I sense my mother going down the hall to the kitchen; the light come on, and I can hear her packing his lunch. I listen as the sounds float down the hall. Around the corner at the top of the stairs, the soft whump of the refrigerator door, the tin clank of the breadbox as the lid snaps shut, the rattle of the sliver in the drawer as she digs out a knife. The stairs squeak softly as he comes back up. He closes the bedroom door before he turns on the light so it won’t wake me up.

I fall back to sleep, but soon I am wakened by their voices. I turn and look through my bedroom door at his silhouette near the top of the stairs. His white railroader’s cap stands like a beacon on his head. The lunch bag, dwarfed by his fist, hangs limply at the end of one arm. His broad shoulders bend slightly as he leans over, puts his other arm around my mother’s waist, and gently kisses her goodbye. He turns and as he descends the stairs he softly whispers, “Bunce is the engineer. I’ll be home by noon.”

I hear the whine of the starter on the old Steward truck. It coughs and fires. The headlights blaze against the white clapboards of the neighbor’s house across the street as he eases it out of the side yard. A bright square of light strikes the wall above my head and races around the room only to disappear as the truck passes the front of the house. The rumble of the exhaust rises to a crescendo and falls, starts again but before the peak is reached the second time the sound fades into the northern Pennsylvania darkness. I fall back asleep. He’s off to Ridgway, where a hulking Pennsylvania Railroad 2-10-0 is waiting for him.

Next morning, I could barely hear the whistle as it echoed up the valley. He had taught me to listen for it, and by now I was able to tell by the loudness of the sound if it was for the crossings at Mohan Run, Daguscahonda, or Silver Creek. The warm morning sun began to dry the sand in the sandbox where I was playing, when I heard the second whistle and knew they were passing Daguscahonda. I wondered how he could tell who the engineers were just by listening to the whistle. It must be a heavy load because they are taking a lot of time to pull the hill. “Listen,” he had said, “if you can hear the individual chugs there is only one engine on the head end, but if it gets all mixed up so you can’t count them, it’s a doubleheader.”

I get out of the sandbox as the train whistles for the Silver Creek crossing. The exhaust is a faint roar as I hurry down the lane to watch them come around the bend and past the brickworks. The lane ends at the top of a deep cut where you can look nearly straight down 60 or 70 feet past a huge rock to the track. Looking west, you can see the tracks where they cross a long fill and swing to the right around a bend to disappear behind a low, brush-covered hill. Elk Creek winds to the left of the track. There are no trees on this side of the creek and none on the side of the track, either. Brush fires have reduced the vegetation to huckleberry bushes and a few juneberries.

