Anyone who spent much time at all as an “excepted” (non-union) employee could expect, sooner or later, to be required to work railroad strike duty. This was especially true if he was a supervisor in the mechanical, engineering, or operating departments. Your personal feelings were inconsequential when these events occurred–you did what you had to do, unpleasant or dangerous as it might have been. In some 40 years of railroading, though, I never knew a supervisor to resign because he was required to perform strike duty, even those promoted to their positions from the ranks of union employees.

Strike duty usually came about because of: the necessity to switch industries (customers) continuing to operate while their employees were on strike; the necessity to operate trains across picket lines into facilities of connecting railroads whose employees were on strike; and when the negotiators couldn’t quit pounding their fists on the tables and shouting at each other, and all the convoluted “remedies” of the Railway Labor Act didn’t work, it became necessary to operate trains on your own railroad while your own employees were on strike.

Picket line duty seemed to bring out the worst in some strikers. The aim of picketing is, of course, to try to shut the railroad down. Seldom was it effective with a company determined to keep running, and this naturally enraged many strikers; many things have been done on picket lines and elsewhere over the years that wouldn’t have been done by reasonable people not acting under mob conditions.

The longer the strike, of course, the worse the animosity becomes. This is for two reasons — the strikers are not doing an effective job of keeping the company from operating, which is frustrating; and the equal frustration of knowing that the longer they’re out on strike, the harder it’ll be for whatever gains they get from the strike to compensate for what they lost by not working. Some of these animosities lasted for generations. I went to work in the rail industry in the mid-1950s, and when I started, there were still folks around who were bitter about the Shopmen’s Strike of 1922.

I knew of one industry whose picketing employees would lay a U.S. flag across the rails of the lead into their plant. If you ran over the flag, you were accused of desecrating it. This seemed an odd logic, indeed. A reasonable person might expect that such desecration would begin with laying the flag across the track and placing it in position to be run over, but most folks’ definition of “reasonable” in that situation would be at odds with that of the strikers.

And, of course, there was the picket line “repartee.” An assistant road foreman of engines (who held seniority as an engineer) whom I knew was operating a steam engine across a picket line into a foreign line yard. A picket shouted, “Hey, buddy, are you a promoted locomotive engineer!” The assistant road foreman of engines shouted back, “Hell no, I’m a furloughed telegraph operator!”

Another time, a picket shouted emphatically to the stand-in engineer, “You’re taking my work!” The reply was “Fine! You get up here and do your work and I’ll get off and go home!”

Strikes of industries you served might last a while they were a pain because they interrupted your normal routine, and nobody enjoyed the abuse of running a train across a picket line of angry folks who weren’t striking your company, anyhow. It was all in the “demands of the service,” though.

Strikes against railroads themselves tended to be short because most U.S. Presidents would quickly sign a “backto-work” order requiring the unions and the companies to get “back to” the bargaining table and “work” things out. There were, however, exceptions.

As luck would have it, I was working in management for the Rock Island’s Chicago commuter operation when the clerks’ union went on strike in 1980. Since I had run trains elsewhere, I had been given the Rock’s engineer’s examinations shortly after I was hired, which placed me on the short list for strike-duty cannon fodder.

So, on day 1 of a 38-day strike — the President evidently didn’t figure the Rock was worth a few strokes of his pen — I found myself running a switcher in the yard at Blue Island.

This duty was unexciting and uneventful, except for having the opportunity to run some of the Rock’s Alco Century 415s — strange little creatures they were, indeed-and becoming acquainted with the quick-releasing ABD-style car air-brake valves that had come into vogue since I’d done most of my freight-train handling.

After about three weeks, they sent me out on the road, where I ran between Blue Island and Silvis and Peoria. The pickets, fortunately, were pretty benign; aside from a few airhose slashings, there were few acts of real malevolence in our area.

This was almost 20 years ago, though, and we tested some of the theories about manning trains that are not-so-rarely practiced today. We never had more than two men on a train. The Blue Island-Bureau turnaround local freight, using a road foreman of engines and a trainmaster, did the same work within the Hours of Service Law that the four-man union crew had done before.

Then one day I found myself at Silvis in the superintendent’s office. “There’s a train at Peoria ready to come to Silvis, but no crew. How about popping down there and bringing it up here?” So, a young engineering department guy and I drove the boss’s car to Peoria, where we found a nice 75-car train ready to go. But nobody was there to drive the car back.

Yep, I ran and he drove, watching me by the crossings. No problem.

Strike duty memories were never pleasant, but the Rock’s were worst of all — it was all for naught. Neither management nor labor won that one.

We all presided over the death of the Rock Island. R.I.P.

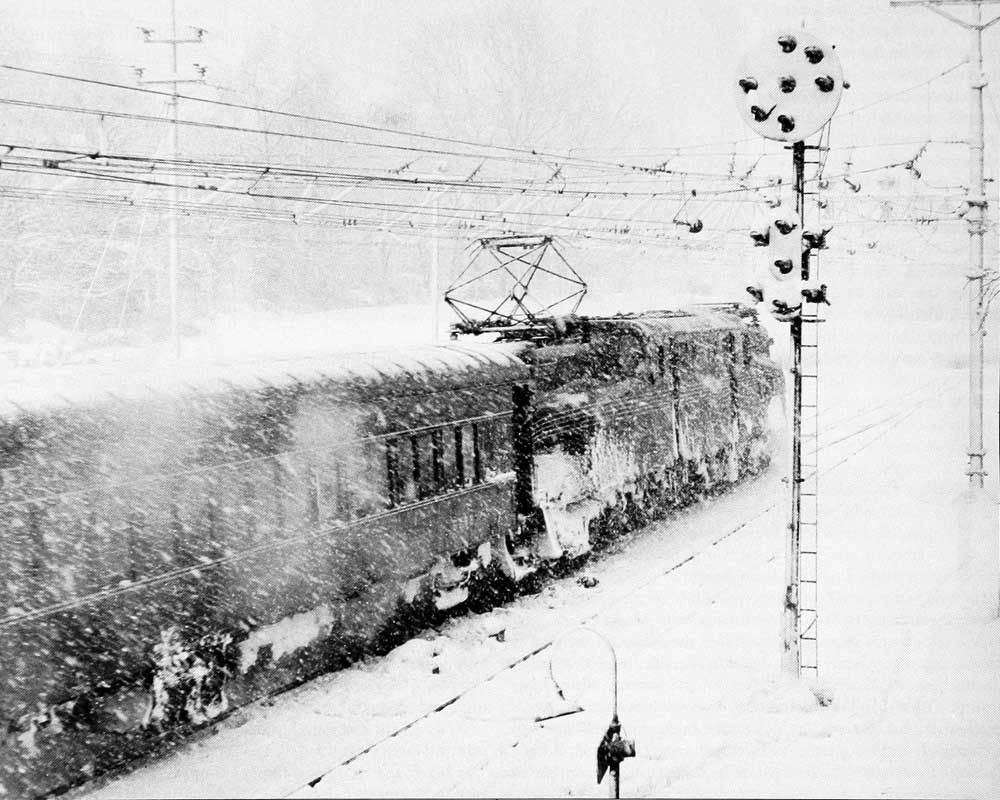

Interesting. My photo of RI 676. I ran a switch engine around the Quad Cities during the strike. After a few days, it wasn’t much fun.