It could have been a Trains News Wire headline: “Reading switcher shoves frozen Doodlebug.” You won’t believe the story.

I awoke and gazed out the window of my home in Coatesville, Pa., to see a veritable torrent of fluffy snowflakes falling. They were burying the landscape of my hometown in a wonderland of whiteness. The time was 4:30 a.m., but I was compelled to dress and go out in that mess, for my job was to see that the mail went through, despite the weather.

As a recent high-school graduate, I had secured what was to me a dream job, and a great railroad adventure. I was a Christmas mail-rush helper aboard the Railway Post Office car of Reading Co. trains 701 and 710, which ran from Coatesville to Reading, Pa., and back. This was my second year at this job, which lasted for only 10 days each season. But the postal pay was generous, and total working time each day came to a mere five hours for eight hours’ pay, although I had to spend nine idle hours laying over in Reading. I put those long hours in Reading to good use, however, by watching and studying the many train movements around Reading’s historic Outer Station, which dated from 1874 and stood in the center of a mainline wye track arrangement.

Bundled up in my heaviest winter garb, I ventured outdoors and challenged the fury of the storm, quickly noticing that the wind had churned up a three-foot high snowdrift across the street in front of my house. I began to walk the five blocks to the Reading’s Coatesville depot, not anticipating the unusual situation I would find there. I trudged through deep snow along the Lincoln Highway (Route 30), the main drag through town, where the only traffic was an occasional truck.

Since I resided at that time in a rooming house, I stopped along the way for a quick breakfast at Coatesville’s only all-night eatery, named the Famous Restaurant. Now, in my opinion, the place should have been named Notorious, because its large pancakes were as thick and heavy as manhole covers, or so it seemed. Worse, I had found, sadly, that their chicken dinners were served with beef gravy!

Having finished my heavyweight breakfast, I plodded on westward and finally reached the Reading depot, where stood train 701’s usual gasoline-electric motor train on a siding in front of the station. Then I heard some loud whistling, announcing the approach of a train. Expecting to see a yard switcher, I was surprised to see it was symbol freight train First RW-2, en route from Reading to Wilmington, Del.

A second surprise came as I saw that this train had been ably equipped to battle through the wintry conditions, for ahead of the double-headed class I-8sb Camelback 2-8-0 types was a snowplow to clear the way. I wish it had been daylight and that I’d had my camera handy, because this scene that greeted me would have made a wonderful photo. As RW-2’s red caboose faded into the snowy distance, I turned my attention to the nearby doodlebug train.

The motor car, No. 67 (later 4067), was a 1929 product of the J. G. Brill works in Philadelphia. It was 75 feet, 6 inches long and weighed 80 tons. Its power plant was two Brill gasoline engines totaling 500 horsepower, enough to haul two additional cars. No. 67 had four compartments: the engine-generator section, a 15-foot Railway Post Office compartment, a baggage room, and a coach section that accommodated 30 passengers on black leather seats. The power car pulled trailer coach 90, a relatively short car measuring only 56 feet 8 inches in length, with plush upholstered seats for 73 passengers. Serving the upper half of Reading’s 64.7-mile Wilmington & Northern branch, trains 701/710 provided the line’s only passenger service and attracted very few patrons, their principal reason for existence being the mail contract. Although less expensive to operate than steam trains, these motor trains were proving to be unreliable, with frequent breakdowns that required steam-train replacements.

Standing there in the snowy pre-dawn darkness, the motor train made a pretty sight with its red marker lamps glowing brightly and light from the coach windows casting shadowy forms on the exterior whiteness. As I walked toward the head end, I spied a steam locomotive that seemed to be coupled on. Furthermore, the engines of the motor car were not idling as they should have been. The locomotive was one of our Coatesville yard switchers, class B-9a 0-6-0 No. 1469, with a rear cab (as opposed to a Camelback, common on the Reading) that was tightly enclosed in heavy canvas storm curtains as protection from the weather.

Reading’s largest and most powerful six-wheelers, engines 1451-1470 were built at the company shops during 1916-18. They had 551⁄2-inch wheels, a weight of 169,800 pounds, and a tractive force of 41,695 pounds. The 1469 was among six or so assorted 0-6-0’s that worked Coatesville’s yards and adjacent steel mills. Her regular daytime assignment was the heavy job down at the Luria Brothers scrapyard, a short distance south of town at Modena. Each evening, she also became a pusher engine for the two sections of symbol train WR-1 as they climbed the 5-mile, 1-percent grade when leaving town. But now, the 1469 was being conscripted for what might have been the most unusual job of her long career.

