I grew up just up the hill from the Electric Division in the Bronx, and I spent many hours trackside from a very early age. In the company of one or both of my parents, I watched trains most often at the stations at Spuyten Duyvil, where the freight line down Manhattan’s West Side left the passenger main to Grand Central Terminal, and at Riverdale, two miles upriver.

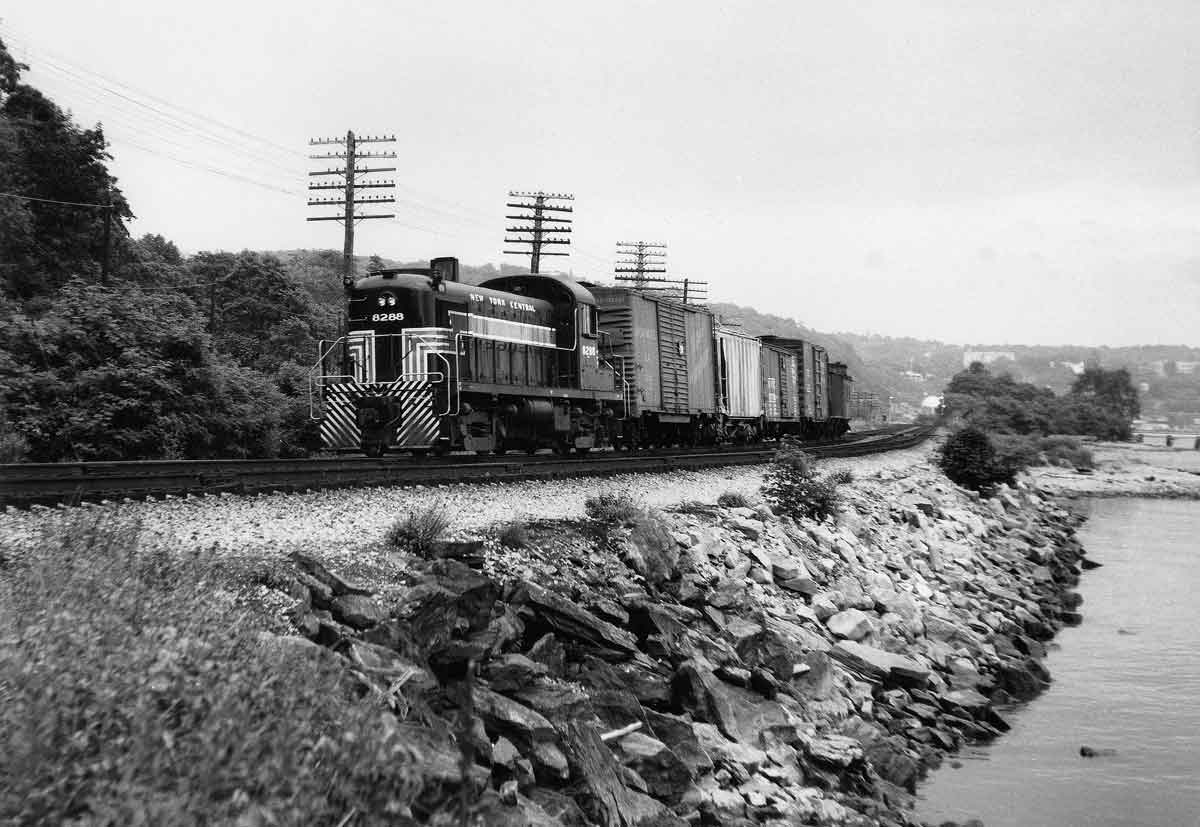

In common with most of the commuter stations on the line, Riverdale’s had a covered footbridge linking the two track-level platforms; the overpass made a good vantage point over the four main tracks, which ran straight as an arrow for more than a mile toward Spike (as all the railroaders called Spuyten Duyvil). Within sight both north and south, trussed structures spanned the tracks, supporting an array of approach-lit signals. A fifth track at Riverdale, closest to the river’s edge, saw only the local freight, pulled by an Alco RS3 — “the little diesel,” I called it as a pre-schooler.

Through freights generally used the two inner express tracks; a crossover at Spike gave Manhattan-bound trains access to the West Side line, while those headed for Oak Point Yard in the Bronx stayed on the main line until MO (Mott Haven) tower, south of Yankee Stadium.

In the late 1960s, New York City still received a lot of its produce by rail, and many an afternoon we would see a long freight with three or four GP35s on the point, heading downriver toward Oak Point, dozens of Pacific Fruit Express refrigerator cars in the consist bound for the Hunts Point markets. Red-white-and-blue “State of Maine” boxcars full of potatoes also appeared frequently. One day we found out that fruit rode in other cars, too.

I don’t know if my father had learned about the wreck before we drove down to Riverdale station, or if we went on our usual rounds and discovered it. As he carried me out onto the northbound passenger platform, we saw, instead of the serene ribbons of steel, a beehive of activity, with men and machines and twisted steel everywhere.

One of the workmen explained that the previous night’s Oak Point freight had included a Southern Pacific boxcar — one of those new hi-cube cars, taller than conventional ones — full of canned fruit. Someone had mistakenly allowed it to go east from Selkirk Yard, near Albany, and somehow it had slipped under every overpass on the way down the Hudson—until it got to Riverdale’s. Confronted with this obstacle, the hi-cube car gave up without a fight: It peeled open like the proverbial can of sardines, spilling its contents along a hundred-yard stretch of New York Central main line.

“Do you want some apricots, kid?” the workman asked. I remember hiding my face shyly in my father’s shoulder; I didn’t like apricots anyway.

For years after the wreck, a large twisted square of steel, painted red, lay on the riverbank next to our picnic spot. And for more than 30 years, until its replacement in 2003, the overpass at Riverdale bore witness to that late-night encounter: a basketball-sized dent in the girder’s bottom flange, the worst that a modern hi-cube car could do.

First published in Winter 2007 Classic Trains magazine.

Learn more about railroad history by signing up for the Classic Trains e-mail newsletter. It’s a free monthly e-mail devoted to the golden years of railroading.