Is there a more dignified railroad name than “Lackawanna?” Certainly, Lackawanna history evokes many images. In the days of steam, the name meant meticulous track supporting well-proportioned, dual-service “Pocono” 4-8-4s, hefty hogs in the form of three-cylinder 4-8-2s and ponderous 2-8-2s, speedy commuter 4-6-2s, and gorgeous 4-6-4s that even long-time Trains Editor David P. Morgan considered among the prettier of any roads. After dieselization, bulldog-nosed EMD’s in the maroon and gray of Hoboken-based Stevens Institute of Technology rolled the trains alongside the most powerful locomotives of the 1950s: a dozen 2,400 hp Fairbanks-Morse Train Masters. A pre-World War I ultra-modernization of the physical plant shortened the already shortest route between Hoboken, N.J., and Buffalo, N.Y., to 395 miles by building the largest reinforced concrete railroad bridges and line relocations North America had seen. Just after the 20th century began, Lackawanna gave birth to one of railroading’s most famous advertising icons: Phoebe Snow.

The collection of companies that became the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western has one member that predates the start of American railroading: the Hoboken Ferry Co., which began in the 1770s. Among its principals was Col. John Stevens, who in 1825 operated a steam-powered vehicle on a circular railway on his Hoboken estate. Separately, the Morris & Essex in 1835 began laying rails between Morristown and Newark in its namesake counties, then on to Hoboken to the east and Phillipsburg, N.J., on the Delaware River, to the west.

It was iron and coal that lured George W. and Seldon T. Scranton from Oxford, N.J., to Slocum’s Hollow, today’s Scranton, Pa. While canals were common, both Scranton men were proponents of rail to reach distant markets. They looked north to sell rail as a mode to the then-building Erie Railroad, forming the Ligett’s Gap Railroad to reach the Erie at Great Bend, Pa. Its first train ran on Oct. 20, 1851, but by that time the company name had been changed to Lackawanna & Western.

The Scrantons purchased a charter for the Delaware & Cobbs Gap to build south to the Delaware River, with future hopes of reaching tidewater markets and New York City. In 1853 these two roads merged to form the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad.

Coal and iron began to flow from the Lackawanna valley. Enter Moses Taylor into Lackawanna history, president of the National City Bank of New York, who invested heavily in coal lands in the valley, chartering and financing the Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad to tap the Wyoming valley coalfields west of Scranton. Taylor joined the Lackawanna’s board in 1854. He invited Sam Sloan of the Hudson River Railroad to join the DL&W board in 1864; Sloan became president in 1867. Taylor rescued the DL&W during the depression of the 1870s by purchasing enough stock to thwart a takeover by Jay Gould of the Erie. Gould had been building the New York, Lackawanna & Western between Binghamton and Buffalo with the intent to lease it to another Gould property, the Wabash. With Taylor holdings, DL&W leased the NYL&W, thus completing a Hoboken-Buffalo main line.

To reach the Hudson River, DL&W leased the Morris & Essex in 1868. The east end of its system was secure in Lackawanna history.

The legendary Sam Sloan started his working life in an import business on Cedar Street in lower Manhattan. He grew to become a partner and began buying railroad securities, owning enough by 1855 to win a seat on the board of the Hudson River Railroad, and later became its president. After Commodore Vanderbilt got control of the HRR, Sloan declined the presidency to become a railroad arbitrator, which is how he met Moses Taylor.

Sloan’s 37-year presidency of DL&W gave the road steady and consistent direction unrivaled in Lackawanna history. He kept the physical plant and equipment in good shape and sought to develop distant markets for coal. As a financial man, Sloan invested in several roads and held official positions on many while leading DL&W. Among them: International-Great Northern in Texas, Michigan Central, Pere Marquette, and a predecessor of Green Bay & Western. Coal from the DL&W was shipped from Buffalo to Green Bay by Lackawanna-owned Great Lakes boats.

With some of the richest coal holdings and a well-run railroad, DL&W was wealthy and healthy from the 1880s into the 1930s. Indeed, it was one of the original 11 companies in 1884 that made up what would become known as the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Sloan in his lifetime had been a president or an officer of more than 30 railroads.

Lackawanna history defined by its leaders

The personalities of its presidents seemed to define the DL&W. Sloan was quiet and secretive, and financially efficient, although he permitted few trains to run on Sundays. He was determined to expand DL&W into more than a regional coal road. After Sloan’s retirement in 1899 at age 82, Lackawanna directors found William Truesdale, in the top job at Minneapolis & St. Louis and previously a vice president of the Rock Island. He was DL&W’s first president who was a railroader rather than a financier.