When I approached the 1469 for a closer look, I encountered Sam Rice, train 701’s regular engineer, as he climbed down from the 0-6-0’s cab. Of course, my immediate question was, “What’s going on?” His answer came quickly, conveying the news that motor car 67 had frozen up during the night and could not be started. The exact trouble was in her two fin-and-tube type radiators, which lay flat atop the roof above the engine room. So, the dispatcher in Reading had instructed the Coatesville yardmaster to have the 1469 haul the dead train up to Reading.

Well now, at this news, my excitement knew no bounds as I walked back to my working area in the RPO compartment. Here I was, not only a mail clerk aboard a train, but also I had suddenly become a participant in a most extraordinary emergency train operation. After all, how often would a six-wheeler be called on to haul a passenger train through a snowstorm? More important, could she make it all the way to Reading?

When confronted with a dead motor car, an obvious first choice for the railroad might have been to send a substitute train down the W&N branch, but that would take hours to accomplish. Therefore, the next (and probably better) choice was to assign the emergency job to the switch engine. Moreover, freight RW-2 had just come down the branch with a plow, so the track could be expected to be reasonably clear of snowdrifts.

Feeling glad to escape the weather, I climbed aboard and went to the RPO section. Inside, the train was a peaceful place of bright lighting and toasty warmth. The mail truck soon arrived from the post office, bringing both the mail for the train and the chief clerk, Andy Markowski.

We quickly set to work opening the pouches and sorting the mail. Andy’s job was at the lettercase, distributing letters into many of its 150 pigeonholes. I did most everything else, including tending the door at the train’s 11 station stops. The small, 15-foot RPO section was cramped and lacked a work table, so I had to work on the floor.

As we worked away, a second batch of mail arrived by truck. Most of that load actually was transfer mail from three Pennsylvania Railroad trains on its busy main line through Coatesville. They were 605, a Harrisburg local; train 13 from New York, the Southwestern Mail; and 580, the Southern Express from Erie. Everything on the Pennsy was right on time despite the weather, and all these connections were made reliably every day, something hard to imagine today. In fact, for many decades, this little train connected Pennsy and Reading’s busy mail routes by way of obscure rural towns and villages, like going from nowhere to nowhere by way of absolutely nowhere.

We completed our terminal mail work as the departure time of 6:13 a.m. neared. My great adventure was about to begin! Conductor Oscar K. Halteman swung a grand highball signal with his electric lamp, the soprano-pitched engine whistle emitted two short blasts, and our makeshift train lurched into motion.

We ran only a short distance to clear the siding switch, then stopped beneath one of the towering arches of the Pennsy’s huge stone viaduct that spanned the Brandywine valley. Brakeman Benny Morgan closed and locked the switch, and then we were off and running on the 40-mile journey to Reading. The meandering path of the single-track, cinder-ballasted branch led up the ever-twisting valley of Brandywine Creek, then over the Welsh Mountains for a total of 30.5 miles before reaching Reading’s main line in the Schuylkill valley at Birdsboro. From there, it was just 9.5 more miles into Reading.

Although the usual maximum speed on the W&N was a leisurely 30 mph, the best gait our little six-wheeler could attain was less than half that. I had asked Engineer Sam Rice how fast he could go with the 1469, and he’d explained that a swaying speed of the engine was OK, but if she began to buck back and forth, the danger of a derailment was at hand. So we slogged along at a snail’s pace through the blizzard, the high-pitched whistle wailing for the many grade crossings.

I was enjoying this unusual ride immensely, and we had lots of time to loaf between station stops. Many of these were at lonely countryside road crossings, and I wondered if the men who brought the mail from their small post offices would even be on hand to meet our now very late train. Perhaps they had been informed by phone about the situation. The train made a rather long stop at Elverson in order to add water to the 1469’s small, slope-backed tender, which held only about 3500 gallons.

