Strictly speaking, Grand Trunk Western is not a “fallen flag.” GTW still reports to regulators as a separate Class I railroad, but since Jan. 1, 1996, GTW has been submerged in the identity of its parent, Canadian National. These days, operation and management of GTW are integrated with the 2,650-mile former Illinois Central and the 2,850-mile former Wisconsin Central, merged by CN in 1999 and 2001, respectively.

“Grand Trunk Western” was adopted as a trade name in 1923, when four-year-old Canadian National Railways took over the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada but did not want to use its governmental name in the U.S. The GTR, conceived in 1852, had built from Montreal west to Toronto, then east to Portland, Maine. West from Toronto, GTR reached Sarnia, Ontario, across the St. Clair River from Port Huron, Mich., in 1858, and pushed on to Chicago by 1880.

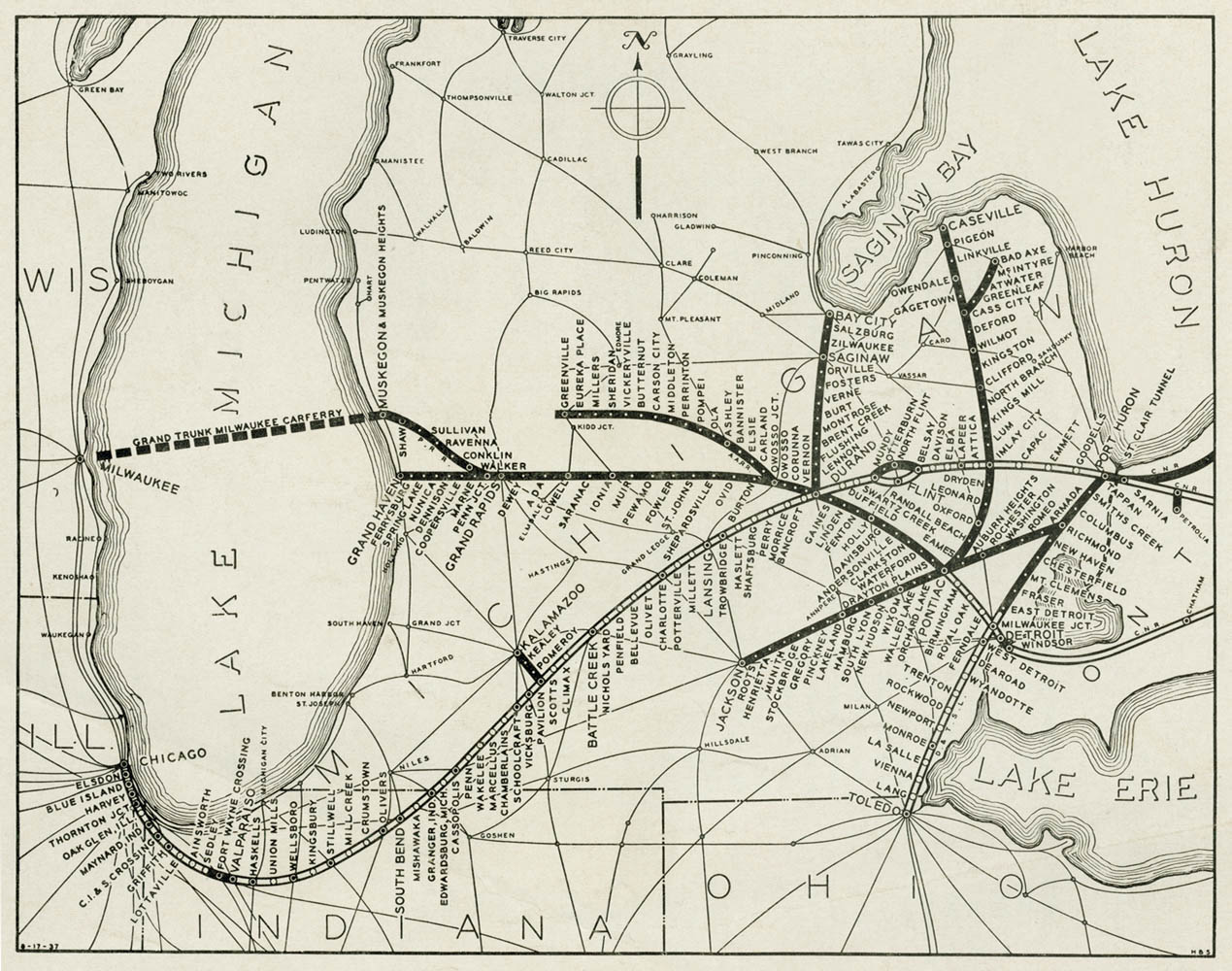

In post-World War II years, GTW operated 967 miles of track, over 850 of them in Michigan. At its hub of Durand, the Port Huron-Chicago main crossed the secondary main that linked Detroit with the Lake Michigan port of Muskegon (which succeeded Grand Haven in 1933). A Detroit-Port Huron secondary main and six branches, the most important of which went to Saginaw and Bay City, completed GTW’s rail map.

