Baldwin delivered the first of the steam turbines in 1947, and the C&O took the opportunity to promote the futuristic new locomotives. In 1948, two more turbines arrived and Budd began to deliver the passenger cars. The C&O sent the first of the turbines, the 500, and one of the new Chessie diners to the Chicago Railroad Fair of 1948-49.

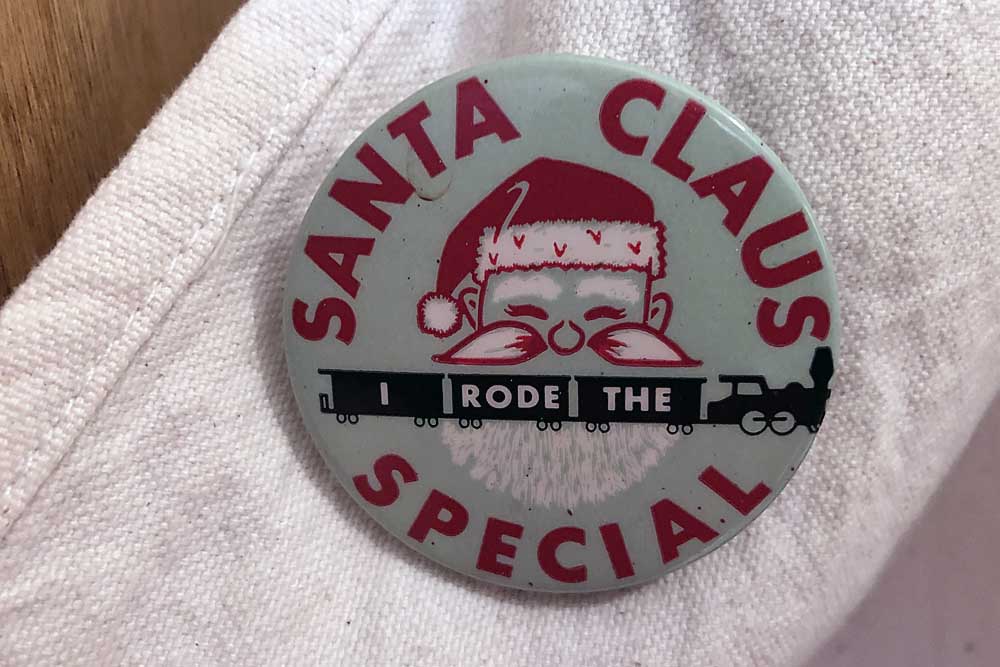

Young was so proud of the new train that the C&O started to put together two trainsets to make a system-wide tour. He felt the tour would allow thousands of potential customers to see the train and, it was hoped, decide to use it. One of the trainsets would tour on C&O’s recently acquired Pere Marquette lines in Michigan. The other would be displayed at points along the train’s intended route, including Charlottesville and Clifton Forge, Va., and Charleston and Huntington W.Va. People were impressed with the train, and young children who toured it still remember what they saw.

The Chessie never went into service, and C&O sold many of its cars to other railroads. For a time, it used the turbines on other passenger trains. One assignment was on train 47, the Norfolk (Va.) section of the Sportsman, from Clifton Forge to Hinton, W.Va., where the turbine was taken off because there wasn’t a coaling station on the westbound track. The turbine then continued west to Cincinnati on train 5, the Washington section of the Sportsman. Another assignment was between Clifton Forge and Charlottesville on Sportsman trains 4 and 47. They also handled train 2, the prestigious George Washington, from Cincinnati to Clifton Forge.

It was on one of the eastbound runs that a young Arthur Hoffman saw a turbine passing his house near Cabin Creek Junction, W.Va., during the night. The giant locomotive’s wheels were glowing with rings of fire around them as it slipped by, and the roar of the turbine was very noticeable.

As the railroad used the 500’s in service, their many problems became apparent. J. H. Workman, a machinist the C&O assigned to work on the turbine project, recalls that the constant draft in the firebox made it hard to keep the flues clean. Firemen were used to conventional steam locomotives, where the chuffing action would keep the flues open, and they had a hard time adjusting to the turbines. Screening at the rear of the locomotives would become plugged with cinders. Workman had problems finding people to work on the turbines, and remembers they had a tendency to derail in yards, even at slow speeds.

On one occasion, a publicity opportunity turned into yet another headache. A turbine and a passenger car where moved from Clifton Forge to Charlottesville for a magazine photo shoot. The train traveled the hilly Mountain Subdivision, and after the train returned to Clifton Forge the turbine was inspected. While in the shop, cracks were discovered on the wheels. This kept the locomotive out of service for two weeks.

In the end, C&O determined that there were too many problems with the turbines and the cost of operating them was greater than for modern conventional steam engines, to say nothing of diesels. The three turbines were unceremoniously scrapped.

Robert R. Young left the Chesapeake & Ohio in 1954 to head the New York Central, leaving those who toured the Chessie cars and inspected its locomotives with memories of a future that never was.

First published in Fall 2004 Classic Trains magazine.