Photo by C. K. Marsh Jr

Downhill skiing buffs immediately think of the winter vacation destination (and site of the 1960 winter Olympics) in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains when “Squaw Valley” is mentioned. More than 50 years ago, the name Squaw Valley came to the mountains of Western North Carolina under entirely different circumstances.

To set the stage, I was a young transportation professional working for Tennessee Eastman Co. at Kingsport, Tennessee, in 1963. The plant was, and still is, the largest chemical plant in the southeastern United States. Tennessee Eastman had started shipping trailers on flatcars on a newly launched Southern Railway dedicated piggyback train. Train 120 left nearby Holston promptly at 6 p.m., six nights a week with chemicals, fibers, and plastics destined for the New York metropolitan area and New England. It crossed the southern Appalachian Mountains during the night and connected with a northbound piggyback train out of Atlanta at Spencer, North Carolina. It was my job to plan loads, assemble the necessary trailers, and get them the 7 miles to the Holston Ramp in time for the 6 p.m. departure.

Southern applied the name COMAR, for COordinated Motor And Rail, to this service. D. W. Brosnan, the road’s president at the time, took a personal interest in COMAR service. He reviewed results each morning. Woe to the trainmaster, road foreman of engines, assistant division superintendent, or superintendent whose operation failed to make schedule or precise connections. As a result, a supervisor was on hand every night at Holston to see that 120 departed on time. He also rode many of the trains to ensure that good dispatching and aggressive crew operations produced the necessary terminal-to-terminal times.

The local on-site Southern official was Sam Sheriff, president of Sheriff, Inc., a non-union affiliate that did switching for Tennessee Eastman and unofficially managed the Holston Ramp. One night Sam and I decided to ride the COMAR from Holston to Asheville, a 129-mile, five-hour schedule. His assistant, Billy Gilmer, would drive over to Asheville and bring us home.

It was a cool evening in September when we climbed aboard F3A 4129 and left, on time, for our rush to Asheville. With two visitors aboard, the head brakeman dutifully retired to the trailing F-unit cab, leaving Sam and me with the engineer and fireman. At nearby McCloud, in a cloudburst, we went into the hole to meet Extra 4198 West, a set of five F units with more than 100 coal empties. Otherwise, we made a nonstop run the entire distance. With a favorable signal indication, we joined the Knoxville–Asheville main line at Leadvale, Tennessee. From Newport, Tennessee, the line follows the French Broad River for 65 miles, rarely more than two car-lengths from the river. This is remote country, with rarely a road or house to break the forested mountain darkness.

It was well into the night beyond Newport when our headlight illuminated a dazzling white area just as we started around a right-hand curve. It looked like someone had taken a bulldozer and pushed back the trees some yards and painted the whole area a spectacular snow white. “What happened here?” I asked. Above the steady drumbeat of the F units, Sam replied, “I’ll tell you the story on the way home. This is ‘Squaw Valley.’”

As the story went, Knoxville Division crews were based at Knoxville and ran to their away-from-home terminals, in this case Asheville. One of the engineers had a Cherokee Indian girlfriend in Asheville. When he caught a run to Asheville they would meet and spend the layover time together. Such was the case when, one evening earlier in 1963, he was called to run back to Knoxville. Both he and his girlfriend were well lubricated, but he took the call. In their alcohol-induced stupor, they decided to make the trip together.

This was at the time when President Brosnan had decided to arbitrarily, by attrition, eliminate firemen from diesel locomotives. After a legal battle, the courts had ruled that the Southern could not abdicate the union contract, thus forcing the company to fill all the fireman jobs that had come open after several years’ attrition. Brosnan, true to his uniquely aggressive personality, decreed that new-hire firemen would conform to five basic requirements: 1) they could only be minorities; 2) they had to be capable of climbing into a locomotive cab and sitting there; 3) they had to be illiterate; 4) they were not allowed to ever touch any of the operating controls; and 5) they had to be more than 65 years old.

The intoxicated engineer and his “squaw” had such a fireman on board. The code of silence among train crews was applied. The head brakeman, seeing the situation, managed to get the impaired crew off the ready track, coupled to their train, and the air pumped up. After lining up the switches, he quietly moved to the trailing F-unit cab.

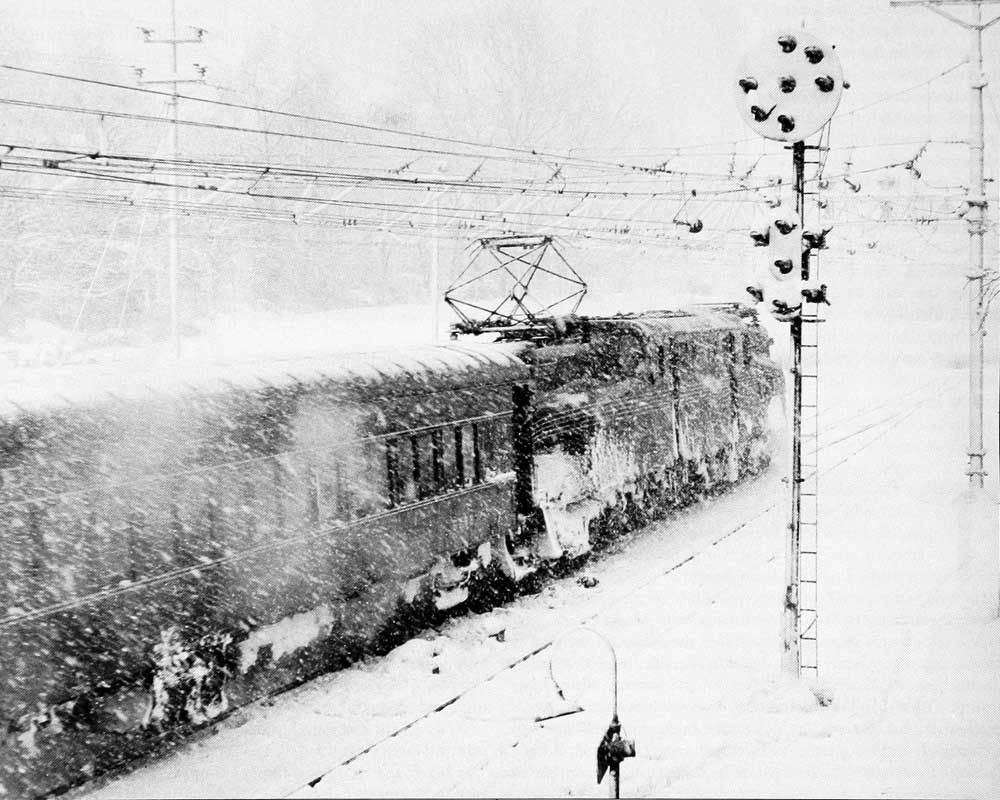

Evidence later showed that, after the engineer released the brakes and got his train moving, he never again made a brake application. Over dozens of descending miles, the train’s speed gradually increased. Finally, some cars back in the consist, including two covered hoppers loaded with flour, turned over on a curve. The flour billowed from the ruptured cars in every direction, coating the area in faux snow. And so the spot became known as Squaw Valley.

When supervisors and emergency crews finally reached the remote site, the engineer was still aboard with his girlfriend. True to form, Brosnan fired the Asheville line’s supervisory personnel, despite the fact that his fireman policy was most likely a direct contributor to the incident.

This all happened a half-century ago, but railroad names, even unofficial ones, have a way of hanging on. I wonder if the Norfolk Southern folks who run the line today still know about Squaw Valley?

First published in Spring 2013 Classic Trains