I became a railfan at age three, near the end of World War II. Awaiting the return of my naval officer father, I sat in our West Philadelphia kitchen window facing one of the busiest divisions of the Pennsylvania Railroad — the four-track electrified main line to Harrisburg. The parade of wartime tonnage, plus express and local passenger trains and MP54 commuter car, was endless. Leading most trains were PRR’s GG1 and P5a electrics.

As the years passed, my folks moved three miles from the tracks. But my grandparents moved into a formal apartment house in Merion Station, about a mile and a half west of my first perch, again facing the Standard Railroad a hundred yards away.

I would spend hours in their sun porch window, enjoying a nearly unobstructed view of that Main Line boulevard. About a half-mile east of the Merion depot stood a signal bridge guarding the approaches to the railroad’s then-huge West Philadelphia classification yard. Signals for two eastbound tracks and eastbound traffic on the third bidirectional track were plainly visible from the station platform.

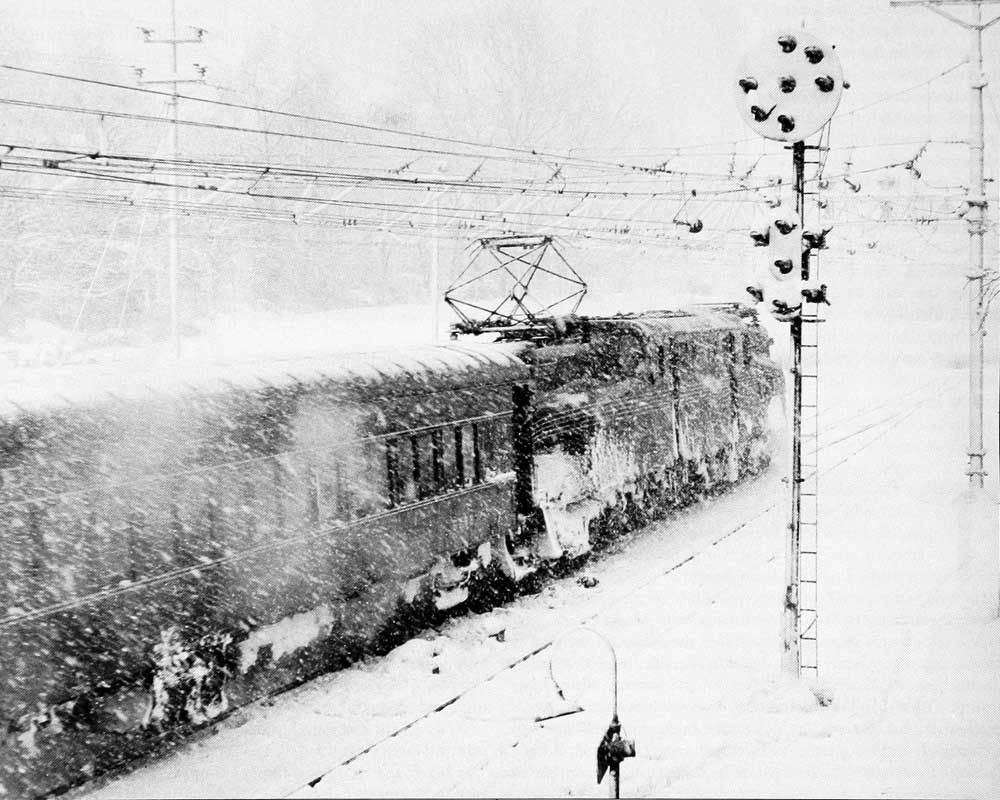

On those few days each winter when snow would close my school, somehow I would manage to make it to grandmother’s house to watch the show on the Pennsy. On one particular February 1958 day, as I peered out the window through an extremely dry snowfall of almost crystalline flakes, it struck me that, for a weekday, the Philadelphia-Harrisburg main line seemed eerily quiet. An hour after an empty string of coal hoppers had kerclack-kerclacked to the west behind diesel road power and its helpers had returned, a GG1 quietly brought its eastbound passenger train to a halt on the second track, with the motor peeking past the right of the station building! I sensed something major was afoot.

While the oil-fired steam boiler in the GG1 continued to supply heat to the train, the engineer dropped the pantograph, breaking contact with the catenary. After a half hour or so of no visible activity at trainside, I donned a jacket to run across the parking lot for a closer look. At age 15, I was not about to question the engineer, fireman, or conductor, who by this time were standing on the ballast, shrugging their shoulders and scratching their heads as to why they had stopped here with “approach-medium” displayed on the home signal. I did overhear a word, either “sparking” or “arcing.”

As the conductor crunched into the stationmaster’s office to use the company phone, the engineer and fireman fished a long pole from under the G’s body shell and nudged both pantographs from their locked-down positions, up to contact the 11,000-volt wire.

By the time the conductor finished his conversation and had stepped back outside onto the platform, about 45 minutes had elapsed since the train had stopped. The only part of the conversation I could overhear was the engineer saying, “I dunno. We got power, the lights are on, the blowers are working; it just won’t go.” As I recall, the conductor responded, “Yeah, wait’ll you hear this. It’s like every G on the road has just quit! The 54s are workin,’ the P5s are working, but not the Gs!”

At that moment the home signal, which had been changed to “stop” after the conductor made his phone call, blinked to “slow approach.” “They said they’d give us the signal in case this thing gave up bein’ a mule!” the conductor hollered up. “Want me to try it?” the engineer asked. “Highball!” the conductor responded, shrugging his shoulders, laughing heartily to himself, shaking his head and turning to go back to the warmth of the station building, fully expecting the train would not budge.

The engineer leaned down on the 22-notch controller and advanced the handle one click. Then came the call down from the cab, “Hey! She wants to move!” The conductor checked the first track nearest the platform, then stepped carefully over the rails to climb into the first vestibule aboard his train, as the engineer released the brakes and eased downhill.

Amazingly, immediately behind that train-maybe 50 yards back-was another passenger train, but with diesels on the point. Apparently, the GG1 scheduled to pull that train had not answered the call at the power change in Harrisburg, so the diesels were left on. I stood on the platform as that train, too, crept to the “stop” at the home signal, then proceeded as the signal blinked to “approach.”

That evening, newsman John Facenda on Philadelphia’s WCAU-TV explained that the very fine snow had entered the big electrics’ air intakes, passed through the filters, and had shorted out their motors, immobilizing most of the fleet, paralyzing freight and passenger service well beyond Pennsy’s New York-Washington and Philadelphia-Harrisburg electrified territory.

According to authorities, after the locomotives had stopped, the snow and ice had melted and the water had evaporated. Slowly the GG1s had returned themselves to service, almost as mysteriously as they had withdrawn, though some had to be hauled to shops for repair. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had had a front row seat to railroad history in the making. That snow, whose flakes were especially fine at the level of the GG1’s relatively low air intakes, was the reason for the eventual appearance of the ugly, oversize air intakes just beneath the pantographs on many GG1s. Years later, when the Amtrak paint job was applied to some, it gave the sensually beautiful GG1 the appearance of Dumbo in clown greasepaint.

The GG1 has always been my favorite locomotive. Whether leading a passenger express, hauling freight, helping lesser engines move trains, or sitting in a museum, the GG1s haughty, almost snobbish face and powerful, graceful curves have captivated me.

Still, I’ll never forget the day the GG1 fleet called in sick.

Thank you for a great story