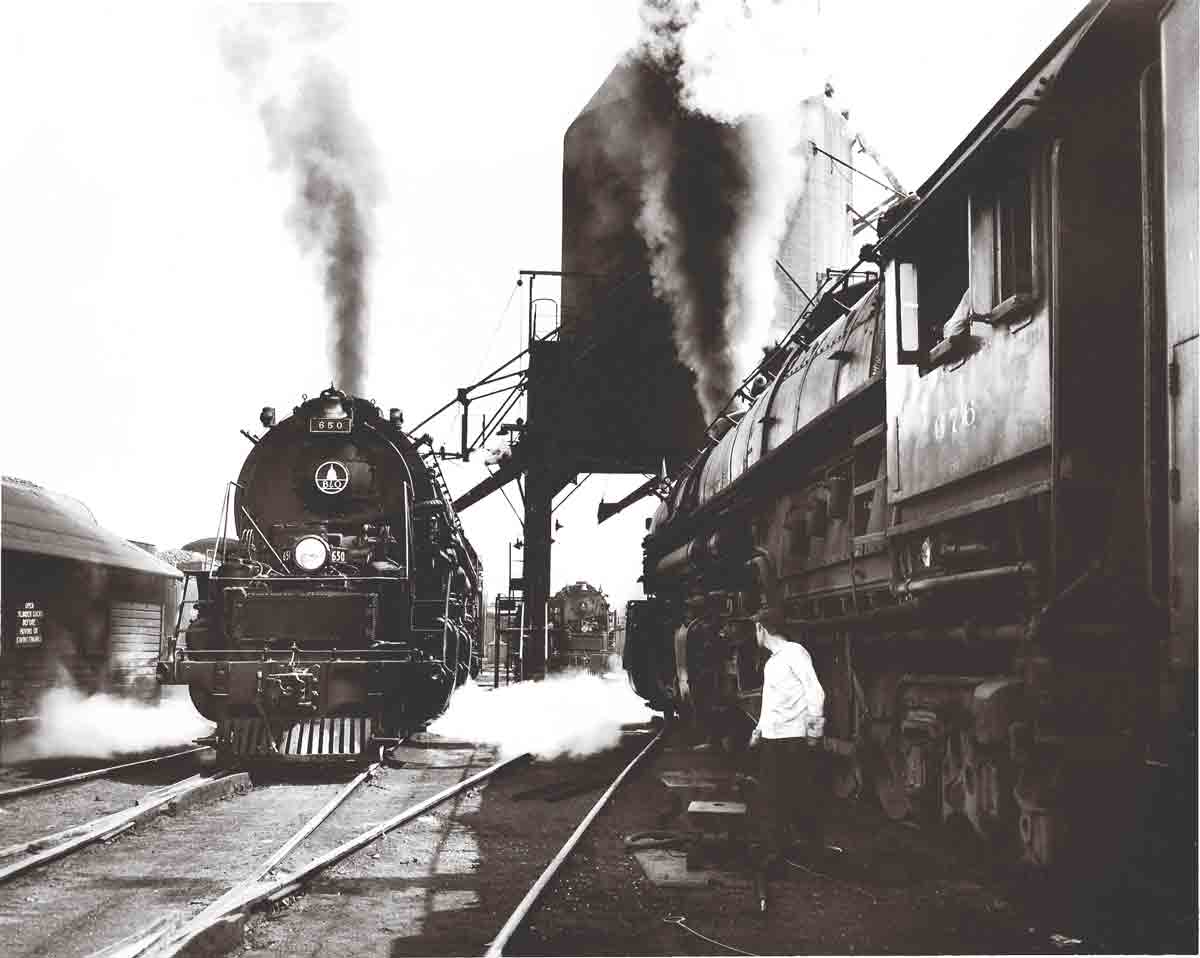

Transport of war materials had slowed, but returning veterans traveling by troop train kept crews and officials busy. And the demand for raw materials and goods now available to civilians kept railroads almost as active as during war years. Steam was still the dominant form of motive power.

During this postwar boom, in 1947 I hired out as a fireman on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at Benwood, W.Va. Benwood Junction, 6 miles south of Wheeling, occupied a strategic location. Locomotives and trains from the Newark (Ohio), Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Monongah divisions funneled into the Benwood yards.

The yards were full 24 hours a day. Many trains had to wait their turn before entering main tracks at the side of the yards. There was always activity at the ready tracks, where a great variety of locomotives, from 0-6-0s to giant Mallets, could be found.

One September day, I was called to the Road Foreman’s office. He informed me that six months had passed since I had marked up on the extra board, my record was good, and I was now qualified to be a hostler.

A hostler at a small B&O terminal had many duties. It was his job to clean fires, fill tenders with coal and water, and check supplies on the locomotives. Benwood hostlers had different jobs. The two on duty every shift were told to move engines from ready tracks to the roundhouse and, after servicing, from the house to the proper ready track.

Many firemen on the extra board disliked being called to work as a hostler. Far more money could be made firing locomotives on long freight runs, and the work was much easier.

But hostling work at Benwood had its good points. During the 8 hours of work, a hostler could be told to move an 0-6-0, 0-8-0, 4-6-0, 4-6-2, 2-8-0, 2-8-2, or one of the big articulateds. How many 17-year-olds are asked to move a 2-8-8-0 Mallet out of a roundhouse and take it for a twirl on a turntable?

The first part involved moving the giant locomotive out of a dim roundhouse. That part wasn’t too difficult. My father was a B&O engineer, and he had taught me to run a steam locomotive (a 2-8-2) when I was 14 years old. In the roundhouse, a person had to remember to open the cylinder cocks (to drain out condensed steam), put the valve gear in proper position, sound the whistle or bell, look to see that the shopmen were out of the way, release the brakes, and very carefully open the throttle a bit to get the monster moving.