A personal Grand Trunk Western history

I grew up near the GTW main line in Lansing, Mich., and as a teenager made frequent trips to Durand and Detroit to photograph the last years of GTW steam after the main line was dieselized in April 1957. I saw CN steam in that era as well, but there was never any doubt of GTW having a separate personality.

In Lansing, the quintessential passenger-train experience was witnessing the 4:30 p.m. departure of train 17, the Inter-City Limited, for Chicago, and there was rarely a school day from 1955 onward when I was not at the depot to do that, and also to ride the switchers around town or listen to the dispatcher’s phone activity in Washington Avenue tower by the depot. Our family often used 17 to Chicago, and since the dining-car crew was accustomed to seeing me at Lansing when the car laid over between trains 20 and 17, we got extra attention. For every customer, the food was great, the portions generous, and the service warm and friendly. There were even uniformed news butchers, who like the diner also flipped back from 20 to 17 at Lansing.

We also used 5 and 6, the night locals which handled Chicago-Lansing and Detroit sleepers, but rarely 14 or 15, the top-line Chicago-Toronto International Limited, because its times at Lansing were not convenient. Until early 1957, the power on 17 was usually a Northern, either one of the 25 Alco U-3-bs of 1942 (6312-6336) or one of the 6 Lima streamlined U-4-bs of 1938 (6405-6410), a different design with 77-inch drivers versus 69 on the U-3-bs. There were only two passenger diesels then, GP9’s obtained in 1954. A 6400 storming out of town past the Oldsmobile plant with 17 remains my iconic memory of steam.

A U.S.-Canada agreement permitted locomotives and passenger cars from either country to operate in the other if the equipment was home in 72 hours. The physical barriers of the electrified St. Clair Tunnel at Port Huron and the Detroit River ferry operation to Windsor, Ont., however, meant that in practice, power didn’t run through until the tunnel was de-electrified in 1958.

At that time, GTW GP9s began handling the through Chicago-Toronto passenger assignments. Power shortages on GTW in 1968-69, then free trade agreements in the ‘70s, brought CN power to GTW, including FP9s on the varnish. CN passenger cars regularly ran between Toronto and Chicago right from the 1923 beginning, except that sleeping cars were always Pullmans (CN operated its own sleeping cars within Canada).

CN was just beaten by Northern Pacific for the distinction of placing the first 4-8-4s in service. NP engines 2600-2611 began coming from Alco in December 1926, while CN U-2-as 6100-6119 first left Canadian Locomotive in June 1927. GTW’s version, U-3-as 6300-6311, came from Alco in July 1927, and was different in appearance from the Canadian engines. It was the U-3s more than any locomotive which set the tone for a separate personality of GTW. The U-3s were transferred to Canada in 1940-41 because of the war emergency (and “disappeared” in CN’s sea of 165 U-2s). They were replaced on GTW by the 25 U-3-bs, which became the road’s virtual trademark. GTW’s U-4-bs were almost identical to CN U-4-as 6400-6404, but a unique smokelifter on the Limas (also later used for a time on GTWs 5 Baldwin 4-8-2s) gave the U-4-bs a distinct look.

Track and operations

The 334-mile Chicago-Port Huron main line was all double track except for 5.46 miles, Valparaiso to Sedley, Ind., where terrain and the Pennsylvania-Nickel Plate-GTW interlocking at Fort Wayne Crossing obliged leaving it single-track. In 1955, much of the line east of Durand was also singled, with CTC.

This was a fast freight railroad with a 60-mph speed limit in effect for decades, and with a marked tendency to exceed even that generous limit (Trains Editor David P. Morgan rode hotshot 490 in the late 1940s and recalled having to drop running times from his article to avoid implicating crews). High standards of track maintenance were always in force. During the troubled 1970s, with national publicity on track-caused derailments elsewhere, GTW used its “GT” symbol to advertise itself as “the Good Track Road.”

Crème de la crème of the fast freights was 492, the perishables train out of Elsdon Yard in Chicago each morning with only a few cars but filled out with refrigerator cars off the Indiana Harbor Belt at Blue Island and the Illinois Central at Harvey (mostly bananas for Toronto and beyond). Its crews were bulletined just like those of passenger trains, and the jobs went to senior employees. The regular man every other day between Battle Creek and Port Huron in the 1950’s was named Kelly, and I recall it was standard for employees to remark, as 492’s U-3-b bore down at 60 mph on the nominal 25-mph Washington Avenue crossing in Lansing, exhaust laid flat and reefers bouncing even on the excellent track, “Here comes Kelly.”

