Railroading and the 1967 Chicago snow storm: My week off, and a visit home to the Detroit area, had been planned. That its timing, at the end of January 1967, turned out to allow me to view the aftermath of Chicago’s heaviest 24-hour snowfall ever, and ride one special train and photograph another, was coincidental. I was working for the daily newspaper, the Journal-Courier, in Jacksonville, Ill., the ame small central Illinois city where I’d earned a bachelor’s degree from MacMurray College a year and a half earlier. On Monday, January 30, I drove over to Decatur, 60 miles east, to catch the train to Detroit to visit my parents and some friends. Because of the snowstorm, which had hit Chicago Thursday and Friday and then moved east into southern Michigan, and the fact that I had learned I could ride a special train out of Detroit, I canceled any thoughts of driving all the way and chose to ride the Norfolk & Western instead.

N&W had leased the Wabash (and merged the Nickel Plate and two small Ohio Class 1’s) in October 1964, but the Wabash passenger services had not changed much. Two trains each way a day linked Detroit and St. Louis, the daytime Wabash Cannon Ball and the overnight St. Louis Limited/Detroit Limited. The Chicago-St. Louis Midnight was gone, but the Banner Blue and Blue Bird still ran, although the northbound Blue Bird (a St. Louis-Chicago turnaround) and southbound “Banner” (two trainsets) were combined with the Cannon Ball between St. Louis and Decatur. The weekday Chicago-Orland Park commuter train was growing longer, and would continue to do so (today, the service is up to seven trains under Metra, and is about to be extended to Manhattan, Ill.).

West of St. Louis, three ex-Wabash passenger trains survived: N&W’s own City of Kansas City, a turnaround out of St. Louis; a nameless overnight train to Council Bluffs, Iowa (which usually ran with some freight cars); and the City of St. Louis, a through Domeliner with Union Pacific via Kansas City and Denver to Los Angeles (with a coach for Oakland, Calif.). There was also the Centralia-Columbia (Mo.) branch-line freight, which carried a coach for the occasional passenger.

In Decatur that midday, there was evidence of the storm’s fury still affecting N&W’s operations to the east. Owing to delays on the Detroit route, the Banner Blue and Cannon Ball were operating separately out of St. Louis, and that morning’s St. Louis Limited from the Motor City was running 7 hours late! I bought my ticket to Detroit, then set about to do what friends and I had often done during our college years—photograph Decatur’s daytime passenger-train action.

The Decatur varnish and the 1967 Chicago snow storm

First up was the late St. Louis Limited, train 303, which toddled in a bit after noon behind a pair of repainted ex-Nickel Plate passenger GP9’s and the consist not reversed, probably to save time or switch-clearing in Detroit. Normally most of these N&W trains’ passenger-carrying cars were “properly” at the rear, but this day No. 303’s sleeper was right behind the Geeps. Further, it wasn’t one of the usual ex-Wabash Blue-series 12 roomette-4 bedroom cars, but a Missouri Pacific car. Following were a stainless-steel coach, a heavyweight Wabash coach, the RPO, and several baggage and mail-storage cars, this time “rear-end” cars instead of “head-end.”

N&W had kept up Wabash’s locomotive service cycle, and the train dutifully changed power, to E8 3815 and a GP9. While the St. Louis Limited was in the Decatur depot, the Blue Bird flew in solo from St. Louis behind GP9 510 and E8 3808. (The “original” N&W never owned a cab-unit diesel but inherited E’s and F’s from the Wabash and wound up renumbering and repainting five E8’s, plus 31 F7’s.) Geep 510, which was properly flying cloth green flags to indicate he section following, was one of a dozen of the 22 “Pocahontas region” passenger GP9’s, all repainted from red to blue, that N&W had sent west to Wabash territory at various times after the merger.

A local freight behind an ex-Nickel Plate GP7 followed 303 out of the de-pot, passing my train, the Wabash Cannon Ball, coming into the heart of town just east of Mercer St., where a boarded-up tower guarded the junction of the lines from St. Louis and Hannibal, Mo. (via Jacksonville and Springfield). The Cannon Ball, which was running as far as Decatur as Second 304, also had two boiler-equipped GP9’s—ex-NKP 2478 and unrepainted Wabash 485—and its usual four cars: an RPO-baggage, two coaches, and a diner-lounge.

