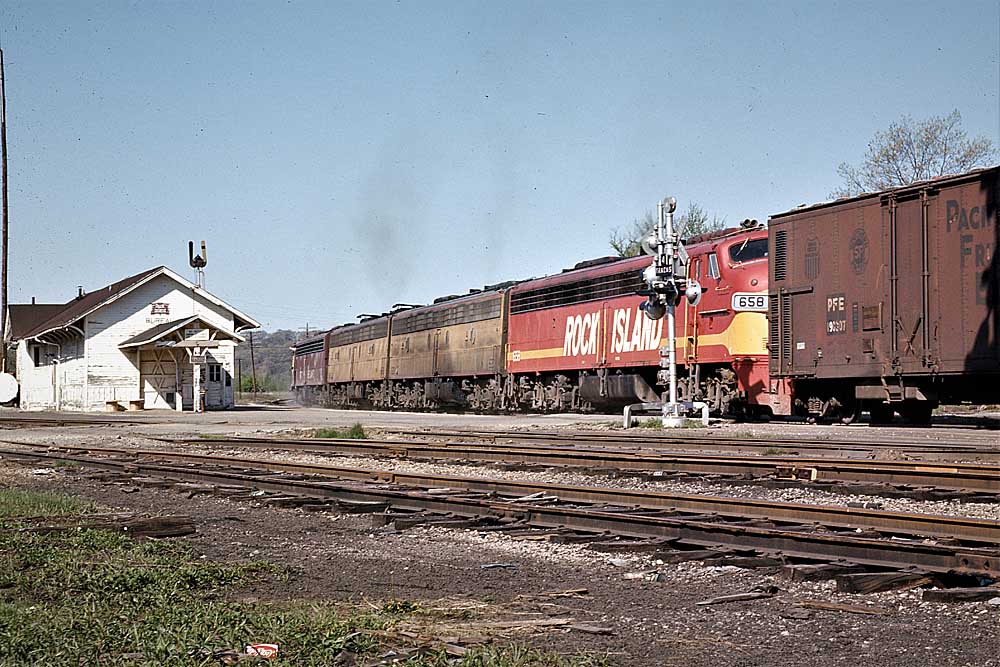

Rock Island perishable traffic: One thing you learn quickly as a new railroad employee is that if you can hold a regular job, it’s because nobody else wants it. In 1973 Rock Island perishable traffic stopped icing at Silvis, Ill. This coincided with Pacific Fruit Express’s exit from the iced reefer business and represented the beginning of the end for shipping perishables by rail.

Several years before the Rock had removed every other track in the receiving yard and, since this left room for a road between each track for the carmen to drive down and bleed off the brakes on an inbound train quickly, it markedly sped up yard operations.

About that time, they removed an additional track between what had been No. 1 track and No. 3 and paved a broad road between No. 1 receiving and what then became No. 2 receiving. This gave mobile icing equipment easy access to inbound reefers needing service but, with the cessation of iced reefer tariffs (and hence, the end of the business), radical change came to the way Rock Island perishable traffic was handled. I shouldn’t imply it had disappeared entirely; it’s just that it now moved in mechanically refrigerated cars and, to a lesser extent, refrigerated trailers.

This reformation led to the abolition of some jobs and the bulletining of several new “Perishable Protective Service Inspector” (PPSI) jobs for clerks. Since nobody wanted one of the afternoon jobs — 3 to 11 p.m. — I became the successful bidder. Thus began my sojourn in the world of “piffees, spiffees, and youpiffees” (referring, of course, to PFE, SPFE, and UPFE reporting marks, the latter two referring to Southern Pacific and Union Pacific). The other outside inspector’s job was bid-in by Ned Loetz. He had enough seniority to easily hold other jobs but the hours and days off suited his needs at the time. The inside inspector’s position was taken by Gary Sager, who had also had considerable seniority but took the inside inspector’s job for the same reasons as Ned. So it was, then, that “Nedly” and “Sagey Baby” became the principal players in this comedy.

Six-Ring Shanty

Six-Ring Shanty was as advertised: about 20 feet square and covered on the outside with that fake brick embossed tarpaper once so popular. Inside it was pure railroad.

All it contained was a desk by the front corner windows for the inside inspector, a desk for the switch tender stationed there, a second desk for the outside inspectors, a small bathroom, a few lockers, and, for heat, an oil-burning “cabin” oil stove identical to the ones in cabooses. It was all on a plain concrete floor that once had been painted.

The walls had also been painted some unidentifiable color in the distant past but now had a uniform, thick coating of yellowed nicotine. It sat at the west end of the receiving yard where the inbound trains arrived and rear-end crews got off. The inbound waybills and list were given to the inside PPSI and the crew waited for a ride to the hump yard office.

The inside inspector went through the waybills and lists to identify cars needing the services of the PPSI department. Waybills for shipments moving under perishable tariffs could be quite complicated. Shippers specified what temperatures should be maintained, if ventilation or heater service was necessary, and parameters for this and a host of other conditions. (For additional detail, I recommend the comprehensive 1992 book “Pacific Fruit Express,” by Robert J. Church, Bruce H. Jones, and Anthony W. Thompson.)

When he was done, Gary gave us a copy with perishable cars marked and what needed to be done to them. The lists and waybills then went to the yard office via pneumatic tube.

