In the late 1960s and in to the ’70s, I had numerous rides on Toledo, Peoria & Western freight trains in both directions out of Peoria, Ill., where I grew up. The TP&W interchanged with the Pennsylvania Railroad and its successors 108 miles east at Effner, Ind., and with the Santa Fe 114 miles west in Fort Madison, Iowa. (TP&W rails didn’t reach Fort Madison, but joined the Santa Fe at Lomax, Ill., from where TP&W trains ran about 16 miles west to the interchange point.)

My friends and I discovered that through a quirk in the TP&W’s permission to abandon passenger service in the 1940s, the Interstate Commerce Commission had requested that they carry people who still wanted to ride. Passengers would be accommodated in the caboose. I recall that the tickets were very inexpensive and often the crews didn’t even want to fuss with actually selling you a ticket, but gave you permission to ride regardless, after signing the appropriate release.

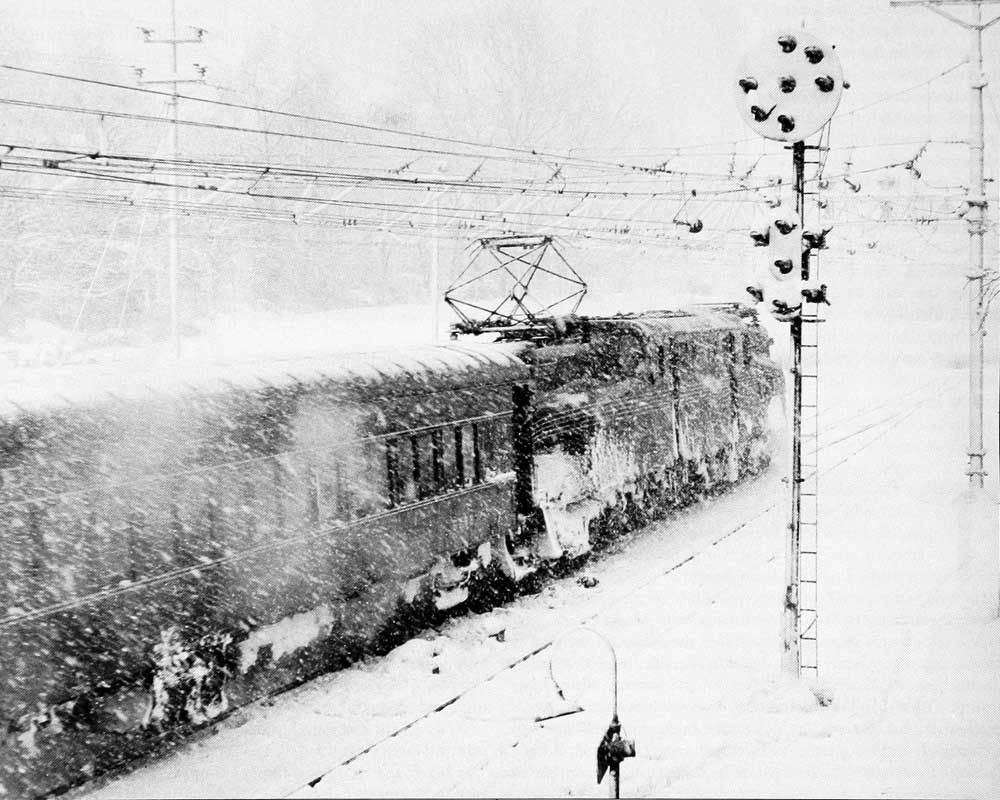

Bon French photo

Of course, we really wanted to ride in the engine and not the caboose, and most of the time the crews obliged. But one time in the summer of 1970 we had a crew that wanted to stick with the rules, so we had to ride in the caboose. This was on train 121 to Fort Madison, which was fun because we got to ride the high iron of the Santa Fe at 60 mph for the final miles to Fort Madison.

We stayed overnight and returned with the same crew the next day (also in the caboose). I learned two very important lessons about railroading that day.

One was that 8 hours of rest did not mean 8 hours of sleep. The required 8-hour rest period between runs started the minute we stepped off the train in Fort Madison and ended when we got back on the train very early the next morning. This meant that getting to the hotel, eating dinner, getting to bed, eating breakfast, and getting back to the yard were all part of “rest.” The crew had the crew caller wake us along with them about 4 a.m., so in practice we got only about 4 hours of sleep.

By the time we rolled east out of town on No. 122, the sun was up dawning on a beautiful, and soon to be warm, summer day. A few hours into our ride home (I remember being in the cupola at this point), I found it impossible to stay awake. Riding in the locomotive was somewhat different in that there was a lot of engine noise, crews calling signals, whistle blowing, and so on. Staying awake up there was easier. Back in the caboose, it was relatively quiet, and the rocking of the train and the lack of sleep made it simply impossible for me to be alert. I realized then that crews worked in this sleep-deprived state on a regular basis, creating potentially dangerous situations. I talked with them about it, and they just said they learned to live with it. But trying to stay awake is not something one can easily force yourself to do. That was Lesson No. 1.

Lesson No. 2: To get some fresh air and stay awake, I decided to stand out on the back platform of the caboose. The crew admonished me to be careful, which I took seriously. And a good thing too, since before long, I heard a big clattering sound coming at me, which I knew to be slack running out. I was already holding onto the handrails, which probably saved my life. The caboose lunged forward with a massive jerk, throwing me into the ladder that led to the roof. The slack action came so fast that there was no time to react once you heard it, and there was no way I could have stayed on my feet without holding on to something. I could have easily been thrown off the rear of the train. I never knew it could be that violent.

Even in my sleep-deprived state, I never moved around the caboose for the rest of the trip without holding on to something. I had had a big scare. The west end of the TP&W travels through up-and-down country unlike the east end, which is essentially flat once you climb out of the Illinois River valley. There were a few more slack run-ins and run-outs on our trip home, but I was prepared for them.

After that ride, whenever I was trackside watching a caboose go by, I had a newfound respect for the very real dangers therein.

Bon French photo

Check out Kalmbach Books’ Guide to North American Cabooses, by Carl Byron with Don Heimburger

A small ‘nit’ in a most enjoyable article: The required rest begins when the crew ties up, and ends when they go on duty. Still, as mentioned, those 8 hours then included food, sleep, bathe [if possible], and a 90-minute call before the on duty time. Net available sleep: 5 hours, if you’re lucky.