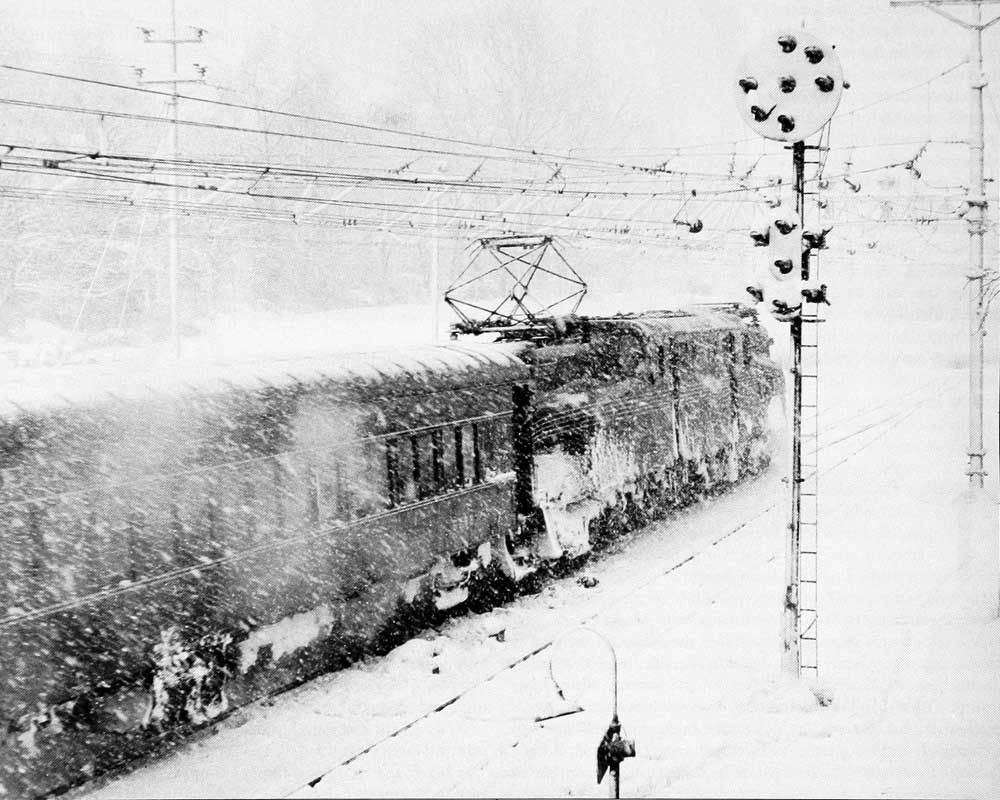

At first the black cloud seems so thin that you can see the blue sky and the tress on the hillside right through it. The throbbing of the exhaust sounds like the distant roll of thunder getting louder as the black cloud looms nearer and nearer. Suddenly the cloud shoots skyward in a violent plume, followed by the rapid staccato of the exhaust, as one of the engines loses traction and starts to slip. The sound stops abruptly and starts again, much slower than before. Slowly at first, and then more rapidly it picks up the rhythm again.

From behind the hill the black cloud creeps forward and its base splits into two scalloped plumes that point, like long tapered fingers, toward the ground. The white of the headlight flashes through the bushes on bottom of Huckleberry Hill. The sound of the exhaust advances in a giant leap, as the lead engine rounds the bend. It is quickly followed by another leap, as the second engine emerges from behind the bushes. The saw-toothed roofs of the brickyard are quickly hidden from sight as the engines cut across the fill and head for the deep cut beside me. The young oak sapling I’m leaning against starts to vibrate, and the ground under my feet starts to shake.

There are no heads poking from the cab windows – those firemen are too busy for sightseeing. No time to wave to a kid along the track now. I hold my hands over my ears to shut out the awful cadence as the two locomotives pound their way through the cut below me. The black smoke blots out the sun, and I quickly cover my head with my arms to keep the cinders out of my hair, trying at the same time to keep my ears covered. I nearly jump out of my shoes as they whistle for the crossing at Ritter’s Mill. Count the cars: One, two, three … Clunk-clunk, clunk-clunk, the wheels of the hopper cars slap the joints between the rails. It’s an iron ore train heading from Erie to Harrisburg. As the sound of the doubleheader fades up the track toward town, the sound of the car wheels seems to get louder.

Down the valley, a second black cloud is growing. The pushers will be here pretty soon. The rhythm of the wheels increases ever so slowly, and the lead engines climb over the Eastern Continental Divide. Down the valley, where the pushers are now, it is nearly a 2 percent upgrade, but by the time they get to town it will be nearly level. Another mile and it is downgrade for more than 180 miles down the Susquehanna River valley to Harrisburg.

As the first pusher rounds the hill, I can see his white hat sticking out the cab window. In a second it is gone. The first pusher is right below me now, and I see him step foot treadle and heave a shovel of coal through the fire door. As he turns back for another shovelful, he looks up past the canopy at the back of the cab. He spots me standing at the top of the hill and waves the shovel. As I wave back, I wonder why he turns back toward the cab. My question is answered in an instant as the white blast of steam pours from the whistle. Whoop-whooo!

I cover my head from the cinders and run as fast as I can for home. Hope she didn’t hear the extra whistle, ’cause I’m not supposed to be back there by the track. I sneak behind the greenhouse and through the alley between the neighbor’s garage and the shanty. Made it, back to the sandbox and she didn’t miss me.

Great story! Just one of the many reasons I like this magazine.