The Silvis Shuffle

Now seems to be a good time to say a few words about Kelly Yard. Its primary purpose was to classify eastbound Rock Island perishable traffic for connections in Chicago. Very few westbound trains were classified there. Number 93 (the “Piss Cutter”) from Peoria and No. 61 to Cedar Rapids that usually originated at Silvis were about it, although local business from the Quad Cities could go in any direction and thus would add to the westbound flow.

On the other hand, every eastbound went over the hump. The cars were classified for eastern connections and, since most of the eastern carriers had cutoff times to make their eastward departures between midnight and 8 a.m. and to save on per diem, afternoons at Silvis could be a bit – well, let’s just say chaotic.

Most of the eastbound Rock Island perishable traffic arrived on three trains. The “02” was the biggest source, as it was the connection from Southern Pacific at Tucumcari, N.M.., and could still, on occasion, run in two or even three sections (O2A, O2B, O2C, etc.). Number “44” was the connection from Union Pacific and could also operate in more than one section. The tail-end Charlie was 62 from Cedar Rapids, which could have a smattering of Iowa meat traffic and potatoes from the Northwest.

Usually, these arrived in the late morning or early afternoon. But if things weren’t going well (which was most of the time), the later they arrived the more pressure existed to get them switched for eastbound departures. Which is why, most of the time, Ned and I were busy the first two-thirds, if not all, of the shift.

As a result, there could be considerable pressure to get things done in a hurry on newly arrived eastbound trains. Since nothing could happen until the Perishable Protective Service released the train for humping, quite a few impatient official eyes could be on the “Outside” (i.e., Ned and I) PPSI clerks. So…

Nedly and I To the Rescue

Our principal tools were three well-worn (read: battered) vehicles. All were painted in a shade close to reefer orange with red-and-white “Rock Island” heralds on the doors. One was a plain Chevy pick-up. Another was a small Ford tank truck for diesel fuel. Finally, we had a lift truck on its last legs.

Between the cab and the stake bed was a hydraulic lift. We used it to gain access to the roofs of old ice-type reefers to change heaters or adjust the vents (ice hatches to the un-initiated). Its platform had ramps on either side that could be let down so you could easily walk directly onto the car top.

If there was nothing pressing at the beginning of the shift, we would go over to the heater storage cars (five or so of the old General American meat reefers) where we would refuel (methyl alcohol) a supply of heaters and load them on the lift truck. The general idea was that Silvis was the point where heaters coming from the west (PFE, ART, Burlington Northern, Soo Line) were removed and replaced by heaters appropriate for their eastern connection (Grand Trunk Western, Merchants Despatch, Penn Central, Chessie System, or Erie-Lackawanna).

Ninety percent of these heaters were of the Preco type, meaning a large, round, 5-gallon fuel tank with a burner resembling a tomato juice can but larger on top. They also included an adjustable thermostat on the top of the tank along with a gauge for the fuel. Also mounted on the side of the tanks were two spring clips for anchoring the appliance to the floor.

Fully fueled, they probably weighed 60 pounds or so and had a bail on top to carry them. We carried a sheet steel “paddle” that could be inserted into the side of the burner to extinguish it, and lit them with long handled “strike anywhere” matches.

Perhaps some examples would be the easiest way to give you the big picture. Let’s start with “02A(date)” just arrived on “No. 1 receiving” from Kansas City and Tucumcari with, say, 82 cars, 67 of which are mechanical reefers and the remaining 15 are refrigerated trailers on flatcars.

Ned and I waited on Gary to finish with the waybills and give us a copy of the “list” (a printout of the train consist) so we can go to work. Since this will all be mechanical reefers (piffees, spiffees, and youpiffees) or trailers, we’d take the small tank truck. It’s necessary in case any of cars are low on fuel.

The rule of thumb is that the reefers’ gauges should show a minimum of half full and, if in doubt, fuel them. If we did have to add some, the amount was noted on the list to billed to the shipper later.

Usually, the carmen already had the train blue flagged by the time we came alongside to work from the caboose forward. We verified the car initials and number and checked a) the temperature reading on the car thermometer, b) noted that the refrigeration unit was working, c) saw that the thermostat was set to the temperature noted on the list and made sure the thermometer was close to the specified temperature, and d) it had at least a half-tank of fuel.

If any were found not running, we tried to get them going. We always carried a couple cans of ether in case the recalcitrant engine needed a little help getting started. If we couldn’t get it going, we’d call Gary on the radio and notify him of the car initial and number so he could tell the hump master and have the car sent to the RIP track.

Trailers were a horse of a different color. They seemed to be more troublesome than the cars and there was a bigger variety among them, even if they were the same manufacture. The fuel tanks might have filler spouts on both ends or only on one end.

It was one of these with gauges on one side only that taught me there was more than one way to build a flatcar. Ned and I had split up, so I was by myself. The trailer was by itself on a PFE flatcar. Although I wasn’t happy about having to crawl under a trailer, I soon learned worse could be in store. It turns out that when I swung my leg over the center sill and expected it to land on something solid, there was nothing there! My leg went down all the way to my crotch and, in this semi-split position, it wasn’t easy to get it back up. Painful it was. It turns out the center sill was hollow on these cars with only a bottom web down below. After that, I kept a close lookout for these cars!

Usually though, when we radioed Gary that we were done, within a few minutes the hump repeater signals would change to green and the former train would begin its slow journey up to the hump crest to dissolve into new parts for other consists headed for a variety of places.

Fascinating story.