I had plenty of time to drive back to the depot, park my car, and take pictures while the Cannon Ball was serviced, before boarding for departure. This train also had exchanged power, to the ex-NKP GP9’s, 2482 and 2481, that had brought in 303. Even with the additional diesels briefly needed by the separate sections from St. Louis, and late operations nullifying the normal quick engine turnarounds at Detroit, N&W had plenty of passenger units on the old Wabash. (To illustrate how things were still “done right” in some places this late in the game, normally N&W’s inbound units into Detroit, except during the heavy holiday mail season, would just swap trains at Fort Street Union Depot and head right out again. The scheduled intervals were 30 minutes in the morning and 35 minutes in the evening!)

Wabash’s four Alco PA’s had been retired before the merger, and two of the four E7’s were gone, but the last passenger trains on the former Nickel Plate had run in 1965, so the remaining NKP passenger engines—eight GP9’s and two Alco RS36’s—had moved west and were based at Decatur, home of the former Wabash locomotive shop. Add the 10 remaining E8’s, the 13 ex-Wabash passenger Geeps, and the imported “Pocahontas” GP9’s, and the N&W was well-fixed for passenger power in the Midwest.

Our tardy 304 got out of Decatur at 1:53 p.m., 3 minutes shy of 2 hours late, and never really was able to make up any time; my last notebook entry was 10:18 p.m. at Adrian, Mich., 59 miles out of Detroit, 2:59 late. It should be noted that this year of 1967 was the “final flower” for N&W’s Wabash region varnish. Both the City of Kansas City and the Banner Blue came off in ’68. The following year, the City of St. Louis ceased to be a through train (N&W kept that name, and the service, into 1970, but UP renamed its train City of Kansas City). Also in 1970, the Blue Bird was truncated to a Chicago-Decatur service and given the name City of Decatur, and only it, the Orland Park commuter train, and the Wabash Cannon Ball lasted until the inception of Amtrak in 1971.

The 1967 Chicago snow storm and the Grand Trunk Western

After a four-day visit in the Detroit area, I headed west on Saturday, February 4 . . . on a special train. I had been, and my parents still were, active members of the Michigan Railroad Club, and MRC in those days was a traveling crowd. Many are the miles I’d put in on their excursions, mostly behind Grand Trunk Western steam but occasionally on other outings. MRC, under the guidance of the late Fred Dewey, had put together a railroad tour to the 1967 Mardi Gras in New Orleans, and had enough takers (including my parents) to ask Grand Trunk Western to run a charter train to Chicago. There, the MRC gang would change from Dearborn Station to Central Station to ride an Illinois Central special to the Crescent City. GTW at the time had two services linking Detroit (mostly people from its northern suburban stops) with Chicago, but the day train didn’t leave until 12:30 p.m., with one through coach connecting at Durand, Mich., onto train 59, the Maple Leaf from Toronto on GTW parent Canadian National. The Maple Leaf didn’t arrive in Chicago until 6:15 p.m., though, too late for IC’s plans. Hence MRC’s chartered GTW special.

The Detroit area had about 8 or 10 inches of snow on the ground when I arrived, but Durand, 67 miles to the northwest, had plenty more [page 32] and so did all the towns west of there on the GTW main line. Battle Creek, site of cereal factories, GTW’s locomotive shop, a big freight yard, and a two-story passenger station/office building, had received 28 inches, 5 more than Chicago’s official total. In fact, the first photos I took this day were not at Detroit, but at Durand, where the MRC special—three coaches and a diner-lounge—pulled alongside the platform on the Detroit Division side to exchange GP9 4915 for a pair of siblings, 4900 and 4901, and of course, crews. Grand Trunk Western in those days was more than friendly, and the sight of my mother and two other women climbing down from 4915’s cab after their ride up front from Pontiac just proved it. In fact, yours truly and I forget how many others took their place in the two Geeps’ cabs for the fast 76-mile ride to Battle Creek, a crew-change, water, and fuel stop. Since my footwear from “balmy” central Illinois was not suited for tramping around in deep snow, my photo angles were restricted at both Durand and Battle Creek. (A historical note: These two Geeps were the Trunk’s first passenger diesels, acquired as Nos. 1750-1751 in 1954.)

