But railroads can hold an individual together. I am sure of that. As the saying goes, I’ve been there. And even 40-some years afterward, I can still remember how it felt.

If it’s 1970, and you’re 24 years old and a graduate of the Naval Academy, volunteering for Vietnam is a no-sweat thing to do. They tell you that you’ve been trained for combat, and you believe them.

Things look different four months later when you’re sitting in San Diego waiting to switch sides of the Pacific. You wonder why you traded a haze-gray destroyer in the East Coast “peacetime navy” for a green-and-black camouflaged in-country gunboat.

You read the after-action report of a sister ship that was beached up the Bo De River with half her crew wounded after taking a B-40 rocket in the hydraulic tank and three more in the pilot house. That is not the kind of situation one learns how to handle in leadership case studies back at Annapolis.

So you put yourself on automatic and do what comes naturally. Focus your mind and tighten yourself up. Cut ties with everyone; west of the Philippines you’ll be on your own, so get used to the feeling. Forget about your parents back in West Virginia. Ignore the bride who was foolish enough to accept the proposal you made before your mind got locked onto Southeast Asia. Go out of your way to avoid new friendships. And definitely, most definitely, count the days you have left.

But everyone needs to hold onto something. So you hold onto a piece of railroad.

The logic is flawless. A railroad just passes you by and expects nothing. It doesn’t care if you’re too scared to talk. It won’t miss you when you leave, and it won’t care if you don’t come back.