With cash in the coffers and steady revenues, Truesdale set out to turn the DL&W into a super railroad. He replaced management, ran more Sunday trains, and upgraded rail, bridges, and roadway to improve schedules. He created world-class engineering projects such as the series of lofty reinforced concrete viaducts and massive fills and cuts on the New Jersey and Nicholson cut-offs. He separated nearly 100 road grade crossings in the 38 miles between Hoboken and Dover, N.J., while adding track. DL&W’s masonry passenger stations and interlocking towers were works of art.

A 1903 advertising campaign created a lovely character “. . . whose gown stays white, from morn’ ’til night, upon the Road of Anthracite.” Clever jingles and constant press releases turned the fictitious Phoebe Snow into a popular celebrity with merchandise to match. One contemporary newspaper claimed that 10,000 people had come to the Binghamton station to see her.

Lackawanna burned what it hauled — anthracite, which was virtually smoke-free. With clean rock for track ballast in an era when most mainline railroads used coal cinders, Lackawanna heavily promoted its dust-free ride using “celebrities” such as Phoebe Snow and Mark Twain. The anthracite burning ended with World War I when the Navy and merchant ships needed the smokeless fuel to help them avoid German U-boats.

During and after the war, Truesdale wrestled with declining coal revenues owing to the 1906 Hepburn Act, part of Teddy Roosevelt’s aim to curb transportation profits. To comply with its Commodities Clause, DL&W in 1913 created the DL&W Coal Co. That fix lasted until 1921 when a new provision in Pennsylvania’s constitution forbade a railroad from mining or making articles for transportation. Truesdale transferred DL&W mining operations to Glen Alden Coal Co.

In 1925, John M. Davis replaced the aging Truesdale. Davis was also a railroader, having been superintendent of the Erie and vice president of Baltimore & Ohio. He had the energy to complete Truesdale’s projects such as the suburban electrification to Dover and adding track while developing efficient motive power. He also had the wisdom to guide DL&W through the Great Depression and to compete with motor vehicles. Davis retired in 1940 having done a credible job.

Postwar roller coaster of Lackawanna history

In 1941 William White joined the Lackawanna, having been vice president at Virginian Railway after 25 years with the Erie. While White’s DL&W enjoyed traffic increases because of World War II, he also had the burden of dealing with rapidly increasing property taxes in New Jersey. White led DL&W into dieselization. He inaugurated the all-streamlined Phoebe Snow in 1949, then left in ’52 for the New York Central presidency.

To replace White, DL&W promoted Vice President of Operations Perry M. Shoemaker, a Yale man and the first college graduate to run the company. Shoemaker’s early railroading was with the Erie, then the New Haven before joining DL&W in 1941. Shoemaker was a classic president and a hands-on manager. Each morning he wanted to know if the Phoebe was on time, and he commuted to the 140 Cedar Street headquarters in lower Manhattan each morning from Summit, N.J., on Lackawanna electric trains and Hudson River ferries.

Shoemaker dealt with declining coal traffic as homeowners switched to oil heat and property taxes kept rising. He was a visionary in his asking New Jersey to assume the cost of running suburban trains. Then came Hurricane Diane in August 1955, which washed out sections of main line and many bridges in the Poconos and on the Sussex Branch. Repairs took 30 days and more than $8 million ($70 million in 2013 dollars), for which DL&W paid cash.