Centering the locomotive on the turntable was another matter. The table at Benwood was 150 feet long, but one class of Mallets, the 7300-series EL-6a’s, was a real pain to center. These odd 2-8-8-2s, with their higher drivers and Southern valve gear, had been purchased from the Seaboard Air Line as compound Mallets after World War I.

We used the term “compound Mallets” for true Mallets, where the steam was used twice, first in the high-pressure (rear) pair of cylinders, then in the low-pressure (front) cylinders. The term “simple Mallet” was reserved for the articulateds that received high-pressure steam in all four cylinders. When referring to some Mallets that had been converted from compound to simple operation, the term “simple” also included the railroad officials who had tried to obtain a higher tractive effort without increasing the size of the engine’s firebox.

These ex-Seaboard Mallets had many faults, but only one bothered the hostler—length. When centering these locomotives, one had to remember that their total wheelbase was only 3 feet shorter than the turntable. When properly centered, the pony truck wheels were 18 inches from one end of the table and the rear tender wheels 18 inches from the other end. A real juggling act, it was.

But it wasn’t a Mallet that involved me in one of the most unusual events to happen in Benwood. One fall day, I was called to work as a hostler. The weather had been cool, but this day promised to be warm and fair. During the morning, I moved engines from the upper ready track to the roundhouse.

Later I was told to go to the house and move out a 4400-series Mikado scheduled for a fast freight at 1 p.m. In 1947 the B&O operated 604 2-8-2s, and this was a relatively modern one. It was built in 1921, had 64-inch drivers, and carried 220 pounds of steam pressure, 30 pounds more than most other Mikes. The higher steam pressure and greater tractive effort made the 4400s ideal locomotives for fast freight service. Firemen liked them because they were good steamers. Engineers said their throttles were far too sensitive.

Extensive work had been done on this engine, so several minutes were lost while shopmen gathered up tools and scurried out of the way. Finally, all was clear, and with warnings of bell and whistle I gingerly backed the big Mike out of the roundhouse and onto the turntable, basking in the noonday sun.

Before I centered the locomotive, the shop foreman called up to me that a shopman had some work to do on an injector, but it could be done on the table. At that moment the noon whistle blew, and the other shopmen downed their tools and went to lunch.

The turntable operator waited a few minutes and then said that after the shopman arrived he would turn the table, line it up for the proper track, and then have his lunch.

The shopman arrived with his tools; the operator swung the table and lined up the rails, walked out of his shack to check alignment, and went back inside.

The work on the injector took about 15 minutes. The shopman pronounced the work finished and walked back to the roundhouse. I gave two short toots on the whistle; the table operator came out of his shack clutching a sandwich and gave me a “go ahead” signal.

I opened the throttle a bit, then closed it. The 4400 slowly moved forward and then stopped, still on the turntable. I reached for the throttle again, opened it, and quickly shut it.

No movement.

Tired of waiting, I stood up to get a better grip and opened the throttle wider. Now I would get some action.

I did.

There was a scream of spinning drivers and, as I rammed the throttle closed, the table lurched sideways. There was a loud thump . . . and a sickening stench filled the air.

For a moment there was absolute silence, then pandemonium broke loose. Anglo-Saxon and Italian curses filled the air. Within minutes the turntable was filled with shopmen and officials.

Small wonder. The pony wheels of the 4400 were on rails beyond the table, the trailing truck was on turntable rails . . . but all eight drivers were firmly lodged in the heavy timbers on the turntable floor.

Locusts should receive most of the blame. They had infested the area that summer and plagued plants and people for months. The night had been cool, but late-morning temperatures had drawn them to the warm steel rails on the turntable.

Unknowingly, I had crushed many of the pests when I backed onto the table. Then, after the table was turned and work on the injector was finished, I had tried to start on slick, locust-covered rails. When I opened the throttle wider, the Mike surged ahead on multiple layers of locusts, with disastrous results.

Human nature was a factor as well. It was lunchtime and the turntable operator was hungry. What he should have done—as soon as the turntable tracks were properly lined up—was to walk over to see the end of the table and, with a long, slim rod (D-handle at one end, hook at the other), slid out a heavy, steel H-shaped device.

This device was carried between the rails at both ends of the turntable. After the table was lined up, the device was slid forward to anchor the turntable rails with those on solid ground, assuring proper alignment.

But the turntable operator was hungry, the alignment looked perfectly good, and he had wasted no time in going inside to eat lunch.

The result: When I opened the throttle wider, the drivers suddenly began spinning wildly on the slippery rails. The energy created by the outburst of power at that end of the table caused it to kick sideways . . . which brought down all eight drivers from the greasy rails.

The first person up in the cab was the shop foreman. He had enough worries without this mishap. But he wasn’t angry. He simply said: “I know . . . it wasn’t your fault. Sit down in the fireman’s seat and watch what the shopmen are doing on your side. We’ll get this S.O.B. back on the rails somehow.”

They did. With chunks of two-by-fours and re-railing frogs, they coaxed that beast back on the rails. Before it was over, the shop foreman was sweating freely from handling that tricky throttle. The engine wasn’t damaged, and much later, I delivered it to the proper ready track.

The stench from crushed locusts lasted for days. And Benwood railroadmen had a new tale to carry far and wide.

First published in Summer 2009 Classic Trains magazine.

Learn more about railroad history by signing up for the Classic Trains e-mail newsletter. It’s a free monthly e-mail devoted to the golden years of railroading.

After this ‘event’, did you earn a good railroad nickname?