Gulf Mobile and Ohio remembered: The “modern merger movement” is often said to have begun in 1957 when Louisville & Nashville absorbed the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis, in which the L&N had a three-quarters ownership. Some would argue that three similar 1947 mergers — Denver & Salt Lake into Denver & Rio Grande Western; Alton Railroad into Gulf, Mobile & Ohio; and Pere Marquette into Chesapeake & Ohio — should mark the movement’s beginning. In all four cases, though, the surviving carrier already had a stake in, or a degree of control over, the “fallen flag.”

Omitting the interruption of World War II, a significant merger occurred just before the first three above, in fall 1940 — the creation of the GM&O itself. Some would argue that GM&O’s creation — a classic “parallel merger” — set the tone for rail mergers in the second half of the 20th century.

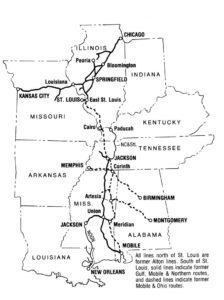

GM&O was formed from two Deep South carriers: 827-mile Gulf, Mobile & Northern and 1,180-mile Mobile & Ohio. GM&N reached from the ports of Mobile, Ala., and New Orleans, north, joining at Union, Miss. (between Jackson and Meridian), en route to the west Tennessee city of Jackson, while M&O, which paralleled GM&N 25 to 30 miles to the east, went from Mobile through Meridian, Miss., and Jackson, Tenn., to metropolitan St. Louis.

Both partners had colorful histories dating to the mid-1800s. As was true for GM&O kept the silver-and-crimson colors of predecessor Gulf, Mobile & Northern’s 1935 stream-liner Rebel (leaving Southern’s Terminal Station in New Orleans, above, at age 10), and applied them to its early diesels, such as 1940 S1 664.

Many railroads, each itself arose from mergers of smaller lines, including logging and narrow-gauge pikes. GM&N’s slim-gauge predecessor, the Ripley Railroad in northern Mississippi, pre-dated the better-known Colorado narrow-gauges, and the same was true for the M&O’s 3-foot-gauge predecessor in southern Illinois, the St. Louis & Cairo. M&O’s tracks north of Corinth, Miss., had been the objective of the opposing armies in the Battle of Shiloh during the Civil War, and M&O suffered severe damage in fighting around Meridian. GM&N was the evolution of several end-to-end mergers and reorganizations of small roads that tapped the hilly, heavily forested areas of southern and central Mississippi. Forest and related paper products would be a system traffic staple for over a century.

The man behind the GM&O was Isaac Burton “Ike” Tigrett (TY-gret), a banker from Jackson, Tenn. He’d been appointed receiver for the GM&N when it emerged from government control after World War I, and his business philosophy was “growth by merger and take care of the stockholders first.” Tigrett surrounded himself with executives who would think unconventionally, rare in the staid railroad industry.

Mobile & Ohio had been in bankruptcy during the Great Depression and was controlled by the Southern Railway. When Southern offered the M&O for sale in the mid-1930s, Tigrett saw an opportunity to protect and strengthen GM&N’s territory and extend its reach to the St. Louis gateway.

Merger and motive power

Toward this end, he incorporated the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio in November 1938, and directed purchase of the M&O, completed on September 13, 1940. His timing was fortunate, for the traffic surge brought on by World War II allowed the new company to prosper beyond anyone’s expectations.

Tigrett was an innovator, with both the GM&N and the GM&O. The merged carrier was the first large Class I road to dieselize, and it made extensive use of gas-electric (later, diesel) motor cars for local and branchline passenger service. Before the merger, Tigrett’s GM&N joined the streamlining trend when it introduced in July 1935 the lightweight, diesel-powered Rebel linking Jackson, Tenn., and New Orleans. Just weeks after the merger, Gulf, Mobile & Ohio upgraded its passenger service with full-sized cars on the St. Louis-Mobile Gulf Coast Rebel, pulled by new Alco DL109 diesels. (As a result, the three pioneer Rebel trains came to be called “the Little Rebels.”)

The new Gulf Mobile and Ohio went to work in 1940 with a fleet of small, aging steam locomotives, dominated by 87 2-8-2s, 61 4-6-0s, 26 4-6-2s, and 26 2-10-0s, none built after 1928. Spurred by a cost-benefit analysis conducted by then General Manager Glen P. Brock, GM&O aimed at an ambitious goal of completely dieselizing by 1950. GM&O beat that by a year, when Mikado 404 tied up on an October 1949 day at Columbus, Miss.

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio’s diesel fleet was almost all Alco. A 6-cylinder 539 engine powered each of the three ACF-built Rebels, and their silver-and-crimson colors were applied to GM&O’s first diesels: the 3 DLs; 4 S1s of 1940; and 12 S2s of ’41-46. The breakthrough for dieselization, in ’46, was Alco’s first fleet of 1,500 hp freighters (55 cabs and 31 boosters) that came to be known as “FAs” and “FBs.”

Tigrett didn’t stop at St. Louis. He had his eye on Chicago, and a golden opportunity for further expansion came in 1943 when the bankrupt Alton Railroad was offered for sale by owner Baltimore & Ohio. The Alton, which B&O had renamed from “Chicago & Alton” in 1931, two years after it purchased the road, had two routes out of St. Louis. The main line, which dated from the 1847 Alton & Sangamon, went to Chicago; the other went to Kansas City.