Steam ruled 492 as long as there was any steam on the main line — the U-3-bs did not have the “inconvenience” of an overspeed trip. After mainline dieselization, 492 got three GP9s instead of the two customary on other freights, and when possible they were passenger-geared 4500s and 4100s (83 mph) which had not been available until 1957. The 22 F3As of 1948, which each logged more than 1.5 million miles before being retired in 1971, and the 15 freight GP9s of 1954 all had a top speed of 65 mph.

Of similar stature to the Chicago-Port Huron main was the Detroit Division’s 67-mile, CTC-signaled Durand-Detroit line, double-track the first 27 miles from Detroit to Pontiac. Durand had three wye connections, and interdivisional freight crews ran through between Detroit and Battle Creek and Detroit and Flint, much of the business linking General Motors auto plants. The auto industry, although cyclical, was GTW’s traffic mainstay, and GM its biggest customer (hence its mostly EMD diesel fleet).

GTW operated through Detroit-Chicago Pullmans and coaches, plus three Pontiac-Detroit suburban trains each weekday. Durand-Detroit daytime locals 21 and 56 (remnants of what had been twice-daily Detroit-Muskegon service) saw the last regular revenue passenger operation of steam in the U.S, in March 1960. Shortly thereafter, the Detroit Division also hosted the last regular U.S. intercity mainline steam freight service.

Similarly important were the Port Huron-Detroit-Toledo freight operations (crews changed out) via the 50-50 owned (with Nickel Plate) Detroit & Toledo Shore Line. After Norfolk & Western acquired NKP and Wabash in 1964, N&W considered the Shore Line surplus, finally selling its half to GTW in 1981. Meantime, GTW in 1980 had acquired the 450-mile Detroit, Toledo & Ironton, so the nature of the Detroit-Toledo operation was quite changed. These acquisitions ballooned GTW’s system to its maximum 1410 route-miles.

The west end of the Detroit Division main, from Durand through Grand Rapids to Muskegon, existed almost entirely for the Grand Trunk Milwaukee Car Ferry Co. service across Lake Michigan to Milwaukee, Wis. Until all three crosslake rail freight services quit in the late ’70s, “the Trunk” operated two Muskegon trains each way a day. When the ferries went, the railroad did too, leaving just stubs for shortline operation.

In modern times, GTW had three carferries. A switcher (for ages GTW’s one-of-a-kind 1926 Brill box-cab, retired in 1960) and crew were stationed in Milwaukee to load and unload the boats and interchange with Chicago & North Western and Milwaukee Road. From the 1930s until 1953, Pennsylvania Railroad was involved in GTW’s lake operation, including trackage rights on GTW’s 0.32 miles of track in Wisconsin. All three boats had their superstructures raised in the early ’60s for hi-cube auto-parts cars, but that did not keep the traffic from being diverted to Chicago as interchanges there improved and the boats got more expensive to operate. The Durand extra board protected vacancies on the Milwaukee job, making for an interesting deadhead (usually via Chicago).

In 1971 GTW became the big component of Grand Trunk Corp., CN’s corporate consolidation of its U.S. properties, led by Robert A. Bandeen, a CN vice president. A decade later the DT&I acquisition extended CN to Cincinnati and connections in the South, but deregulation in 1980 had changed the game, and again GTW’s two important attributes were its Chicago route and automotive traffic.

By 1992 every GTW line north of the Chicago-Port Huron main, except the 11-mile branch to Kalamazoo, had been abandoned or sold to short lines. In 1997 GTW sold what was left of the old DT&I south of Diann, Mich., to Indiana & Ohio, so today, CN operates 535 miles of GTW: from Toledo (D&TSL), as well as from Diann and Flat Rock (DT&I), through Detroit to Port Huron and Durand, plus the Chicago main line.

Grand Trunk Western’s last systemwide show of independence from CN was in 1971 under Operating Vice President John H. Burdakin, when GTW departed from CN black on diesels (which dated from 1962 with the GT “noodle”) and chose blue for engines and cars. Since 1996, however, “GTW” has been just small initials on CN-painted rolling stock, essentially marking the end of Grand Trunk Western history.

A very interesting and informative read Mr. Pinkepank. Living in the Mobile, AL area my only connection with the GTW has been the blue GTW switch engines that were assigned to the IC yard here for many years. That yard and the IC/CN tracks in and around Mobile are now operated by the Alabama Export Railroad with CN operations from Jackson, MS stopping at Belt Junction.