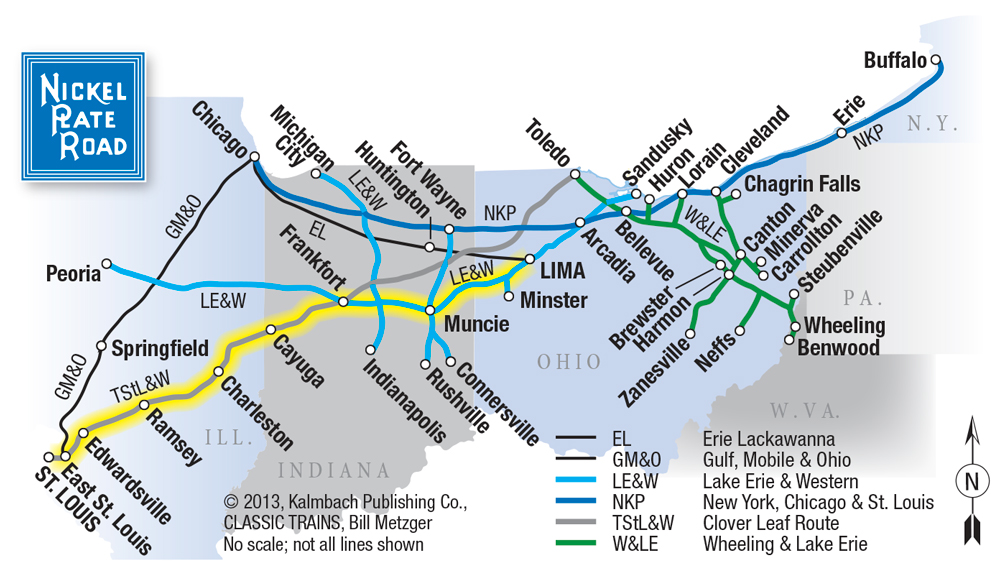

After post-Diane repairs, Shoemaker sought merger. First, he courted longtime Buffalo connection Nickel Plate Road, a move that from today’s perspective was a good end-to-end match. But in that era, NKP was not interested, marrying instead the Norfolk & Western. Shoemaker got favorable terms, however, from the mostly parallel but much larger Erie. After a successful combining of sections of railroad beginning in 1957 — when Lackawanna trains began using Erie trackage west of Binghamton and Erie passenger trains shifted from their Jersey City terminal to Lackawanna’s at Hoboken, the corporations joined together officially on Oct. 17, 1960, with Erie in control.

After 110 years of rivalry and respect, the two roads were one: Erie-Lackawanna, at first with the hyphen. Rather than creating efficiencies as envisioned, however, the merger increased debts and losses. In 1963, former DL&W President Bill White returned, and the new company dropped the hyphen to be Erie Lackawanna. By 1965, EL was profitable and improving. White died in his office in 1967, but by year’s end, EL’s ink was again red.

In 1968 EL merged into Dereco, an entity controlled by Norfolk & Western. Hurricane Agnes in 1972 drenched the Poconos, a catalyst resulting in Dereco filing for bankruptcy. There are legends about EL talking to Santa Fe and Delaware & Hudson about merging, but in the end EL chose to join Conrail, the government-backed combination of several bankrupt roads in an effort to save the railroad industry in the Northeast.

Today the memory and reminders of DL&W remain strong. On the east end, New Jersey Transit operates the Morris & Essex, Gladstone, Montclair, and Boonton branches and has beautifully restored Hoboken Terminal and many stations. Although Conrail abandoned the entire 26-mile New Jersey cut-off, NJT is relaying the eastern 7 miles to begin commuter service to Andover.

Scranton is still the heart of the old DL&W and a hub of Lackawanna history, with Steamtown National Historic Site running steam out of the restored roundhouse. Short line Delaware-Lackawanna puts on a grand show with historic and well-kept diesels hauling freight between Scranton and Portland, Pa., connecting again its namesake rivers. Canadian Pacific owns the main line between Scranton and Binghamton over the majestic Tunkhannock and Martins Creek viaducts. Parts of the “Bloom” are gone, but what remains is operated by short lines North Shore; Reading & Northern; and Luzerne & Susquehanna. While some of the Utica Branch was taken out of service by New York, Susquehanna & Western, the Syracuse side sees mainline Susquehanna freights and occasional CSX trains on trackage rights.

It’s impossible to visit Scranton today without seeing reminders of Lackawanna history. Moreover, among NJT’s many routes, the DL&W lines are the least changed in that train numbers are still in the same series, most of the original stations are still in use, and the Gladstone line still runs with an interurban spirit. While riding in brand-new multi-level cars on concrete ties and welded rail, it’s easy to recall one of the very last Phoebe Snow jingles: “Hello, hello, says Phoebe Snow, as we welcome you to our new show. Steam steps aside, and now you ride, upon a road Electrified.”

Mike,

Great historical information and snapshot of the DL&W as usual!

Brings back wonderful recollections. I grew up in Millington, NJ, along the Gladstone branch. As a young boy, there was still regular freight service, with a National Gypsum plant in Millington reaching and shipping 6-10 cars every other day into the mid 1960s. There was also a lumber yard–Nicholas Thomas lumber–in Millington that occasionally received box cars of lumber. I often rode the electric MUs , and students at Bernards High School in bernardsville who lived in the towns of Far Hills, Peacock and Gladstone received passes for the trains to get to and from school. this was true into the at least the late 1970s when I was a teacher there.

I don’t know how to interpret the term ‘legends’ in the 4th from last paragraph. I can assure you that the Santa Fe did study the acquisition of the Erie Lackawanna. What I never knew for certain was who originally authorized the study. In any case my boss was both in favor of the acquisition and deeply disappointed that he could not get upper management to pursue the acquisition. I think he continued the study after he was told to cease and desist. His plan included the use of the EJ&E between Griffith and Joliet as the primary link between the two properties. The alternative was the old J&NI.

It would have been fantastic, especially if they could have found a way to bypass Chicago to the south.

Ron is correct. Initially the DL’s ancestor Ligett’s Gap RR was a feeder to the Erie, which was 6 foot gauge. Later, when DL headed to NY, first over CNJ and then taking over the Morris and Essex (now NJT’s electrified line) they had dual gauge track. DL eventually went to 4 foot 8 1/2 gauge.

You didn’t mention that the line was 6 foot gauge in its early days.