Enter the Alton

By buying the Alton, Tigrett’s goal of creating a Gulf-to-Great Lakes railroad would be realized; Kansas City was almost an afterthought. B&O’s goal with the Alton had been to break the invisible east-west Mississippi River wall as only the Wabash otherwise did, but this was ultimately thwarted by other big Eastern roads, so with little freight traffic on the Alton, B&O sold it. Gulf Mobile and Ohio’s directors agreed with Tigrett’s plan in early 1945. After some delay by the Interstate Commerce Commission, GM&O and Alton were united on May 31, 1947.

The merged carrier kept the name Gulf, Mobile & Ohio, but Tigrett was savvy enough to submerge “The Rebel Route” slogan and adopt “The Alton Route,” since the Alton was the premier passenger carrier on the fast, competitive Chicago-St. Louis corridor. GM&O also deferred to the Alton’s colors, giving up the silver-and-crimson for Alton’s red and maroon with gold trim, in which even the pre-merger FA’s were delivered. The amalgamation transformed a profitable little Class I serving a Deep South region with an agriculture-based economy into a 2,900-mile trunk line serving Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City. But in many ways Gulf, Mobile & Ohio continued to be “two railroads in one.” The northern region and southern region (or “north end” and “south end”) were different in character, as was their motive power, well into the 1960s.

The merged carrier kept the name Gulf, Mobile & Ohio, but Tigrett was savvy enough to submerge “The Rebel Route” slogan and adopt “The Alton Route,” since the Alton was the premier passenger carrier on the fast, competitive Chicago-St. Louis corridor. GM&O also deferred to the Alton’s colors, giving up the silver-and-crimson for Alton’s red and maroon with gold trim, in which even the pre-merger FA’s were delivered. The amalgamation transformed a profitable little Class I serving a Deep South region with an agriculture-based economy into a 2,900-mile trunk line serving Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City. But in many ways Gulf, Mobile & Ohio continued to be “two railroads in one.” The northern region and southern region (or “north end” and “south end”) were different in character, as was their motive power, well into the 1960s.

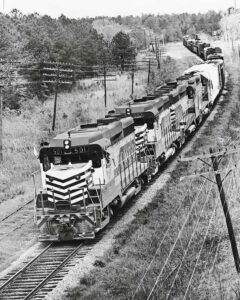

In the South, Alcos reigned supreme, but in the North, there was a mix. While the Alton had acquired 10 S2s and 10 RS1s right after the war for yard jobs and locals, EMDs ruled the road. Alton had inherited two EMC passenger units from B&O, a boxcab and a streamlined EA, and also got seven of the earliest E7s. Orders for F3s (by the Alton, delivered as GM&O) and F7s followed. The fleet totaled 28 F3s and 14 F7s, with 12 F3s (9 cabs, 3 boosters) having steam boilers and being used in both passenger and freight duty. With 34 RS1s, 14 RS2s, and 9 RS3s for local freights, GM&O never owned a Geep until the second generation. As the 1950s waned, broken crankshafts, especially on the FAs, kept workers busy at Iselin Shops in Jackson, Tenn., but officials received no such complaints about the Fs from the former Alton shops at Bloomington, Ill. EMD was offering attractive trade-in terms on its new GP30, so GM&O struck a deal that would, during 1962-65, see all Alco road units (plus the lone Ingalls road-switcher and GM&O’s only Baldwins, a pair of passenger cabs) go in trade for 31 GP30s and 48 GP35s, which rode on the FAs trucks and kept their Westinghouse traction motors. EMD designed the Geeps’ black-and-white livery, as well as the subsequent red-and-white schemes on follow-up SD40s and GP38s.

In the South, the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio main lines navigated a hilly profile and were unsignaled. Although well-maintained, the track didn’t really appear to be that of a Class I railroad. The rail was not heavy, and the roadbed wasn’t immaculately groomed or heavily ballasted. Conversely, the former Alton Chicago-St. Louis main, being a high-speed passenger railroad, had block signals — distinctive B&O-style color position lights, only now finally being replaced. Quietly progressive, GM&O in the 1960’s installed CTC signaling on the Alton and single-tracked it.

I once heard the GM&O favorably described as a “3,000-mile short line,” which the Southern Region surely seemed to be. Despite appearances to the contrary, GM&O was a profitable company, thanks to conservative management and strict attention to customer service.

Even as GM&O modernized, Brock, elevated to president in May 1957, eventually saw in its bigger, parallel competitor Illinois Central the familiar parallel merger “writing on the wall.” So, in the mid-60s, Brock began the discussion process that would, two-and-a-half decades after the Alton acquisition, result in the next merger, IC taking over GM&O. This occurred in August 1972, with IC adding Gulf to its name.

Much of the original GM&O is gone, though not the Alton. Short lines and Kansas City Southern operate some segments in the South, and KCS also has the St. Louis-K.C. line. Most of Chicago-St. Louis belongs to Union Pacific and is being upgraded into a higher-speed passenger route for improved Amtrak service (Chicago-Joliet stayed with IC, now Canadian National). Difficult as it may be to comprehend, Gulf, Mobile & Ohio now has been extinct just about the same length of time that it existed and carved a lasting niche in our memory.

Jackie is half-right; the Alton (while under Baltimore and Ohio’s control) did name the ABRAHAM LINCOLN’s companion train after Lincoln’s sweetheart, but it was ANN RUTLEDGE that received the honor, not NANCY HANKS. The Central of Georgia would in time rectify the oversight.

The management trio of Tigrett, followed by Frank HIcks and lastly by Glen Brock started out as progressive but ended up as being very paternalistic. After dieselizing in 1949, they didn’t keep up with physical plant improvements, information technology, nor management philosophies. Given that much of the GM&O was sold off or abandoned, perhaps it was one railroad too many for its territory.

I was always amused by the fact the Alton had trains named the Abraham Lincoln and Nancy Hanks while the GM&O glorified the confederacy. In this case, the South won the battle.