1950s EMD customer relations: At the height of dieselization circa 1950, the volume of orders pouring into Electro-Motive Division was sufficient to require three production locations: La Grange, by far the largest; Plant 2, a former Pullman Co. facility in South Chicago; and Plant 3, the ex-Cleveland Engine Corp. facility in Cleveland, Ohio.

However, by 1953, sales had decreased to the point the Cleveland plant was winding down production and would close in 1954. Switcher and GP7 construction previously allocated to Plant 3 was being absorbed at La Grange.

Particularly during this transition period, there were bound to be occasional “misunderstandings” between supplier and customer.

Boston & Maine’s dieselization

Like many railroads in 1953, the Boston & Maine Railroad was dieselizing as fast as finances would permit. That year the board of directors authorized the purchase of six GP7s from EMD. A Letter of Intent allowed the GP7s to be assigned a production slot in La Grange’s schedule while the Equipment Trust funding was negotiated between the B&M and Boston-area banks.

It was admittedly a small order, but between the years 1950 and 1952 the B&M had purchased 17 GP7s, 14 SW1s, seven SW7s, eight SW8s, and 12 SW9s, as well as 35 units from Alco.

Several months later, as the units neared completion on the erecting floor, B&M Mechanical

Department Superintendent Ernie Bloss sent Assistant Engineer of Tests Kenneth F. McCall to EMD to inspect and formally accept the locomotives for delivery. This pre-acceptance inspection was, and continues to be, standard practice dating back to the earliest years of contract locomotive production.

EMD’s first shot at customer service

Upon inspection of the first one or two units, McCall made it clear to his EMD production counterpart that certain specified items were not present on the locomotives and needed to be installed before acceptance was possible. The EMD supervisor’s response was, “Just take ’em the way they are or we’ll sell to the next customer.”

That was not a wise statement to make to Ken McCall, whose values and black-or-white view of the world were known, respected, and sometimes feared by his B&M staff associates. A shall we say “boisterous” vocal exchange occurred, apparently on the production floor beside the locomotives, which culminated in McCall stating, “You do that [meaning sell the GP7s elsewhere]. I’m not taking them as is!” Then he walked out.

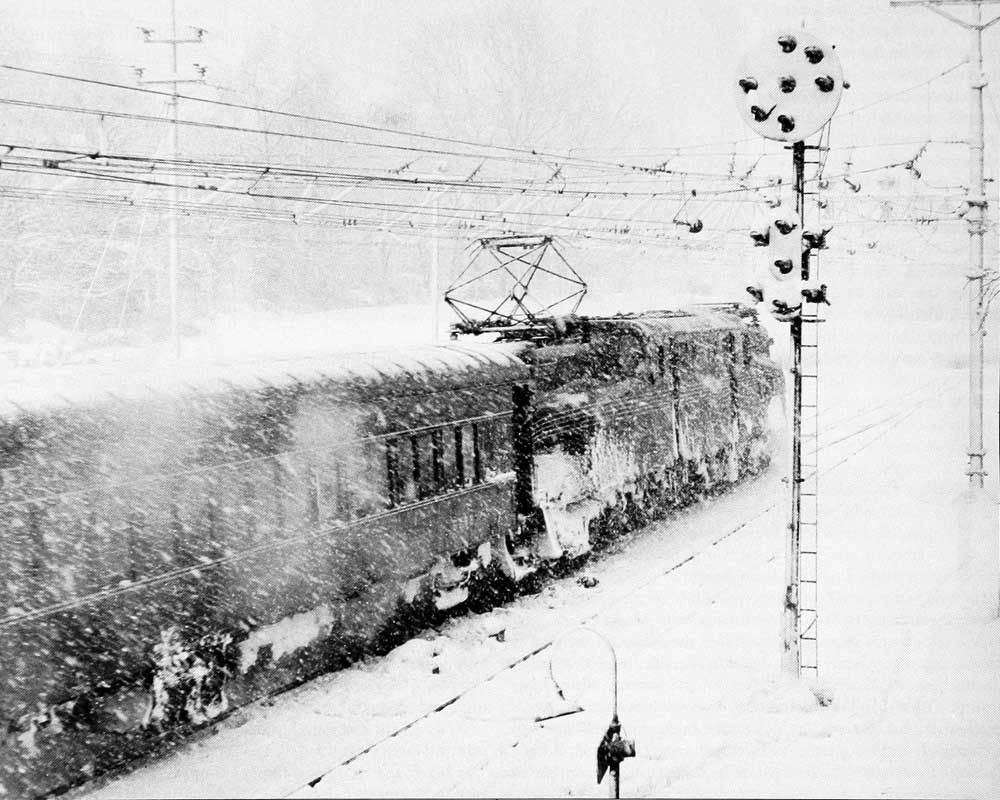

McCall departed EMD, contacted B&M headquarters and left Chicago late that day on New York Central’s Boston-bound New England States.