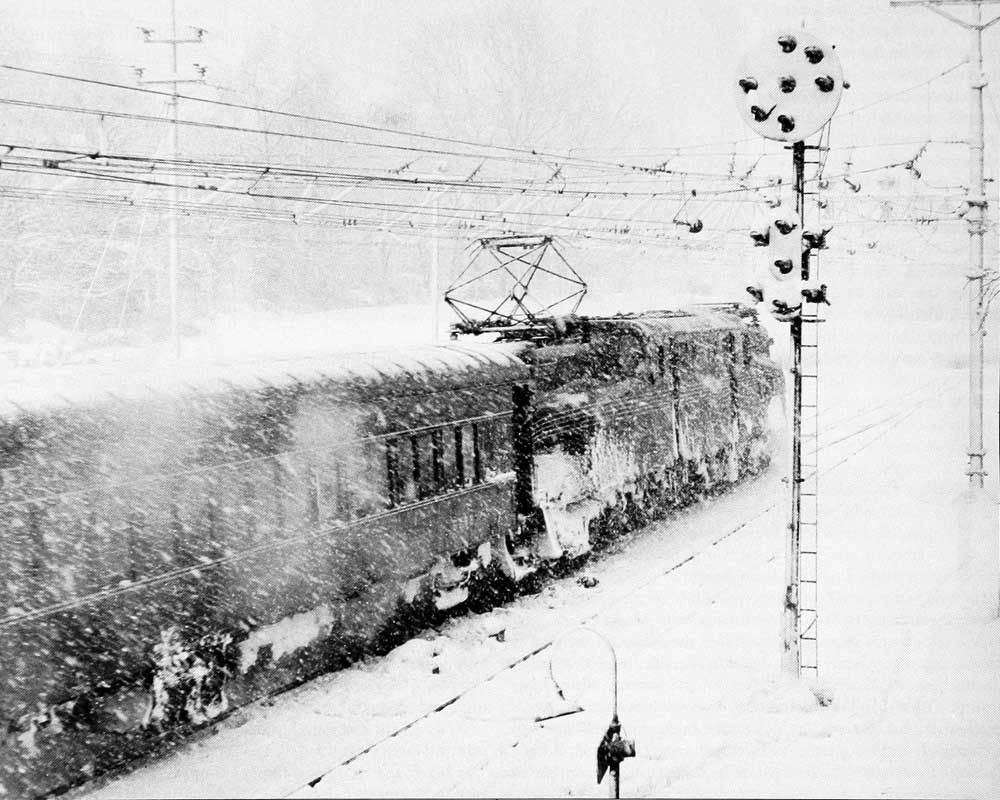

We had departed Coatesville in complete darkness, but as our little engine chuffed on, occasionally bucking small snowdrifts over the track, the half light of a dawning day offered lead-gray skies above the snowy landscape. The cascade of falling flakes finally began to lessen as we neared Birdsboro, where we made another long stop to take on more water.

After Birdsboro, the storm waned as we charged west on the main line. Soon we rounded the big horseshoe curve at Neversink Mountain and Klapperthal Junction, the beginning of the Belt Line freight route around the city of Reading.

We made the Franklin Street Station stop, then went on to the end of the run at Outer Station. The storm had gone its way, and a section labor crew was shoveling the last of the accumulated snow off the exposed portions of the station platforms. We had arrived about 10 a.m., some two hours late, meaning we had covered the 40 miles from Coatesville in four hours, an average speed of just 10 miles an hour.

Our unusual little train arrived on the mainline side of Outer Station, not its usual track. A hostler was on hand to take the consist to the roundhouse, after which the motor car would be headed to the shop. We did not see her again for many months. Later, when that gasoline-electric car was fitted with new Cummins diesel engines, she became quite reliable, with few problems or breakdowns.

Meanwhile, back at Outer Station, our train crew regularly took the equipment of train 701 on to Lancaster as train 901 via the Reading & Columbia Branch. Hence, upon our arrival at Outer Station, there was a steam train waiting to substitute for the disabled motor consist. The locomotive was the 579, an L-3se Camelback Ten-Wheeler, and the consist was a combine, a full coach, and a baggage-RPO mail car with a 30-foot mail section staffed by two regular clerks and a Christmas helper.

That afternoon, for our return trip, we got that same consist. Oh, happy day! I was overjoyed to have 30 feet of working space and a nice large work table. For me, that was sheer luxury after working on the floor in the 15-foot compartment of the motor car.

Memories of that highly unusual run through the snowstorm of more than six decades ago remain strong after all these years, reminding me of how the resourceful Reading Company acted to solve a problem.

Bert must have just moved form his maternal grandmother’s house at 547 Chestnut St. to the boarding house a block away at 118 N. 5th Ave.

Some links:

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Pennypacker-271

https://trn.trains.com/news/news-wire/2009/04/bert-pennypacker-longtime-trains-author-dies

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/GHJX-C5K

Love this story, and if it happened to me, I’d have memorized every detail, too!

Our son lives out in Elverson now, and while that Chester/Lancaster/Berks Counties area has gentrified slightly, the countryside still looks much the same. The tracks are gone now, but much of the station complex in Elverson remains and has been restored for other purposes.

Great story and written like I was there on that snowy day.

Thanks Bert for the memories!

Jerry