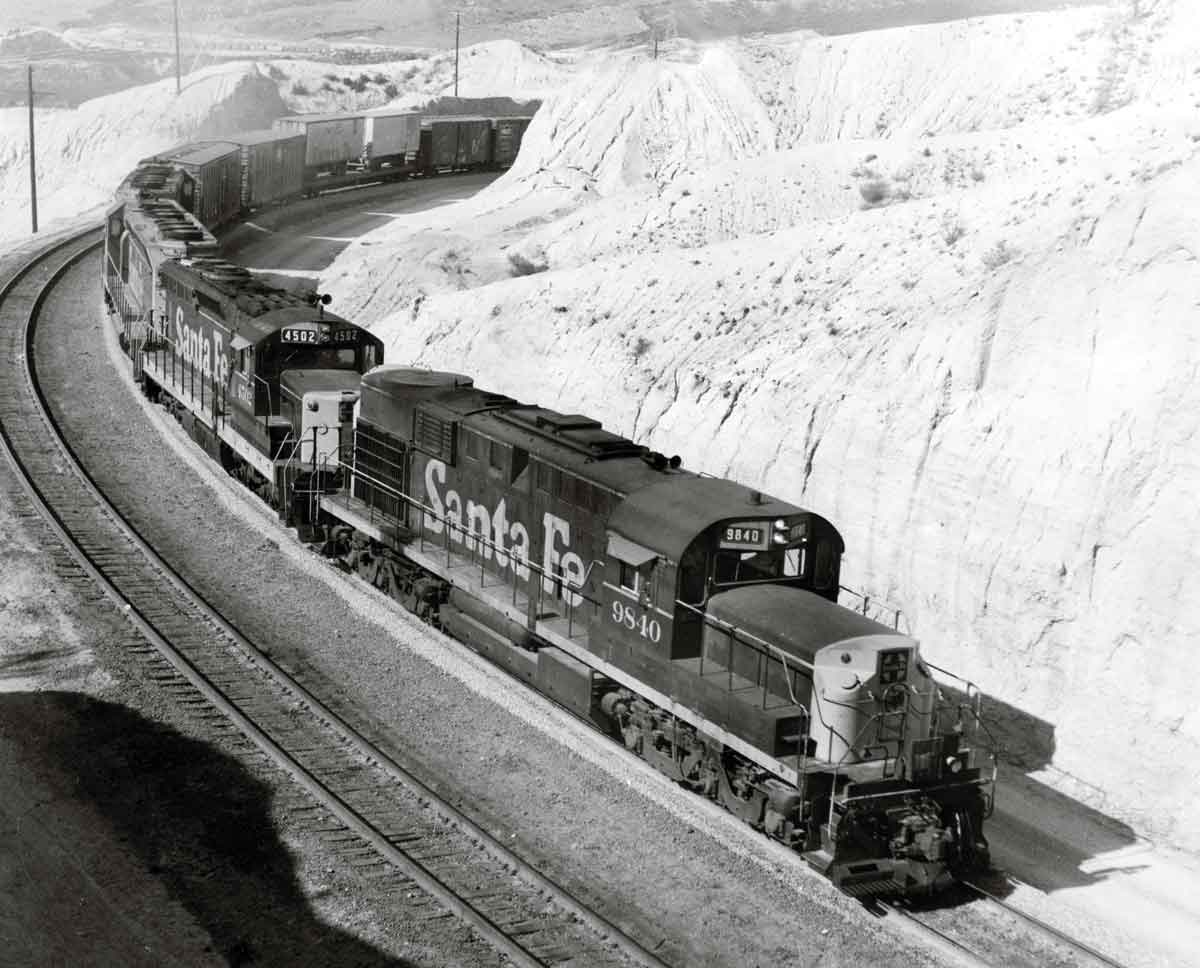

The railroad I held onto was the double-track Santa Fe line that passed through Cajon Pass at Summit, Calif., and linked the southern part of the state with the railroad’s transcontinental main line at Barstow (137 miles northeast of Los Angeles). Union Pacific held operating rights over the route from Riverside Junction (59 miles east of Los Angeles and 46 miles west of Summit) to Daggett (9 miles east of Barstow). A lot of trains moved through Summit.

Monday through Friday in San Diego, I got ready for my war. I learned technical details: “The model LM-1500 jet turbine consumes approximately 1,000 gallons of fuel per hour at flank speed, however the ship’s ability to attain flank speed is primarily dependent on the temperatures of bearings in the drive train.” But I paid even closer attention to what wasn’t in the books: “You get an ambush up the river, it’s best to sit and shoot it out. Run from it, and you’ll likely get greased around the next bend because they’ll be even more of them waiting for you, probably on both banks.”

So during the week I counted the days. But on Saturday and Sunday I counted the trains passing through Summit. The traffic was quite different from the mineral and secondary freight operations I had grown accustomed to back East. It was interesting enough to keep me occupied.

UP’s City of Los Angeles streamliner passed in each direction behind four- and five-unit sets of E8’s and E9’s. There was a steady stream of Santa Fe and UP manifests, and these were often headed by characteristically “western” power. UP was taking delivery of its twin-engined DDA40X Centennials, and these appeared occasionally. F45s were regulars on Santa Fe’s hot Super C piggyback train. Members of its 50-unit fleet of Alco RSD15s also passed through, as did their EMD SD24 contemporaries.

So for 12 hours or so each weekend, I stood above the tracks on the curve just west of Summit and thought about La Grange and Schenectady, San Bernardino and Barstow. Then, late Sunday afternoon, I would drive back to the Navy. My car would take me as far as San Diego. But since I was away from the trains, my mind would continue on west to Nam Can, Phu Quoc, Tiger Island, and other obscure places that suddenly became vitally important when they showed up on my itinerary. Yet that was all right — thanks to the Santa Fe and Union Pacific, I’d been away from all that for a spell and had become capable of handling it for a while longer.

I went to Vietnam, and I came back. But I’ve never returned to Summit, and I hope I never do. You see, I’m holding Summit as sort of an ace in the hole. It’s the place I’ll go if I ever again have to do something important that I’m not sure I can do. If that happens, I’ll simply head for Cajon Pass, watch some trains, think back a few decades, and then go do whatever needs to be done.

So, the next time you visit a railroad line that’s special to you, give it some serious thought. Maybe it is only a diversion from the office or a pleasant place to spend a sunny afternoon with some friends. But someday it could become much more than that. Someday that piece of railroad just might be what holds you together. As I said, I’ve been there.

First published in Spring 2008 Classic Trains magazine.

Learn more about railroad history by signing up for the Classic Trains e-mail newsletter. It’s a free monthly e-mail devoted to the golden years of railroading.