EMD makes things right

Approaching Buffalo near midnight, McCall was “gently awakened by the Pullmanconductor requesting I get dressed promptly, detrain at Buffalo, and board the next westbound train for Chicago.” The conductor continued: “Your westbound accommodations have already been booked, and, I am to inform you that EMD has committed to meet its contract obligations.”

One might suspect that the Bell System, the sole provider of long distance U.S. telephone service at that time, had a very profitable afternoon on its trunk line between La Grange and the B&M’s offices at 150 Causeway Street in Boston. And long-distance phone service in the 1950s was very expensive. Likewise, it’s safe to presume that Ken McCall slept much better westbound than eastbound that evening.

The record implies there was payback. B&M’s next order for road switchers went to Alco for 13 RS3s in 1954, followed by two more RS3s in 1955. In fact, EMD did not receive a road locomotive order from B&M until new railroad management was installed in January 1956. Even then it was for the conversion of 48 tired FT locomotives into 50 new GP9s “containing some rebuilt and/or remanufactured parts,” to be delivered between October 1956 through 1957. EMD accepted the order with about a 30% credit off list price.

That such as the above occurrence would be documented in personal correspondence is rare. Generally, these sagas are swept under the corporate rug and quickly forgotten. However, the above excerpted comments are contained in several circa-1960 personal letters between McCall and noted postwar steam locomotive designer Dr. Adolph Giesl Gieslengen, of Vienna, Austria. The two apparently were longtime pen pals if not personal friends. The correspondence was discovered by your author in the Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society archives.

Another side to the story

What makes this event even more unusual is that the late Max Ephraim, EMD’s chief engineer in the 1960s and ’70s, also recalled that day. In 1953, Ephraim was the GP7 project engineer, having begun design under EMD’s legendary Chief Engineer Richard Dilworth. Ephraim subsequently continued in that capacity to oversee production when Eugene Kettering replaced Dilworth upon the latter’s retirement. Ephraim later wrote this to the author: “Some of our [EMD] people were afraid when he [McCall] showed up, but I had admiration for a man who did his job well. As a matter of fact, I said at the time we should hire him to help us make a better product!” It must have been quite a show! There also is anecdotal evidence that the above was not a unique occurrence. Something might have occurred between the Santa Fe and EMD in early-to-mid- 1948. Suffice it to say the EMD sales manager responsible for the Santa Fe account was not likely pleased when ATSF ordered 12 Alco PA/PB units rather than 16 EMD F3s for late 1948 delivery.

No matter how big an organization is, it ignores “The Customer is Always Right” axiom at its peril.

This is a fascinating account of of what, in terms of the overall corporate environment, would have been a relatively small incident. Yet it’s a fairly detailed story, and it wouldn’t have been possible without access to the personal records of Kenneth McCall. Having been an executor myself, I can certainly appreciate the linkages that made it possible to share this story with the rest of us here! Stories like this are what make Classic Trains my favorite publication by far. Thanks for sharing this.

I recall seeing photos of those FT’s passing through East Altoona en route to CB&Q and La Grange. There was little, scrappy B&M sending retired road diesels for a second generation and in the yard were PRR I1sa 2-10-0’s working in road service. Who knows, an M1b 4-8-2 may have pulled the FT’s from Enola to East Altoona.

This is an excellent insight into the issues encountered when dealing with a large corporate entity such as EMC/EMD. My involvement with B&M historical research also had me become acquainted with the late Kenneth McCall’s no-nonsense demeaner toward railroading and other aspects of his life. Indeed, before his passing he was involved in the early developing years of the Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society, that is until some sort of rift separated him from same. Fortunately, after his passing, his heirs were more understanding of preservation efforts and saw fit to pass along all of Ken’s remaining materials for posterity. I was directly involved in that delicate transfer and am eternally grateful of same.

Regarding the story of the B&M GP-7’s, it would be interesting to find out what exactly were the issues encountered that caused his angst. The early GP-7s were an interesting lot, whereby all in the above were equipped with steam boilers intended for passenger service. However, a major intention was that all would be equipped for suburban passenger service that required boilers and head end lighting generators, the latter being for the very short runs requiring same. None in the first group had train lighting generators for said service (perhaps because it was not an available option then?), and only the first two (1561-1562) in the second group had this feature. However, inexplicably to me at least, 1563-1561 in the second group were lacking M.U. capability, as well as being equipped with #6BL brakes rather than the #24RL of the previous. One might easily speculate why McCall might be displeased as I suspect that all of those GP-7 units in the 1952 order should have been identical in their appointments for their intended service. Indeed, perhaps the compromise for accepting the order may have been a price reduction and also equipment for retrofitting the 1563-1571 with M.U. capability, which indeed they were as soon as possible. Also, three units in the original first order would obtain train lighting generators as well. This I feel was so that they could cover the down time when the second order was getting the M.U. treatment. It was certainly an interesting period in B&M dieselization.

Great story, Carl.