Chicago a week after

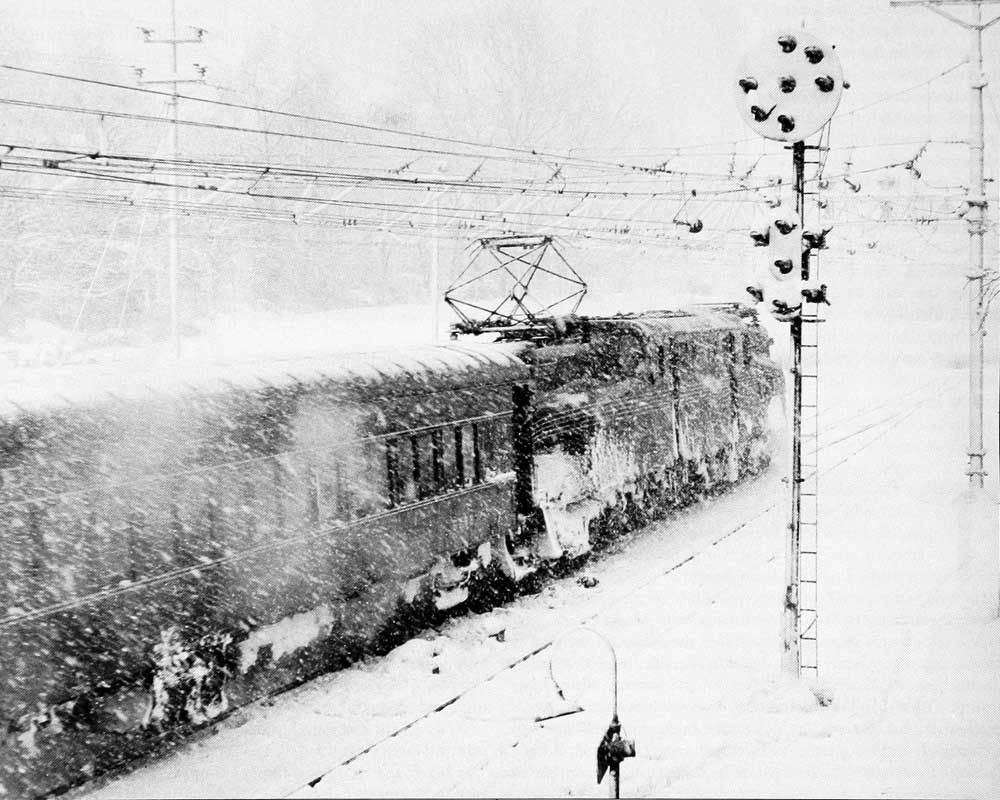

Back in the coaches, the run onward to Chicago was as routine as possible, under the conditions, and my next photos were on the Windy City’s South Side, from a vestibule Dutch door looking down from GTW’s elevated right of way south of Elsdon Yard onto the side streets that still showed the effects of the storm [pages 32-33, at 65th Street and Central Park Avenue]. Chicago would not see the likes of this again until 1979, the January 12-14 blast that put down 20 inches of new snow atop a cover of 7 to 10 inches left over from a New Year’s Eve storm, which resulted in Chicago’s deepest-ever snow cover. That storm strangled the city, and is credited with the ousting from office of Mayor Michael Bilandic.

The 1967 blizzard was no slouch, either. Snow fell for more than 24 hours beginning about 5 a.m. on January 26, and drifts of up to 6 feet were measured. Cold weather and off-and-on snowfalls over the next 10 days created more chaos, and although most trains continued to run—as GTW and IC proved—most buses, cars, and planes did not. Loop hotels were full of commuters who couldn’t get home; O’Hare Airport was jammed with stranded travelers; businesses closed for several days. Simply finding a place to put all the snow became a problem, so a lot of it was loaded into freight cars and shipped south to melt. Police arrested 273 looters, and 60 people died, most of them from heart attacks while shoveling snow.

Such tragedy, however, did not stop the Michiganders bound for Mardi Gras on that following Monday. For the special move south, Illinois Central had rounded up a consist of 10 cars (an IC combine for crew, a diner, and Pullmans in IC, Santa Fe, SP, and UP colors), which left town behind E9A’s 4038 and 4040 a bit before 5 p.m. as “Second 5,” a following section of the Panama Limited, which IC called, on a sign at the Central Station track gate, “America’s Finest Streamliner.” Of course the regular train, “first 5,” left on-time, at 4:30.

In between the Panama Limited sections, at 4:45, IC dispatched train 9, the Seminole, for Birmingham and Jacksonville, Fla., behind Central of Georgia’s two E8’s, 812 and 811, which were painted in IC’s passenger colors. I and Norm Herbert, a Michigan friend who rode the GTW special to a dentists’ convention in Chicago, took an IC electric from 12th Street (a platform outside Central Station) out to the 27th Street suburban station to photograph the streamliners from the platform. “Second 5,” the special, just barely beat dusk.

I went on to visit friends in the suburbs and returned to Decatur the next day to retrieve my 1961 Ford Galaxie and go back to work. I hadn’t been in the “Great Midwest Blizzard of 1967,” but I sure saw the results of it a week later, from the comfort of a couple of passenger trains.